“Notes from the Field” with its journalistic association seems a good category for my piece on poet-journalists and poetry of witness. Being a poet myself, Co-director of Toronto’s Art Bar poetry series and a frequent emcee, brings me into contact with poets from Toronto and around the country. I listen to and read a lot of poetry. I was away teaching in Hong Kong for just over 20 years and I have been actively catching up on Canadian poetry and other writing since I re-patriated just before the pandemic. That is the primary way I have learned that many Canadian poets are or have been journalists. Here is a list of those I have met or discovered in other ways. (I am sure there are other poet-journalists who I am not aware of.)

- Alice Major (Edmonton, Alberta )

- Joe Fiorito (Toronto, Ont)

- Marsha Barber (Toronto, Ont)

- Anita Lahey (Ottawa, Ont)

- El Jones (Halifax, N.S)

- Mohammed Moussa

(Turkey /Gaza)

- Rosa Deerchild (Winnipeg, Manitoba)

And there’s me: trained as a journalist although I became an academic—a college and university instructor. I include a poem of witness of my own from my new collection, The Meaning of Leaving, near the end of this piece.

In her 2015 interview with Quill and Quire Canadian poet Emily Pohl Weary shared her thoughts on ‘poetry of witness’:

“We are all observers, in the sense that living is a

process of witnessing. As a writer, I’ve always had an insatiable need to

understand the why of situations that might seem senseless. The first time I

encountered the term was in the work of human-rights activist and poet Carolyn

Forché, whose brave and beautiful collection The Country Between Us inspired me at a critical time.”

It interests me that poetry can be a

kind of witnessing, just as journalism can be. Not all journalists

are advocates, although advocacy journalism is a growing trend in Canada. Some

of the poems I have chosen for this article advocate for a point of view.

With this as my premise I have hunted for one poem of witness by each of the poet-journalists featured here. As I write this during another Canadian summer where our forests and nearby communities are ravaged by wildfire it seems appropriate to start with a timely poem of witness about the fire storm that devastated Fort McMurray, Alberta in May 2016. In her powerful poetry collection, Knife on Snow, poet-journalist Alice Major describes residents’ struggle to escape:

From “A fate for fire”

Ninety

thousand now in flight

through

the choked throat and thick smoke

of that

one road out, walls of fire

on either

hand. Hell-mile, hellscape—

vehicles

draining through a downpour of flame,

raining

embers, the roaring lungs

of flames

fifty feet high. Fire-whirls of dust. …

…

Meanwhile the monster makes its weather.

Perilous

updrafts lift pyrocumulus—

that

cloud-fist, inferno’s club—

into the

air. Arrows flicker

of dry

lightning, but no downpour follows,

no

rain-relief. Only the roil

of Thor’s

thunder thrashing the landscape

with a

hazardous hail, hot ember-seeds

that

sprout new shoots. Fire’s spawn spreads

ever

further into green forest.

And the

long road logjammed

with

crawling trucks, creeping cars.

Drivers

gaze at dropping gauges,

emptying

tanks.

How ironic!

Stranded

for fuel in forest terrain

that

floats on petroleum. This fragile thread—

the one

route out, the one-horsed

engine of

economy— all encircled

by boreal

forest designed to burn.

***

With a deft touch journalist Anita Lahey writes about how the climate crisis is altering our seasons. (She is also co-author of the collaborative graphic-novel-in-verse Fire Monster, co-created with artist Pauline Conley.)

Seasonal Affective Disorder

An altered season’s

having her way

with every shapely

cloud. She’s got all

this stuff to throw at us:

midnight furies, fervour

and floods, white-hot

rends in afternoon skies.

Summer’s never been

so cumulo-

nimbus-charmed.

She blows

through the window, simmering

bodies to a salt broth.

Wouldn’t we

fall over ourselves

to be like that, devastating,

once in our lives?

–from While Supplies Last (Véhicule Press, 2024)

I think many of us are struggling with ecological grief about the fires which regularly rage across Canada’s western forests. Another issue many Canadians are grappling with is homelessness. In our chapbook “Homeless City” poet friend Donna Langevin and I were inspired to write poetry about our encounters with unhoused people we regularly meet in Toronto and Cobourg, Ontario. Former Toronto Star journalist Joe Fiorito has written a whole poetry collection about people living on the streets of Toronto. Here is one poem from that collection:

My Pal Al by Joe Fiorito

To the market once a week

for a week of frozen mini-meals,

a coffee and the paper.

In a puddle of daylight

on white arborite he tore his Star

into long thin strips.

“Nobody reads the news

on my dime.” He was the news

when he came home:

new lock, no key; no microwave,

no plastic fork and spoon, no

coffee pot, no cot.

