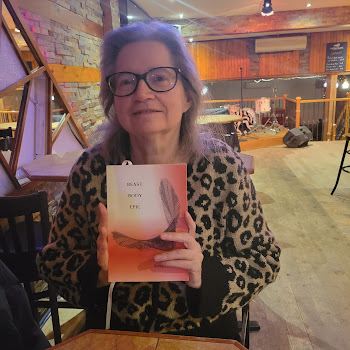

AJ Dolman’s

(they/she) debut poetry book is Crazy / Mad (Gordon Hill Press, spring

2024). A professional editor, Dolman is also the author of Lost Enough: A

collection of short stories, and three poetry chapbooks, and co-edited Motherhood

in Precarious Times (Demeter Press, 2018). Their poetry, fiction and essays

have appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, recently including Canthius,

Arc Poetry Magazine, QT Literary Magazine, and The Quarantine

Review. They are a bi/pan+ rights advocate living on unceded Anishinabe

Algonquin territory.

AJ Dolman reads in Ottawa on Sunday, March 24, 2024 as part of VERSeFest 2024.

Amanda

Earl:

Crazy/Mad is full of puns, and language play: alliteration, assonance,

nouns turned into verbs, unique collectives such as “a sorrow of stones.” You

have a poem for John Lavery, who was an ingenious word worker. Can you talk

about your love of sound and word play? Was your first language Dutch? How does

the knowledge of other languages affect your English play with words and sound?

Would you like to say more about Lavery?

AJ

Dolman:

John Lavery was indeed a genius at language and I miss him, and the thrill of

reading new writing by him, terribly. We didn’t always agree, but we respected

each other, and he never let me off the hook, always prompting me with “So,

what are you working on now?” He was able to blend French and English

colloquial language into a joyous whirlwind of syllables that sounded perfectly

right in its wrongness, boldly direct in its meaningful meaninglessness. He was

one of those writers who could simultaneously do the thing (such as writing

what was ostensibly cop fiction) while utterly subverting the thing, playing

both ends to the middle, as it were. I learned a lot from him, but mostly that

we are all allowed to play with these toys of trope, language, genre, sound, meaning.

And

yes, my first language was Dutch, my parents and two sisters having immigrated

to Canada 14 years before I was born. I was a shy kid, and starting school in a

language I barely spoke didn't help that. But the Swiss immigrant kid in our

class (Fabienne, still one of my best friends) and I became friends, and she

and I muddled along in a sort of made-up Swiss-German/Dutch/English hybrid of

language and gestures until we could fully make sense of ourselves and others

fully in English.

My

Mam was my way into a passion for language, for how intensely its rhythms could

be played. There’s always been a sense in my family that my mother could have

been a great writer if her circumstances in life had been different. She told

the best (also worst) bedtime stories, because she would fully embody the

characters, so every witch or wolf scared the life out of me. She was also an

alcoholic, as was my Dad. Years later (she got sober when I was a teen, and

stayed that way the rest of her life), my mother easily admitted she’d been

terrible at parenting. But she certainly was a great language and drama teacher

to me.

AE: You dedicate the

book, not to one specific person but “to the worried, the lost, the uncertain

and the afraid.” Throughout the book, you address issues of social justice

through the lens of mental health issues. Those who deal with mental health

issues are more often than not erased, harmed by a system that wishes they

didn't exist and marginalized. You write about the issues of labour, poverty,

sexual orientation, gender, racism and colonialization. At some point in my inculcation

into the writing of literary work, I got the idea that one wasn't supposed to

write overtly about such issues. Did you

also have that impression and how did you override it in order to write and

share poems, such as "Delusions of grandeur?"

AJD: The Canadian

poetry (and fiction, for that matter) that I first encountered, and that was

esteemed by those guarding the CanLit towers when I arrived at its gardens

definitely had a silencing effect. It was those quiet examples of “this is what

we write about here,” which an emerging writer can easily interpret as “nothing

else will be accepted.”

