Say It Again: An

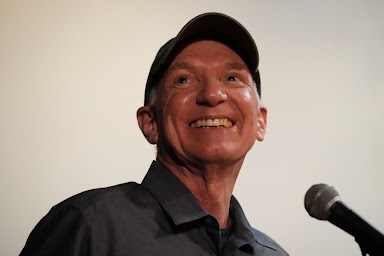

Autobiography in Sonnets: An Autobiography in Sonnets, Volume One: The Road Goes Away (the first thirty years) 1942-1972, Michael Lally

Beltway Editions, 2023

One of the many pleasures of reading Michael Lally’s Say It Again, the autobiography of his first thirty years written entirely in sonnets, is meeting up with an incredible cast of characters. There are wild lovers, eccentric family members, jazz musicians, famous and not-so-famous poets, and other folks who are just plain freaks. One of my favorites is Billy, someone the author comes across in the early 60s who is a Duncan Yo-Yo salesman. His spouse, Sandy, has invited the poet over to their “pad” for a little romance (he is unaware she is married). As it all gets going, you find out that Billy is lurking in the background, and, as they say, “likes to watch.” Over breakfast the next morning, the couple tells the poet they have an open marriage and believe in free love—an arrangement no doubt considered rather avant-garde during this era. The poet’s pretending to be hip to all this adds a comic touch to the scene, and then, things get a little wackier as Lally and Billy begin to work together:

Billy works for Duncan yo-yos traveling the

country showcasing his yo-yo skills with the

usual tricks and a few spectacular ones of his

own. At parties he uses two yo-yos and their

strings to illustrate unique sexual scenarios or

he leans a quarter from the top of my ear to

the side of my head, then flicks the quarter off

with his yo-yo, not touching my ear or my hair.

He hires me as part of his stage act, playing

piano behind his tricks, ending with the coin

on my ear bit. He’s handsome in the manner

of old movie stars, with slicked-back dark hair,

smoky eyes, and the wisp of a smile exuding

confidence and some secret deviltry going on. (128)

This concise portrait illustrates the advantage of telling your life story in sonnets. Characters, incidents, and scenes take on an almost cinematic quality—each tightly edited to avoid the boring over-description one often gets in prose. I can imagine a young Christopher Walken playing Billy in some arthouse indie flick. But more than just entertaining, I think there is an ethical logic that inspires such portrayals. The vivid scenes and characters that flash by in the something like 450 sonnets create an alternate culture—one snuffed out by the world from which they are drawn. We find out later in the sequence that Billy and Sandy, busted on trumped-up “morals” and drug charges in connection with the coffee house they run (“a beatnik nuisance”), end up doing time. Billy, in fact, spends a year in solitary confinement. (138)

Lally has commented that “The few movies and books and plays and songs I knew that addressed the world of my family, often used…stereotypes, but never reflected my experience of who these people really were…” (Kimmelman). I think Say It Again extends the wish to “get it right” to all the people and scenes he encountered on his journey to become a poet. As a result, more than a self-portrait, the book is a chronicle of the times, a sort of “history from below” of the birth of what became known as the counterculture. Within these pages you’ll discover everything from how the three-quarter overcoat was a style invented by Puerto Rican street gangs “running from the bulls,” (69) to the impact of the early Beatles on local jazz scenes (159), to telling examples of the how political speech gets manipulated by media. (199)

Lally was in an excellent position to witness

such cultural history, as Say It Again, volume one of his autobiography,

covers the years 1942-72. His life is an odyssey from working-class South

Orange, New Jersey roots, to a life as jazz musician in the Village, to a stint

in the Air Force, where he was stationed in cities across the country. The

book’s last third, covering the mid 60s to early 70s, is comprised of sonnets

written about attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop on the GI Bill, starting a

poetry scene in Washington DC, and then hanging out again in NYC.

