Beast Body Epic, Amanda Earl

AngelHouse Press, 2023

Listeners of The Small Machine Talks, which has been Amanda Earl’s solo podcast for some time now, will have heard mentions of her near-death experience. As part of discussions with poets and poetry-adjacent artists, these mentions act as devices to connect with her interlocutors or to push the exchange into more vulnerable territory through a mutual openness. Made with humour and honesty, never seeking pity or attention, they are devoid any sense of drama. They open up moments of humanity.

Some months ago now, Earl shared that she had completed a manuscript about this near-death experience and that, unable to find the right publisher for it, she would publish it herself, through her AngelHouse Press. A small press, along with the printing tools and expertise of Coach House Press, seemed like the best way to share the long poem and maintain its vispo components. By now, poetry enthusiasts around Ottawa should have had the occasion to run into Earl and purchase a copy from her.

I also received my copy from her hands. There is so much in that gesture: she hands over the book, her hands are alive, they wrote the words, they carried them to the reader. An intimacy, an occasion to run one’s fingers where her fingers have been, and then to retrace a series of days, to walk through a loss that, thankfully, was far from complete. But there is a loss, even though Earl is incredibly herself. There is sadness and fear and doubt in her whimsy, but the whimsy is there, and her smile is full, unencumbered. Her voice as hesitant as ever, grasping and groping for a way toward what hadn’t yet been said; Earl is not one to polish pages until the writer’s struggle can no longer be perceived. There are asperities for the readers’ fingers to enjoy.

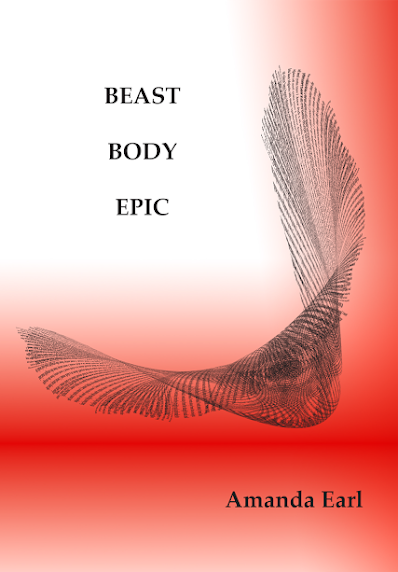

Is the third section the best drug sequence written in recent memory? Does it change anything that the drugs were hospital drugs, that it might have been ICU psychosis, that the improbable dream-like events actually happened to Earl (though the modality in which they happened remains to be established)? This section rises above the others in its scope and breath and in the sense of reality it creates (and the other sections are already solid and almost (almost!) too real). Here the poem folds upon itself, takes on the feather-like lightness of the visual poem on the cover, the reversibility of events in dreams, and the disheveled existence of the patient:

Earl uses the possibilities opened by the well-spaced prose poem to slide into ambiguous beauties: “I lay in the dark when cracks opened let myself be swallowed up taken to who knows where no pomegranate seeds just blood overflowing the banks of an unknown river.” Or – it’s ok, it’s blood. There are such strong phrases here: “Ached green in the damp,” “ethereal demoiselle,” “sky-blue line of crows.”

In previous sections we have the sheer – sheer, as in a thin, veil-like covering for what is truly happening –, sheer panic of the displacement toward the hospital, the pre-operatory helplessness, and then the confusion and high-pitched whine of pain that follow the operation. These sections must be read as each forming a whole to have their full effect: a steady slip into uncertainty and disorientation. The following sections also each take on their own personality; the same poem unfolds, but its form shifts as the body does. They include something of a letter; a list poem that is also a chronology; and short and small blocks of prose poems.

