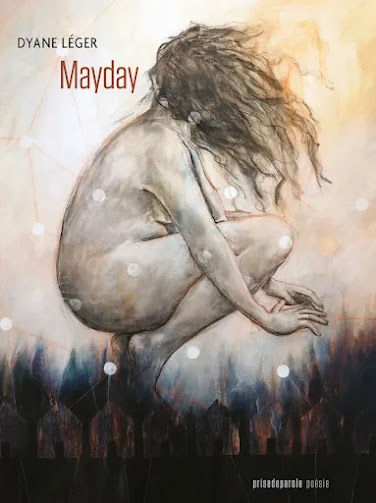

Mayday, Dyane Léger

Prise de

parole, 2023

With Mayday, Dyane Léger wrote a book that might just be the Acadian Second Sex. The first woman to publish a book of poetry in Acadie (in 1980 – the second being Rose Després), Léger relies on the mixing of languages that constantly occurs in Acadian speech and on the description of women’s experiences. The result is a book-length story in verse that presents clear emotions and states of mind while eluding the naming of events and people. By focusing on an unnamed woman as the main character of the story, Léger is able to confront social forces and structures as Mam’zelle experiences and resists them.

It would be false to say that the book is written in one language. In creating her narrator, Léger turns to the person who speaks rather to her languages, and moves between what could be distinguished as French, Chiac, English, Mi’kmaq, and other languages that also slip in, like Gaelic, all of which exist as a single fabric without seams or edges for she who is speaking it. Léger presents a philosophy of language in action here, a refusal to separate, a dwelling in the constant birth of expression. English pronunciation is acknowledged through umlauts (“bräcer,” “Whäm,” “too bäd”), familiar pronunciation through creative spelling – including showing a French pronunciation of English words (see: “de” or “di” for “the”; “sinjoye” for “s’enjoy”). Puns abound throughout, sometimes within French (“ses l’armes” instead of “ses larmes,” transforming tears into weapons), but particularly through the mixing of French and English: “déwrenche” transforms “dérange” (bother) into a de-wrenching, showing Mam’zelle’s great strength. Common expressions are transformed to mark her determination: “No wäy! Oser!” (“No way! Dare!”). We find this inter-linguistic movement of speech within verses such as “right now si tu câres une petite miette about moi.” (26) We also find it in longer passages, which also often feature aspects of this spoken language (like “os” being spoken “ous” and giving us a possibly pluralized “ors”):

Can’t afford to be

anywhere else, really.

So, sadly and

madly,

[the little one],

she’s always on the edge because

[she never knows

when the seven-headed beast will turn right back around

to come collect is

due: the skin she has on her bones.]

Can’t afford to be

anywhere else, really.

So, sadly and

madly,

la petite, she’s

always on the edge because

elle sait jamais quand la bête-à-sept-têtes va ervirer

bäck de bord

pour venir collecter son dû: la peau qu’elle a sur les

ous. (24)

The poetic aspect of the book mostly exists through the rhythm that enjambment and white space create and through the heavy presence of linguistic innovation and transformation and the constant recourse to imagery. While the book is set in verse, much of it reads like a story told in prose poetry. And this story is made all the more tangible by the light but constant presence of popular culture. To limit the non-exhaustive list to music, we move through many lullabies through Whisky in the jar, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Seeger (or Metallica?), Pink Floyd, Janis Joplin, Stevie Nicks, David Bowie, Men without Hats, and The Tragically Hip. Literary figures also play an important role, Gabrielle Roy and Patrice Desbiens among them as non-Québécois Francophones writer who opened up possibilities for writing in French in English surroundings.

The most radically feminist aspect of Mayday is the development of the character’s interiority in relation to events that might inspire pity or scorn – two ways to refuse to recognize her as an equal and to negate her agency. There is nothing normal about Mam’zelle, except for the fact that, like every person, she exists outside of norms and brings them into question simply by living. Her eventually falling into norms or entirely rejecting them then has an effect similar to the second volume of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex: unveiling that thoughts, hesitations, emotions, situations are shared by many women and are not particular to any one woman, are not abnormal aberrations. There is a great potential for recognition here, or learning about past personal struggles, and the blurry figures of the events that Mam’zelle confronts will only help readers recognize them by letting them stand as archetypes present in historically and geographically specific situations.