There

were exceptions, of course (one of my favourite older books of Canadian poetry

is 1978's The Ghosts Call You Poor by Andrew Suknaski, a mad prairie

poet I didn't discover until my 30s). But most examples I saw came from the

States—Ginsberg, Clifton, poets who were queer and/or Black and/or stemming

from poverty, and who were angry out loud.

I

was taught to be quiet. Children were to be seen and not heard, and me having

first an accent, then secrets of gender and orientation, I doubled down on

being quiet. When I was ready to not be as quiet anymore, as an adult, a

student, a writer, I was told “We don’t publish political poetry” and “Your

message is too overt; stick to metaphor.” Don’t get me wrong, I love a juicy

metaphor. But if not right now, in every way we can, then when and how is the

best way to declare what we have seen, and to demand better for ourselves and

others?

I

didn’t trust my own voice for a long time, and repeatedly being told by editors

turning down my work that my writing conveyed “a strong voice” felt like being

punched in the gut with a silk glove, a surface nicety that did nothing to mask

the jab. Yet, audiences and readers seemed to appreciate what I was doing. And

I saw more and more people, often from far harsher backgrounds and with more intersecting

identities than me, being brave. So, what right, then, do I have to not try to

be louder, to be braver, if I can? For myself, but also for others.

AE: While there are

glimpses of joy in parental-child relationships, such as in “Inversion,” where

you show a child’s humour and intelligence, your poems are unflinchingly candid

on the physical and emotional trauma of giving birth and of being a mother,

such as in “Perinatal panic disorder” where you write “children a choice you

can’t undo,/like suicide.” Or in “Female rage,” where you write about

Clytemnestra: “death in masses/of children,/stopping up/a rampant womb that’s yielded/crops

of babies.”

You

include a poem about Andrea Yates, who drowned her five children. What made you

want to openly depict the struggles of motherhood?

AJD: No one in my

poems rages against their children themselves. What they rage against is lack

of agency. And, I don't, in any way, mean to speak for any other parents or

their experiences.

I

adore my kid. He’s a teen now, and I have loved being part of his life and his learning

and growth. But, everything about pregnancy, birth, and especially the first

several years of his life, was immensely traumatic for me. Part of that, in

retrospect, had to do with gender dysphoria, though I didn’t realize what it

was at the time. Part of it was going into the decision to have a child while

mentally ill, which for me came with decisions about medication, with guilt in

advance about the poor parent I thought I might be, with concerns around

heredity, etc.

As

for Yates, I watched documentaries and read numerous articles about Andrea

Yates after the she was found to have killed her children, all of whom were

still little, one only six months. Yates was ultimately diagnosed afterwards

with severe postpartum depression, schizophrenia and postpartum psychosis. What

happened was horrific. Yet, what, in the aftermath, makes it still harder to

wrap our minds around is the questions around her intent, let alone her capacity

for rational thought. People in her life swear Yates never hated her kids. It

seems she loved them deeply, and what happened was a horrific confluence of

severe mental illness, her having been victimized her entire life, and her

religious beliefs leading her to decide she could protect her children from

some greater harm awaiting them in their futures by killing them and, thereby,

sending them safely to her god to lovingly care for instead.

I

used to think my fascination with the story was from seeing it as a worst case

scenario for mental illness and parenting. But I realized at some point that

what I was most consumed with was that, even in extreme madness, she behaved

like so many other people, by responding to her own lack of agency by taking

away agency from others. It's not what she consciously decided (she was found

insane on retrial, and thus not criminally responsible for her actions), but it

was the end result of what she did. And we see that same behaviour, in people

technically sane (technically, because, for example, I cannot imagine anyone

"sane" believing they can and should own another human being), time

and again throughout history.

AE: You deal with

mental health issues in this book in a way I rarely read in contemporary

poetry. Can you talk about how the collection came together and how you decided

to center it around this theme?

