ALFRED

JARRY

You

can thank Roger Shattuck for including him in The Banquet Years, because

it was there that I learned about Alfred Jarry’s apartment at 7 Rue Cassette,

in the Sixth, an apartment known for one extremely odd feature.

I

parked my mobylette on the street and rang a bell. When the concierge answered,

I explained to her that I was interested in confirming that Jarry had lived here,

and what’s more, in an odd apartment. She’d never heard of Alfred Jarry, but

knew about an eccentric apartment. She reached for a phone, dialed, said a few

words, and soon a man who worked at the building appeared.

“Follow

me,” he said.

We

climbed a few floors, then he found the right key and opened an apartment door.

“Watch your head,” he said.

We

entered, and, as advertised by Shattuck and Apollinaire, the ceilings were at

best five feet high. We had to stoop to enter and remain stooped to stay. With

just a few rooms, the man explained to me that years ago the owner of the

building thought the ceiling too high, and had lowered it. One reason was, more

things could be stored there, and in the altered space above, and maybe more

rent could be generated with the rooms done that way?

Apparently,

Jarry didn’t mind the lowered ceilings as he was, for a writer concerned with

royalty, a short man. Shattuck wrote that Jarry’s head just rubbed against the

ceiling, “And he collected the flaky plaster like a severe case of dandruff.”

Apollinaire,

in his account of visiting the room, noticed that rather than a bed, there was

a pallet on the floor. He wrote, “Jarry said that low beds were coming back

into fashion. The writing table was the reduction of a table, for Jarry wrote

flat on his stomach on the floor.”

A

few books, his portrait by Rousseau, and an enlarged stone phallus were all the

things the poet noticed.

The

rooms were all but empty in 1973, the year I visited.

GERTRUDE

STEIN

It

was only twenty-seven years after she died that I knocked on her door in Paris.

Everyone knew where she’d lived in the 6th Arrondissement, at 27 Rue de

Fleurus. I walked to her street, found the number, and knocked. What I didn’t

know was, she hadn’t lived in the building that lined the street. You got to

her celebrated studio by walking through a corridor to a building in back. This

passageway was patrolled by a concierge who pointed the way to Stein’s door,

twenty-five feet across a courtyard. Quiet back there, far from the street, I

knocked on the door. After a few seconds, a woman opened it with inquisitive

eyes. It wasn’t Alice B. Toklas or Gertrude herself or even Hemingway or

Picasso or Juan Gris or Sherwood Anderson looking at me.

It

was the current inhabitant. After the pleasantries of “Bonjour,” I explained

that I was reading Gertrude Stein, knew she’d lived here for years, and just

wanted to see the place. And to my surprise, the kind lady said, Well, come in,

and have a look. The door led directly into the big room in which Stein wrote,

and whose walls had been covered by paintings she’d collected. But nothing now

resembled the fabled photos of Stein sitting in that room with works by

Cézanne, Picasso, and Henri Matisse, et al., even if the space was the same.

Polite furniture turned the studio from salon to bourgeois living room. The few

paintings on the walls were generic, but the woman who now lived there couldn’t

have been nicer.

Writing

can take place anywhere, at any time of day. Gertrude was known to write by

hand at night, then pass her chicken scratchings to Alice in the morning, to be

typed up. It was enough for me to see the room, get a feel for its dimensions,

notice the beige walls, the wainscotting, the rug on the floor. I thanked the

lady for letting me in.

“You

live in a marvelous place where important adventures in writing happened years

ago,” I said, in French, though I was pretty sure she knew that already. “Your

kindness means a lot.”

As

I turned to go, she followed me to the door.

“Merci,

madam. Au revoir.”

John

Baldessari : Waving Goodbye

What

would make the tallest artist in the world think to have a camera set up behind

him as he stood at a channel connecting a bay to the open sea? And why would

the artist stand there, all six-feet seven of him, waving goodbye to any boat

moving through the channel? John didn’t know anyone on those boats. He had no

business being there.

Protected

in the bay, tied up, sailboats of all kinds bobbed gently. And through the

channel, not far away at all, as big as a dream, was the Pacific Ocean.

Baldessari’s idea was to film boats leaving the bay, motoring slowly through

the channel. As the boats passed him and camera, he would stand there like a

fool waving goodbye to them.

John

wasn’t a sailor, though he grew up in a Navy town. Surely there was some hidden

meaning to this ridiculous gesture, but what was it?

With

the camera stationary, the boats moved slowly from right to left. And John,

standing between the blue water in the channel and the camera-- unseen by

anyone in the boats--kept waving goodbye as they passed. How odd, how out of

the blue appeared this gesture, whatever the reason. And to think that a mere

six years earlier the artist was still making big abstract paintings.

