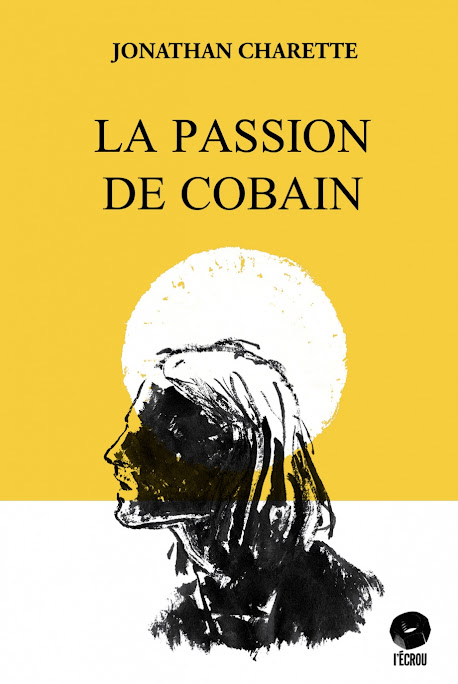

La passion de Cobain, Jonathan Charette

L’écrou, 2021

Now, I would never had thought of starting a book of poems centred on Kurt Cobain with a quotation by Leonard Cohen as an epigraph. And using it directly in English, after dedicating the book to his parents, certainly sets the tone for Jonathan Charette’s La passion de Cobain (Cobain’s Passion). There is an immediate access to experience from where we are (in this case, Montreal), regardless of languages spoken.

In part, I am sure, because of the repetition of the same images, but not wholly for that reason, I remember clearly learning about Cobain’s death, watching people on TV looking busy around his house, as I stared intently at the inside of the room where he lay, the mess of it all. I was a Nirvana fan, even though I didn’t get much of their music, let alone what was happening – I was too young for that. I did love the chaos, even though it embarrassed me. I had a hard time accepting that Cobain used drugs, I didn’t understand this whole suicide thing. I knew people did it, I just hadn’t been confronted with it yet. Nothing shifted in me on April 5, 1994, but the event certainly stuck with me.

Charette was young too. He wasn’t a fan, didn’t really know Nirvana when Cobain died. But he was aware of his death at the time, and seems to have become a fan in the following months. Really, he discovers how certain kinds of music can beautifully wreck you – something that Bon Jovi just could never do. I suppose I only had a few months on him, the advantage of age. We learn this, about Charette or a version of him who speaks (minus my own experiences) in the first few poems of this focused, ambitious collection. These poems chronicle a passage, a transformation, in plain, direct language, with sparse use of poetic devices – usually one or two strong metaphors or images per page. The first section marks time, skipping a few months in between each poem, giving a sense of what it was like to be a teenager in Québec in the mid-90s. The crowd Nirvana brought you to, if you were serious enough about music and about your generalized disgust.

The poems would work well even for readers without that shared intimate experience of space and time – but to get the full charge of each poem in the first section, its intimate associations, there’s no getting around being able to hear each song that’s mentioned. Most poems seem to be crafted around a reference to a Nirvana song, which lends its tone and its specific energy. Otherwise, in not immediately knowing the difference between “Endless, Nameless” and “All Apologies,” something would be lost (but it’s never too late to get into Nirvana):

cloud of haschich

cloistered in my

bedroom

after an oath of

racket

I improvise Endless, Nameless

forced to concede

some weight

nuage de haschich

cloîtré dans ma chambre

après un serment de vacarme

j’improvise Endless,

Nameless

obligation de jeter du lest (16)

Compare to this repetitive structure:

affection for a

girl

at night I prepare

an approach

while listening to

All Apologies

freezing up the

next day

unable to invite

her

to that Friday’s

dance

captive in the

role

of the moping

lover

I run my lines

while listening to

All Apologies

that song of demotivation

affection pour une fille

le soir je prépare une approche

en écoutant All

Apologies

blocage le lendemain

incapable de l’inviter

à la danse du vendredi

prisonnier du rôle

de l’amoureux qui se morfond

je répète mon discours

en écoutant All

Apologies

chanson de

démotivation (18)