Solidarity runs through the book, including the poem-within-a-poem Mam’zelle writes and significantly reads out loud about the repression of the Elsipogtog resistance of 2013. In fact, the book displays a transformation of Acadian society and culture by spending very little time on the memory of the Deportation of Acadians, mentioning it quickly without making it into a symbol for personal tragedy, and instead offering several pages on this resistance, including the role of Acadian police officers in the repression. “It felt like we were in a different country,” Léger writes, twice (205).

That the events are recounted in English and their consequences in French is also significant. Not only is this story being told, in person, in the book, in a manner that is open to accountability with Indigenous readers given the choice of the language. What we can learn from the story is specifically aimed at French speakers, who tend to refuse to see themselves as settlers on account of their own relationship to the British Empire. And here too, gender plays a role, through masculinity and what might overturn it: “More and more, I wonder if among this gang of Rambo wannabes, / there’ll be one who’s woman enough to face the machine of death, / [dead-on], bare-handed and without blinking” (“De plus en plus, je me demande si parmi cette bande de wannabe Rambos, / y’en aura un assez femme pour affronter la machine de la mort, / dead-on, nu-mains et sans blinker,” 207).

To focus solely on these elements that make up the book would be unfair to the story that drives it. The narrator is entirely external to the main character, la petite, and later Mam’zelle, who is “cursed with an unquenchable turmoil” (50). The only other clear character is LaVoix (TheVoice), a mysterious presence that both guides and leads astray but ensures that Mam’zelle lives her own life in spite of all that is already set out or determined for her, and often brings conflict into her life. The narrator looks at Mam’zelle with amusement, pride – as if she was looking back on a younger version of herself (which is possible, given the timeline suggested by cultural references), or simply at someone who reminds her of herself. She wants certain outcomes for Mam’zelle, she has hopes for her, and sometimes switches to the first person to emphasize it:

In some fine

kettle of fish, some might say Mam’zelle is asking for it.

That she’s already

gone way past [the limit.]

[That if she keeps

on looking for trouble,

it’ll find her,

bang on! Coming to her defense, I say:

Nay, nay, nay,

Mam’zelle is still far from having reached too far.]

But that’s just me

dropping a loonie or two in the wishing well,

mindfully hoping

[that the canari

still sings sings sings,

that the firedamp

hasn’t already blown up the miners.]

In some fine

kettle of fish, some might say Mam’zelle is asking for it.

That she’s already

gone wäy past la limite.

Que si elle continue à chercher le trouble,

il la trouvera, bäng on ! Me portant à sa défense, je

dis :

Nâni, nâni, nâni, Mam’zelle est encore loin d’avoir

reché trop loin.

But that’s just me

dropping a loonie or two in the wishing well,

mindfully hoping

que le canari chante chante chante toujours,

que le coup de grisou n’a pas encore tué les mineurs. (59-60)

The strong presence of the narrator emphasizes the linearity of the story as a story that is being told. Beginning with a description of a child hardened by abuse who remains open to the natural and symbolic world, the story moves into early sexuality and a teenagehood that slides into motherhood and the traps that (continue to) accompany it. It includes asides on Mam’zelle’s thoughts, including her sadness and grief at the story of Laika which allows Léger to create a knowingly imperfect analogy on the cruelty of men. The story climaxes around a birthday party gone wrong and the possible loss of a child, a climax that is framed by the desire for, and by the writing of, a book of poetry.

Léger wants this book to be understood – and not only because a reader would need a strong understanding of both French and English to catch all it has to offer. Mayday carries a heritage with it, a moment or a series of moments in language and culture, in collective being. She thus includes an imposing glossary, followed by detailed explanations of many of the references. These serve as much to make the book more accessible as to preserve this heritage which, as Léger suggests through the ways she uses it herself, can be taken up in the name of solidarity and social transformation.

Jérôme Melançon writes and teaches and writes and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His third chapbook, Bridges Under the Water (2023), follows Tomorrow’s Going to Be Bright (2022) and Coup (2020), all with above/ground press, as well as his most recent poetry collection, En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He has also published two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016), as well as one book of philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018). He has edited books and journal issues, and keeps publishing academic articles that have much to do with some of this.