In the fourth section Earl gives us a form of anger that is born of pain and helplessness. She offers grand similes and metaphors – pain “like strike of match against fingernail,” “hell-paint on my insides” – as words and themes circle around, much like pain, sleep, and thoughts do during a fever. Here it seems that rather than being tested by her unbearable condition, she tests her own resolve, down to her commitment to whimsy. We do not get tension, but a furious whimsy, a deepening of images and a shifting of associations that won’t coalesce once and for all and so never gets comical or inspiring. The ever-shifting metaphorical register is a record of what ought to be unspeakable, what is said to be beyond words and evaluation, of moments when the body and the mind, feeling and expression, cannot possibly correspond to one another.

This relationship between mind, body, and self nourishes the fifth section, which explores the intertwining of sex and death. She confronts her continued capacity to provoke lust in others and her marked body’s capacity to stop the abandonment to lust. There is no performative word for how Earl lets us see this great tension: not flaunting, nor unveiling; not displaying, nor exhibiting. She avoids the sentimentality proper to a slow undressing as well as the bravado of a reality brought into plain sight. By identifying herself with Cixous’ laughing Medusa, by using straightforward speech and metaphors from daily life, she opens the possibility of a communion that rejects the mystical and mystification. She opens her reader to a direct look at the kind of life that is possible after wearing death’s clothes for a short while.

Digging into the epic form that carries the poem, Earl opens each section with a quotation from ancient mythology or from its criticism and critique. She keeps that corpus alive and, with it, the epic form – just as criticism and critique do, leaving it better able to do its work by helping it survive its crises – and if it leaves scars and trauma, so be it. She imprints the seal of indeterminate meaningfulness upon the epic tradition by cutting these quotations from their context and neighbourly words. She brings it into movement by weaving the quotations into visual poems that evoke the manner in which they float within collective consciousness. She openly rejects the unity of any work or word by taking on their literal reshaping.

The visual poem that opens Section VI, based on Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette, evokes the act of speaking by practicing an opening in the middle of the text, in what can be read as the outline of a head and shoulders (and a hat, because there’s a hermeneutics of visual poetry that borrows from the hermeneutics of clouds, and because that’s whimsical too). In this sixth section, Earl reconstructs the act of writing poetry based on lived moments by narrating the moments ahead of presenting a versified poem. Each poem thus includes its own preface, which is just as much a part of the poem as what might be read more immediately as a poem. Italicized for separation and distance, it displays the lack of a hinge, the uncertainty of the connection between experiences and their telling, the difficulty of placing experience on the side of narration and of poetry.

Earl thus destroys part of the epic poem, and notably its obsessive repetition of form, in order to make it do new, better things. She becomes the metaphor for her poetic work, reattaches the narrative form together but leaves the seams visible. The book bears the marks of the effort, of the reconstruction, of the reassignment of tasks it performs, and which Earl has had no choice but to perform herself through her illness. The poem is tentative in a lovely way, and then self-assured. Over and over. Brutal, soft, without a sense that everything is ok. There is no perfect reunification with oneself: “Grief is still there. Guilt is still there. I left her on the bed, my counterpart. She is in ICU and dying. I floated out of her and yes, there is a doubling. I feel her silence. I fill oblivion white sheets with colour.” There is no perfect coming together with others (more die, or pass through the poet’s life). The visual parts of the poem evoke heaviness and closeness at first, a lack of control. They become more and more open, free, self-reliant, anchored. But they are not whole; the strength comes with weakness, and the recovery and newfound health work themselves through aging. Things do not become entirely better – they become different as the adaptation takes place. The recourse to mythology in the opening quotations leave room for a meditation on dying, on the return of threats to life, and the last poem recounts the entirety of the events, and more – a third way to live what has been lived and written about already, and what will continue to be lived through at each new stay in the hospital.

Jérôme Melançon writes and teaches and writes and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His third chapbook, Bridges Under the Water, was published by above/ground press in August 2023. It follows Tomorrow’s Going to Be Bright (2022) and Coup (2020), as well as his most recent poetry collection, En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He has also published two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016), as well as one book of philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018). He has edited books and journal issues, and keeps publishing academic articles that have nothing to do with any of this. He’s on various social media, with handles resembling @lethejerome.