EDGE,

Barbara Ungar

Ethel

Zine & Micro Press, 2020

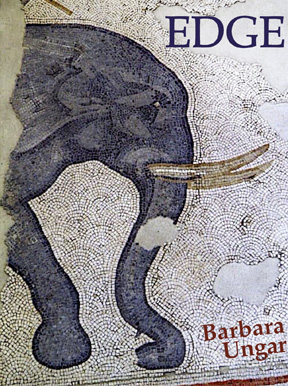

Barbara Ungar’s EDGE, a handsome chapbook with the image of a deteriorating 6th century elephant mosaic sewn to its front cover, telegraphs its themes pretty immediately: the fading of Earth’s species, the devastating environmental impacts humans are causing and witnessing. The title points to the EDGE (Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered) list while also highlighting our precarious position. Ungar’s poems take us from “the deepest bellies // of lantern fish” (8) to “a captive breeding program in a trailer” in Hawaii (31) to “the tourist trail” in “Myanmar, still Burma / then” (19), all the while sharing observations and facts about the animals, insects, birds, or fish who live there, or used to.

The opening poem “As If” lays out the problem at the heart of EDGE: “We cannot even count the ants / or name the animals / before we wipe them out” (7). This is a sad and disturbing proclamation, to be sure. In some ways, though, the poems in this chapbook do the work of offsetting this claim; Ungar includes an impressive variety of animals—ants, penguins, seahorses, dragonfish, fruit flies, moths, caterpillars, sharks, turtles, spiders, jaguars, polar bears, hummingbirds, snails, jellyfish, octopuses, among others—in these pages. While Ungar doesn’t count the animals per se, she does often name them, including italicized Latin terms beneath her poems’ titles. The poem “Godzilla Vs. Nomura,” for example, includes the parenthetical “(Nemopilema nomurai)” so interested readers can google and learn more about the particular jellyfish “swarming beaches” and “clogging nuclear reactors” and “wiping out sturgeon” (36). Ungar also conveys factual information about Nemopilema nomurai in her poem, poetically of course: they “grow from a grain of rice to the size / of a washing machine in six months” (36).

As often as Ungar reminds us that “Owls are all but gone from Arizona” (20) or how “Half Earth’s creatures / have vanished in the last half century” (28), she avoids offering a lecture, or making readers feel condescended to. Instead, the poet tends to point out peculiarities, inconsistencies, oddities, and entertaining facts about animals. While we may be helpless to stop the environmental failures already occurred, Ungar’s poems invite us to know more about what is happening now, and to learn about the species being affected. When the Minute Leaf Chameleon (Brookesia Minima) is in danger, it’ll “drop to leaf / litter and play dead / twig” (10). Blue whale “[c]alves guzzle 1000 gallons / of milk, gain 200 pounds a day” (15). The Bumblebee Bat has “thumbs with claws / & uropatagium, webbed hind legs” (18). And “jaguars / can bite through skulls” (22).

The knowledge Ungar offers is not merely about the animals in question; some poems helpfully trace background information to inform readers why these species are threatened or threatening. “China’s runoff causes blooms / of giant pink Nomura’s jellyfish,” (36), she points out in “Godzilla vs. Nomura.” Ungar reveals that the “Madagascan Moon Moth” is a victim of multiple types of capitalism. It’s been “[e]ndangered by slash and burn,” and “[y]ou can buy / their eggs online (ten for twenty pounds) / their exquisite corpses, framed” (12). Knowing the causes of habitat or species loss might encourage us to find our own ways, however small, to help stop future damage. By reading these poems, we accumulate pieces of knowledge and understanding that allow us some agency in the face of climate grief.

The twenty-four poems collected here are not all sadness and inditement. The creatures in Ungar’s poems are often described by subtle ironies, even in the face of extinction. In “Lonesomest George,” a poem that considers the last of the Achatinella apexfulva, George the snail “ended his days / alone” in a breeding lab called “the love shack” (31). A similar dry wit pervades “Average Monkey,” a poem focusing more on humans than animals. Ungar writes,

When

my father began to hallucinate,

he

saw heads in the dishwasher and the cupboards

I

know they aren’t real he said

but

sometimes I wonder what they like to eat

Like the other species mentioned in EDGE, the human in the poem (“my father”) is deteriorating; also surprising is how the imagined humans (“heads in the dishwasher”) in the poem aren’t passive; even they are consumers who “like to eat.”

The poet’s attention to language continually keeps readers engaged. Ungar’s taut line breaks may describe “the ever / shrinking ever // green rain / forest” (11), but as her short lines narrow they also create sonic pleasure: habitat is “shrinking,” but the end words that emphasize “ever” “ever” “forest” create an almost-hopeful optimism that rings in our ears after we’ve turned the page. In “Rhinochimaera,” the poet lists varieties like “spearnose / paddlenose straightnose knifenose” (33) to describe varieties of cartilaginous fish, allowing readers to linger in the pleasure and strangeness of language and image; she further describes these “marine monsters” as looking “like // the lovechild of Dumbo and a shark” (33). Some of my favorite moments are when the poet brings the self into the poem; through Ungar’s first person narrator readers experience moments of emotional connection. “I was in a torpor too” (19), the speaker acknowledges, or “I felt the cat / I shit you not / hunkered in her fur” (29). EDGE is a compelling read all around. This short collection is particularly notable for its crucial subject matter, its even-handed approach, and its grounding in science and contemporary culture. But it’s Ungar’s masterful wielding of material that makes EDGE so pleasurable. We want to read these poems, and—importantly—we then want to return to this chapbook and to read these poems again.

Genevieve Kaplan is the author of (aviary) (Veliz Books, 2020), In the ice house (Red Hen, 2011), and four chapbooks, most recently I exit the hallway and turn right (above/ground 2020). Her poems have recently appeared in or are forthcoming from Bennington Review, Posit, TinFish, and The Second Factory. She lives in southern California where she edits the Toad Press International chapbook series, publishing contemporary translations of poetry and prose. More at https://genevievekaplan.com/