Speaking

of which, I’d seen a show of these abstract paintings in San Diego in the

mid-sixties, at the Art Works Gallery on Adams Avenue. What was memorable about

that show was the fact that each of the big paintings had a dramatic black X

painted on its busy surface, as if to cancel everything in it. They weren’t bad

paintings; they just weren’t anything but paintings.

Later

we’d all learn that John took those “X-Sign” works and other old paintings to a

crematorium and had them burned. Done with painting as he’d inherited it, John

saved the ashes from his life’s work to date and deposited a portion of them in

an urn. Then he had a bronze plaque fabricated in the style of a grave marker

that recorded his full name and the dates “May 1953” and “March 1966”—thereby

putting to rest the early, pre-breakthrough phase of his career.

“The

Cremation Project,” dated 1970, became one centerpiece in the conceptual shift

from a studio based practice to a post-studio way of working. He would not

paint again, nor make, as he repeated over and over in a hand-written page, any

more boring art. That statement, filling the page, was made by John the

school-kid, punishing himself for accepting the conventional role of painter.

Like

some Fluxus artists before him, John was conversant with MARCEL DUCHAMP, Robert

Lebel’s influential monograph on the French-American artist, published in 1959.

And, from his own generation, he was well aware of Sol LeWitt’s early

idea-driven conceptual pronouncements. In fact, one of Baldessari’s terrific

early works was a film of him singing LeWitt’s conceptual sayings.

Suddenly

the idea game was on, and it didn’t require canvas, gesso, brushes or paint.

Thus began the work that made Baldessari’s name. Brave enough to risk calling

what he made art no matter the conceptual brain spasms that generated it, a

post-studio way of thinking about what Art could be took over.

Like

the very early deadpan video work of William Wegman, made in Venice, CA in the

early 70s, Baldessari’s short films from the same period are filled with poetic

inspiration, art smarts, and throwaway charm. I wonder if these artists had met

yet? By 1973 they were both showing at Sonnabend Gallery in New York and Paris.

In one color film John repeatedly tosses three orange balls in the air and

photographs them just as they are about to fall back to earth, trying to

capture the orange balls making the shape of a triangle against a blue sky.

With four balls, in another flick, he tries to photograph the tossed balls in

the air as they approximate the shape of a square. It doesn’t matter that a

perfect triangle or square is never caught. It is enough to get close. A

viewer’s judgment is part of the experience. Does the effort succeed, or fail?

The daft thinking redeems the effort, or vice versa. And in another little

known two minute movie shot in autumn, he has himself filmed standing below a

tree picking up its fallen leaves and throwing them back up into the branches.

The film isn’t about futility, or failure, though. Nor about time passing. But

what is it about?

Gallerists

had no idea how to sell these two and three minute Super-8 films. Bundled in

threes? Editions of 25? And how long would they last, if played often? As much

as anything, a collector would be buying synapses of a brain working at a

serious remove from the old paradigm.

We

walk into the Dome, in Montparnasse, get a table, and order Courvoisier. A

famous cafe is the perfect backdrop in which to talk about this new thinking.

John says the art world is way more fun than the literary or academic world.

Not only is there more curiosity, and more risk, there are more drinks. A

generation of Post-Pop artists is beginning to think in new ways. And, as

galleries in Europe and the States begin to be aware, there’s a growing

quantity of wall space upon which to document the new, to educate the populace.

John is 42 years old. He is teaching at Cal Arts, no longer at a college in

remote, unheralded National City (near the Mexican border). He reads

everything. He likes people. And he likes to laugh. There is no end of things

to think about. Of new ways to make language and photography and film embody

fresh meaning, amusing sport.

A

year later I invite John to do the cover of Stooge #11, a poetry

magazine I edit with Laura Chester. In no-time he provides a two panel

photographic work (front and back cover). Derived from an early series about

choosing from like-minded things, John has arrayed three walnuts on the front,

and three on the back. Nearly indistinguishable from each other as things

(their crenellated surfaces resemble brains), the finger of the artist points

at the top walnut on the front cover, as if declaring it the one. Turning the

mag over, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the walnut at the bottom, which has been

moved slightly aside to reveal the name of the magazine, “Stooge,” printed in

pencil. Clearly, the finger has not chosen the “right” walnut, the one

concealing the mag’s name. But what if John is thinking, do you really want to

pick the right stooge?

McQueen,

Chamberlain, Monk

It

was not what McQueen was wearing, it was how he talked.