The inspiration he gained through witnessing the changes in the culture and

himself gave birth to a major poetic career. Lally became a key figure of the

New York School’s second generation, and in my eyes, is the literary godfather

of many poetries, ranging from performance to punk. He is also the subject of a

documentary currently in production. The cinematic quality of the sonnets

perhaps hints at his later career, when he worked as both actor and script writer

in the movie industry. Say It Again (Beltway Editions) along with Another

Way to Play, Poems 1960-2017 (Seven Stories Press), offer an excellent

introduction to his work.

The story behind his decision to write a life in sonnets reveals the project’s

animating impulse. During the “Iowa”

section of the book, Lally relates how poet (and later renowned art critic)

Peter Schjeldahl did a reading in which he recounted his daily life during a

stay in Paris in the form of sonnets. From this, Lally got the idea to “distill

the pages of prose on my early life/into twenty fourteen-liners I call THE

SOUTH/ORANGE SONNETS, supporting my belief/that my own life is just

as important as any/world traveler’s.” (227)

The sonnets, then, are not only a “distillation” of the poet’s journals, but might

be seen as a translation of the “Parisian” sonnets into a different life and

idiom— modulating the stylistic key from urbane to urban. The result is a streetwise

poetics that defines for itself how the rhythm and music of a sonnet should

work. Here is Sonnet #17 from the book’s “South Orange” section:

There is some

music you have to listen to.

In South Orange there were rich Catholics

rich Protestants and rich Jews. My cousin

became a cop. His brother was stabbed by

an Italian called Lemon Drop. Across the

street lived two brothers called Loaf and

Half a Loaf. My brother became a cop. On

St. Patrick’s Day 1958 I came home drunk. My

mother said He’s only fifteen. My father:

It had to happen once. My grandfather was

a cop. One cousin won a beauty contest at

thirteen. My sister married a cop. By 1959

I knew I was going to be a jazz musician.

My father joined AA before I was even born. (33)

A glance at this sonnet reveals some of the marks of Lally’s style: sneaky internal

on and off rhymes (so you hear the echoes, without knowing exactly where they come

from), staccato sentences and quick flashing events, repeating words and phrases

that pepper the rhythm with swagger. And though not every sonnet carries all these

traits, there’s an overriding feature here that appears again and again: this

is a social poetry, a poetry as much about life in public as in private,

a poetry of names. The writing shares this quality with other art forms

that portray subcultures. Think of the lyrics of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild

Side,” introducing listeners to Candy, Little Joe and Holly; Kerouac’s Sal

Paradise and Carlo Marx (to name a few); or that scene early on in Scorsese’s Goodfellas,

where you meet Jimmy Two-times, Frankie Carbone, Sally Balls, Freddie

No-nose, Nicky Eyes, and the rest of the crew.

In Lally’s sonnets, this poetry of names is extended from people to places; you

meet Bambi, Destiny, Cliff, Dewit, the Harlem beauty Theresa, along with Dylan

and Ginsberg, at places such as THE FAT BLACK PUSSY CAT, OBIES, PRIDE’S

CASTLE. And then, later, there are cameos of writers who were to become

poetry “names”: Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Anselm Hollo, Lewis MacAdams, Terence

Winch, Diane Wakoski, Ray DiPalma and others. I think of the book as a sort of subcultural

pastoral, where nymphs, satyrs, flora and fauna, are replaced by underground

celebrities, hangouts and cultural hotspots.

Throughout this collection, such characters tend to bounce into each other,

much as their names do, in the tight spaces of the sonnets. This helps create

the cadence of the writing and in doing so, mirrors a characteristic of Lally’s

world: no one wants to stay in their (socially) “assigned” places. Ethnicities,

cultural styles, and sexualities, not only rub shoulders but rub off on each

other, changing mores, widening visions.