In a stairwell, blue-eyed, rough,

he said he was – until he was

not – well enough.

-30-

- from City Poems; Exile Editions, 2018

When we discussed which poem Joe would like to share he chose this one based on the death of Al Gosling, who died after being kicked out of public housing for refusing to sign some forms.

***

Marsha Barber, a poet/journalist/professor of journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University, was moved to describe an experience of witness in the following poem set in Israel:

Suicide Bomber —Marsha

Barber

“Suicide Bomb Kills 3 in Bakery in Israel” – The New York Times

Somewhere a young man

the same age as my son

wants to blow me up.

Oblivious,

I apply lipstick, blood red,

the day is filled with hope.

I leave for the market to buy bread:

thick crusted, warm from the oven.

When it happens, I’m thinking how good

a slice will taste after I spread fresh butter

and share it with you.

I note the boy. He has dark curls just like

my son, which makes me smile.

In a second, the sunshine through the bakery window

becomes too bright, as bright as fire.

Yesterday the boy ate with gusto

the hummus and olives his mother served,

was tender in the way of sons,

teased his mother, told her she was the best cook

in all the world, and she blushed.

He held her tight

when he hugged her close

for the last time.

This morning he shaved carefully,

washed with rose water,

repeated prayers, rhythmic as rain,

the soothing notes

bracing him for the light-filled path ahead.

In a second

we are on the floor

in pieces,

the bakery now a butcher’s shop.

How strange that

his blood, muscle, sinew,

last breath,

mix with mine,

in a puddle on the tiles,

which means

he is now

part Jew.

***

Empathy for the suicide bomber, horror at the death and destruction and irony are handled so effectively in these brief lines.

In her unflinching poem, “Canada is so polite,” Halifax spoken word poet and journalist El Jones describes “Canada as so bland, just miles upon miles of stolen Indigenous land.” Her poem is a lengthy, unflinching list of all the ways Canada does not live up to its image as courteous and kind. This poem was shared on the League of Canadian Poets Spoken Word Saturday, May 25th, 2024. I was unable to find a transcript, so please follow the link to watch and hear El perform “Canada is so polite.”

El Jones is a spoken word poet, an educator, journalist, and a community activist living in African Nova Scotia. She was the fifth Poet Laureate of Halifax. She is a co-founder of the Black Power Hour, a live radio show with incarcerated people on CKDU that creates space for people inside to share their creative work and discuss contemporary social and political issues, and along with this work, she supports women in Nova Institution in writing and sharing their voices. Her book of spoken word poetry, Live from the Afrikan Resistance! was published by Roseway Press in 2014.

Another spoken word poet who performs poetry of witness is Mohammed Moussa. He is a Palestinian freelance journalist, host of Gaza Guy Podcast, and founder of the Gaza Poets Society. His debut poetry collection, Flamingo, was recently published in English. He grew up in Gaza and attended Alazhar University before beginning his career as a reporter for various international news outlets. He is based in

***

In her poetry of witness about her mother’s life in residential school poet-journalist Rosanna Deerchild got to know her mother in new ways. That collection of poems became calling down the sky.

In Prairie Fire Magazine (2016) Deerchild shared some of those poems from calling down the sky:

“It is a poetically and narratively powerful collection in which Deerchild bears witness to her mother’s experience in residential school, the long-term impacts of that trauma, and both women’s resiliency. From the opening pages of the collection, she encounters the difficulties of telling a story long kept silent, of witnessing the story as it is told, and of living the consequences of that story. In addition to telling the residential school story, the work of the collection strengthens the connection between mother and daughter.

The first poem, “mama’s testimony: truth and reconciliation,”

opens with the following lines: “people ask me all the time/ about residential

schools/ as if it’s their business or something” (5). Deerchild makes an

important political and cultural statement by highlighting the implicit

violence we do in insisting that Indigenous people put their pain on display

for the sake of white settler education.

In calling down the sky, she encounters the trauma, and she simultaneously resists voyeurism, in part by drawing attention to the difficulty of speaking and of hearing.

In that first poem, Deerchild’s mother goes on to say why this request that she speak now, after so many years, is so presumptuous and so intrusive. From the speaker’s childhood, community denial has accumulated on official denial:

don’t make up stories

that’s what they told us kids

when we went back home

told them what was going on

in those schools (7)

Furthermore, empty apologies pile words onto an already

“unnameable” experience (9):

there is no word for what they did

in our language

to speak it is to become torn

from the choking (9)”

(https://www.prairiefire.ca/calling-down-the-sky/)

***

Writing poetry of witness does not mean poets who choose to write it presume to speak for others. Rosanna Deerchild collaborated with her mother on the story of her Residential School experience.