The second section’s musical focus is on songs and artists we know Cobain to have loved, those we discovered because he mentioned them, or because they were associated with him. This section marks time in the same way as the first, but there’s a nice twist, which I won’t spoil here. These poems show to what point a life’s atmosphere is the same, no matter its outcome: “beyond disappointments / a placid constellation / where pariahs are sovereign” (au-delà des déceptions / une constellation placide / où les parias sont souverains, 36).

The same temporality as the first section, minus the references to specific months and years, reappears in the third section, which follows Cobain and Courtney Love’s daughter Frances Bean from birth to Cobain’s death. Rather than interrogating what it would have been like to live with Cobain, to be his daughter, Charette leaves the narration behind and explores what the symbols, the associations, the rituals, the social circles would be for a child who would simply take it for granted. I’ll pick a very obvious image for anyone who was into Nirvana when In Utero came out:

After the playful

dismembering

of the artificial

angel

Frances places the

organs back

into the tearful

hollows

[...]

a guinea pig’s

resignation

in spite of the

inversions

undertaker’s panic

horror disgust

sacrilege

the body is not a

dump

before the In Utero tour

Kurt replaces the pieces

of the mannequin

in love

with

Michelangelo’s Dying Slave

Après le dépeçage ludique

de l’ange artificiel

Frances remet les organes

dans les cavités larmoyantes

[...]

résignation du cobaye

malgré les inversions

panique du thanatologue

horreur dégoût sacrilège

le corps n’est pas un dépotoir

avant la tournée In

Utero

Kurt replace les pièces

du mannequin en amour

avec L’Esclave

mourant de Michelangelo (52)

The next section presents a similar attempt to imagine and describe a symbolic and affective disposition – that of Cobain’s last days. Our awareness of the coming tsunami shifts to its building, and Charette lets its advance slow down considerably as it gains height. The central element to which Charette returns, the trigger to Cobain’s fall, is the “treason / absolute treason / of being made into a monument / while living” (traîtrise / traîtrise absolue / d’être changé en monument / de son vivant, 69).

Where a true shift in voice takes place – perhaps where Charette feels or attempts no identification with his character – is in the second last section, where Courtney Love speaks both as a widow and in her now famous and unfortunate role as the accused in what remains a suicide.

“A blonde boy screams inside my lungs. The parasite enmeshes my system. Despite the discomfort, repulsion to dislodge it. Certainty of the damned: I am carrying my husband. Folly! Delirium! Solace.”

Un garçon blond hurle dans mes poumons. Le parasite phagocyte mon système. Malgré le malaise, répulsion à le déloger. Certitude d’une damnée : je porte mon mari. Sottise ! Délire ! Réconfort. (86)

Charette gives voice to Love who was robbed twice of herself. In five prose poems with short stanzas, she protests as much as she sings incantations and casts spells. But this voice is not meant to be Love’s own voice, there is no search for her mannerisms, her speech, her idiosyncrasies – anymore than anywhere else in the collection. This section offers the poems that are most detached from reality, the most sublimated and abstracted from real-world content, the rawest and most violent, with the strongest images – the closest to the affective life of rage and loss.

I’ll keep the coda secret. Its mystery, its imagery, and its optimism, its distance as well, all contribute to highlight the effects of the passage of time on all the pain, the hurt, the loss and the being lost that the poems carry forward and splay out so well. Besides, I’m not done with the book yet.

Jérôme Melançon writes and teaches and writes and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His most recent poetry collection is En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He is also the author of a bilingual chapbook with above/ground press, Coup (2020), and of two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016), as well as one book of philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018) and a bunch of different attempts at figuring out human coexistence in journals and books nobody reads. He’s on Twitter and Instagram at @lethejerome and sometimes there’s poetry happening on the latter.