All of which is to say the mini worlds of the sonnets are places of porous

borders. There are racial crossings: the earlier sonnets, the age of the

so-called “White Negro,” feature numerous interracial love affairs, at a time

when this was a dangerous way to love. The poet’s urban roots, career as a jazz

pianist (not to mention his stint in the Air Force), lead to what might have

been considered at the time a kind of interracial trespassing. And there is not

only interaction, but metamorphosis. The author transforms from alcoholic to

sober to drug user, from macho to feminist, jazz musician to poet, vet to political

activist, straight to bi. His cast of characters shifts shapes along with him.

One of my personal favorites is an activist named “Mike J.” The son of a Broadway

producer, “Mike fell in love/with Chicago, its working class and poor,/while he

was on a football scholarship to Lake/Forest and dedicated his life to helping

them.” (213) A few sonnets later, we see a character reconstructed along both

ideologic and stylistic lines, one whose fluid class identity helps serve the movement:

Mike J slicks

his blonde hair back greaser style,

as they call it in Chicago, wears a three-

quarter length black leather coat, same as my

own. Known as an SDS leader nationally, after

LIFE did a story on him, he has an idea for

organizing Chicago’s white gang kids into a

radical street organization and wants me to join

him. We begin spending more time in Chicago

and discover he not only runs with the Black

Panthers, and white street gangs, and sons of

hillbilly immigrants from the South, but also

moves with ease among the liberal elite of the

city, raising money and backers for the cause…(217)

Looking at the variety of racial, sexual, ethnic, and class identities, not to mention the cultural idiosyncrasies of culture styles, the choice of the single form of the sonnet to house it all becomes particularly interesting. As I’ve mentioned, the tight editing involved helps these stories move briskly, so much so that I found myself wishing all memoirs were written in taut poetic forms. But in addition to pacing there is, as I hinted at earlier, an ethical advantage.

These sonnets, however internally

modified, keep to their classical fourteen lines. As such, the form forces the

author to decide what counts. As mentioned, interactions with major

media in the sonnets show how words get put in the mouths of the speakers, and

how cultural particularity gets distorted when framed in clichés. I read the

sonnets as a way of setting the record straight, as if to say: “no, look here,

this is what’s important.” Add to this

the fact that the poetry, as a genre, is often seen as an art form that just

doesn’t count, and you can interpret the sonnets as a way of insisting on the

importance of people, events movements and even forms of creativity that are

ignored or forgotten by the culture at

large.

There’s also the fact that the sonnet itself is a somewhat universal form, at

least for the Western canon. It’s interesting to note that the saints of

universality who populate these poems all meet with assassination. There are

sonnets dedicated to Malcom X (killed when he began to explore cross-cultural

alliances (203), Fred Hampton (“the/young charismatic,

coalition-building-with-poor-and-working-class whites, Chicago Black/Panther

leader I’ve met and admire”) (237), and, of course, Martin Luther King, who…

spent years

fighting racism and despite attempts

on his life and tons of threats seemed invulner-

able, but as soon as he organized a poor people’s

campaign talking about the haves and the have-nots,

BAM! I wonder if the Marxists have it right. (203)

Though no doubt beyond

the author’s intention, in retrospect, it’s hard not to read the insistence of

the sonnet form as the one that houses the many, as perhaps a

micro version of a utopian wish for a unified movement toward true democracy.

In any case, the sheer utopian joy of metamorphosis in the sonnets is exactly

the type of pleasure now under suspicion in our times. US politics and culture

seem still fighting a war over the social liberation movements of the 60s and

70s. The great delight these sonnets offer, though, suggests no matter the

rhetoric and repressions of our current time, it may be impossible to force the

genii of the freedoms represented here back into their restrictive bottle. We

need these sonnets now, more than ever, to remind us of not just the tragedies

that won these freedoms, but the joy that inspired them.

Notes:

Burt Kimmelman, “The

Crowd Inside Me.” Interview with Michael Lally. Jacket 2. August 29,

2011. https://jacket2.org/interviews/crowd-inside-me