Sam Cheuk, Vancouver-based poet and Hong Kong Yan (Hong Konger), wrote brilliantly about the 2019 Hong Kong pro-democracy protests in his collection, Postscripts from a City Burning. I was glad to have Sam Cheuk as my sensitivity reader for the Hong Kong poems of witness in my new poetry collection, The Meaning of Leaving. Although he is not a journalist, Sam helped shape my poetry about Hong Kong both directly, and indirectly through example.

After teaching in Hong Kong for twenty years myself I can relate to Sam’s remorse about leaving his former students behind. “I used to be a teacher,” he tells us (55), “What am I to say / when a student responds, / after confessing I am / too chicken shit to stay / ‘We’ll fight for all of us’?”

In the next stanza of the poem Sam Cheuk shows us the bravery of young protesters facing possible reprisals in prison: “They announce their names, / yelling ‘I will not kill myself’ / while being dragged away.”

Cheuk’s guilt and grief come through strongly in the final stanza of that poem: “The student is still / messaging me via / an encrypted app, assuring / he’s safe for my sake.”

Here is my poem about witnessing student protests among other responses to the crackdown on freedoms by the Hong Kong government, especially in 2019:

Migration

I hope to

exchange my life for the wishes

of two million—we

can never forget our beliefs, must keep persisting….

--“Lo”, 21 year-old Hong Kong pro-democracy protester

The moths are most

active at night.

Their black-clad

bodies

swarm the streets,

like a miracle

hatching

defying

extinction.

A black moth

trembles

on a window ledge,

framed by a police

spotlight.

“Never give up!”

she shouts, falls backwards,

merging with dark

sky.

Well-wishers leave

pots

of night-blooming

jasmine

on pavement

where she fell.

One month ago,

another black moth

wings torn by the

teeth of the wind

probed a vein,

painted

her last

composition

on the wall in

blood. At 21

she must have felt

old,

her lungs singed

by tear gas and

pepper spray.

Careful to slip

past the webbing

of the stairwell

net,

she jumped.

A few students

come

for my nine

o’clock class.

Shuffling in their

black hoodies,

barely whispering

“Here”

when I call their

names.

I let the absent

ones

hand in their

essays late.

They might

graduate.

The state forbids

them

to choose their

leaders,

so they seem to be

leaderless.

On the streets of

Mong Kok

they remind each

other,

“Be like water,”

as Bruce Lee said.

Moths do not need

the sun,

their wings

vibrating

to heat their

muscles.

Many moths, their

lives

so short, do not

eat.

What do they live

on?

In my dream, the

Prometheus

silk moth eats

fire.

It burns from

within,

lands on fire

to burn the old

city down.

***

In her Quill and Quire interview Emily Pohl Weary refers to Carolyn Forché’s anthology, Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, which contains writing by poets who had experienced ‘conditions of social and historical extremity.’ She sees writing as a political act. Forché goes so far as to assert that the poem itself is a form of witnessing, and ‘might be our only evidence that an event has occurred: it exists for us as the sole trace of an occurrence.’

I agree that our witnessing through poetry is a record

of an event and of the feelings it inspires. Witnessing is often a political

act, whether through poetry or some other medium. For a large part of her career, Forché, who is now seventy-three,

has been described as a political poet. She says she prefers the term ‘poetry

of witness.’ Her poems ask again and again, What

can we do with what we see and live through? In a New Yorker magazine piece

about her, Forché’s writing is described as “a kind of dialectic, one in which

the truth of experience burns as brightly as the author’s intuition and

imagination.”

As you read this you might have been asking, why poetry of witness and not creative non-fiction or memoir? Traditional journalism has eschewed emotion. Margaret Atwood once said, “Poetry is condensed emotion.” There is a kind of answer.

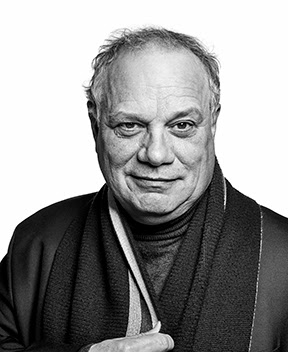

In 2023 Kate Rogers won first place in the subTerrain magazine Lush Triumphant Contest for her five-poem suite, “My Mother’s House.” Her poetry also recently appeared in Where Else? An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology. Kate’s poems have been published in such notable journals as World Literature Today; Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and The Windsor Review. She has work forthcoming in Writers Resist. Homeless City, a chapbook co-authored with Donna Langevin, launched in the first week of January 2024. The Meaning of Leaving is Kate’s most recent poetry collection. She is Director of Art Bar, Toronto’s oldest poetry reading series. More at: katerogers.ca/