Ticket

in hand, I stood in line waiting to enter the Monterey Jazz Festival on a late

afternoon in early September, 1964. Standing behind me was a woman with

chestnut-colored hair, and behind her, with his date, looking exactly like

himself, was TV & film star Steve McQueen. Seems that this fictional Josh

Randall, of “Wanted Dead or Alive” fame, after 93 episodes on TV and a role in

“The Magnificent Seven” in 1960, and his date, were surprised that they knew

the woman standing in front of them. They began to exchange small-talk,

starting with the surprise of being there at the same time. Then Steve asked

her, “You got your admission, baby”? So effortlessly hip was his sound—the

exemplar of cool, the avatar of anti-hero ease--that it should be spelled, “You

gotcher ‘mission, babe?” The woman was the same height, same age, and same hair

color as his date. The two women could have been sisters.

“Yes,”

she said, lifting her left hand, showing him a ticket.

Aware

of me looking at him and listening, Steve’s eyes, missing nothing, stayed

focused on the two women.

Over

a beige checked shirt he was wearing a light jacket. The cut of his hair, never

long, never short, fit his fair head perfectly.

Once

inside the gate, I wandered forward, passing a grandstand on the right, filling

with fans, and on the left a sea of chairs arrayed in the middle of a vast

outdoor setting. At one end of the grandstand, standing not just tall but very

tall, was Wilt Chamberlain. Did he like or dislike his nickname “The Stilt”? He

looked out over the scene like a sentinel, clearly waiting for someone to join

him.

And

then, for a second, he looked down at me. And I looked up at him. I couldn’t

help but smile. I was wearing pants cut off at the knees. And Wilt was wearing

short pants too! Not the kind he wore on the basketball court, but not slacks,

either. My cut-offs were cast-offs; Wilt’s were tailored to fit his

extraordinary seven foot two inch tall body. With hair cut short, and quiet

eyes, his arms seemed to hang from his broad shoulders as if from somewhere

north of the Canadian border, only to appear, finally, half-way down the coast

of California as beautiful hands, doing nothing but standing there at a Jazz

Festival.

I

thought of Wilt dunking with ease, of his scoring 100 points in one game, and

of his many defensive battles with Celtic Bill Russell. I remembered Wilt

missing free throws. And reading about the mirror on his bedroom ceiling, and

of this bachelor’s legendary accumulation of lovers. Covering his legs, up to a

point just below his knees, the Stilt sported expensive beige socks.

I

wanted to get closer to the stage, so walked farther down an aisle, finally

finding a seat in the middle. Next up on stage was none other than the

Thelonious Monk Quartet. There were other groups that evening, no less on the

bill than Monk, but I don’t remember them.

Thelonious

hadn’t yet appeared on the cover of Time magazine, but would soon. I

knew the songs, sometimes by name, but always by Monk’s legendary time and

accents. At one point deep into his set, while Charlie Rouse was taking a long

tenor solo, Monk got up and started dancing, spinning trance-like around the

stage in perfect time to the rhythm and feel in Rouse’s solo. It was something

Monk did for a while, this dancing on stage, until not long after Monterey,

when the Time article appeared in print, making particular mention of

the pianist’s free-spirited Terpsichorean thing. Only then did Monk stop doing

it.

Rouse

is winding down, playing the last measures of his solo, Monk’s still spinning

like a dervish in the middle of the stage. Where is he? Will he come back? His

arms are flying, his feet are free. Then just as Rouse plays his last note,

Monk bolts toward the piano, and while still upright, hits a flat-fingered

chord with both hands in the exact perfect groove, a split-second before his

body slides onto the piano bench and the beat goes on.

The

word “timing” is not strong enough to account for the dramatic effect of that

chord, of Monk’s body in space, of that slide on the bench, of the hat still on

his head. Of the audible gasps and serious applause that followed.

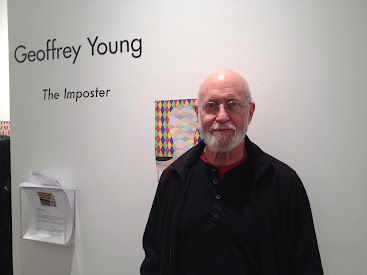

Geoffrey Young

has lived in Great Barrington, Massachusetts since 1982. From 1992 til 2018 he

presented hundreds of shows of contemporary art at the Geoffrey Young Gallery.

His small press, The Figures (1975-2005), published more than 135 books of

poetry, art writing, and fiction. Recent chapbooks of his poetry, prose and

colored pencil drawings include Thirty-Three (above/ground press, 2017),

DATES, ASIDES, and PIVOT. Young has written catalog essays

for a baker’s dozen of artists.