AJD: I write what I am

passionate about, and this is a thread that has run through my life, through

generations of my family, among friends and colleagues. And now, especially

since the start of the COVID pandemic and general acknowledgement of the

climate crisis, anxiety and depression, in particular, seem to be running

rampant. Of course they are. Look at what is happening. I am honestly amazed we

aren't all just breaking down in the streets daily. Yet, Madness was one of my

most fundamental fears for as long as I can remember. Not the being Mad itself,

but to be considered crazy, to be sent away, institutionalized, diagnosed.

Voicelessness, again.

So,

that thread ran through many of my poems, too. And I’ve talked before about the

impact Jon Crispin’s photographs of the confiscated luggage of patients of the

Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane in Upstate New York had on my view of

madness as a viable subject. Being invited by guest editor (and absolutely

brilliant poet) Roxanna Bennett to contribute fiction to a Matrix issue

on Madness also helped me feel this was a topic I could make work for an entire

book. As for the actual structuring, some great fellow poets and editors,

including Deanna Young and Stuart Ross, looked at previous versions of the

collection, and provided great guidance that helped me make both the poems and

the book's structure more cohesive. But, it wasn’t until Shane Nielson at

Gordon Hill Press pushed me to make the book more what it already almost was by

then that I fully embraced it. I am delighted by the end result in a way I ‘think

I could have anticipated.

AE: Your portraits of

the prairies and the suburbs is full of Gothic landscapes and scenes of

horror. Can you talk about influences?

Where does your sense of the Gothic and of horror come from?

AJD: Between the ages

of two and 15, I grew up on a hog farm in Alice Munro country, Wingham, a

foundry town in Huron county, southwestern Ontario. In the early 80s, the

bottom dropped out of the hog market and desperation ran through the

communities like a rush of Crown Royal. It suddenly cost more to raise a hog

than you would ever make on it per pound. But who would buy your farm? Eventually,

the banks refused to even foreclose on any more properties. They were holding

too many absolutely unsellable farms already. So you couldn’t even claim

bankruptcy. You could just go deeper and deeper into debt, with no hope for you

or your family or the dreams you brought with you. Or you could go to jail for

insurance fraud after burning your buildings down. Or you could hang yourself

from the rafters and make it all someone else’s problem.

Our

own, brick farmhouse, its yellow paint repeatedly peeling in the summer

humidity, was from the 1800s. Hanging in our bykeuken (uninsulated, room that acts as both a

mudroom, often a laundry room, and the informal kitchen where the working wood

stove is, where meats are hung and dried, and where the farmhands eat their

lunch) was a damp-eaten, ornately wood-framed, black and white photo, maybe

even a lithograph, come to think of it, of the stern looking couple who had

founded our farm. They would stare down at the farmhands or family as we ate

lunch.

My

first real job was picking rocks in the neighbour's fields so their dairy cows

wouldn't break their legs. In our own fields, my dad had me stoppering up

groundhog holes with more rocks, as part of his plan to protect the cattle we

grazed temporarily pre-slaughter from the same. My dad would then run water

into the remaining open holes to try to drown all the groundhogs and their

babies. I doubt it worked, since I doubt I found every exit. But you get the

vibe here. Two alcoholic immigrant parents in a rural gothic dystopia.

Then,

later, I married a horror writer.

AE: Your poems often

end with endings cut off, which feels like a disruption of status quo poems

where there's an epiphany or full circle ending. Can you talk more about ending poems with

conjunctions and other unusual endings? Any pushback from editor?

AJD: The majority of

pushback I’ve received from editors over the years has been when I try to wrap

my poems up with an inauthentic, pretty bow, to round them out and make them

neat and tidy and "finished". But that is not the nature of my

content, or my writing style, or my mind. How can I end an exploration of the

mess (glorious at times, but absolutely a mess) that we humans are, by coming

to a single, poignant, epiphanic conclusion? And, what thought is truly

complete? What is the end of a journey? At best, we are forever in some sort of

motion, learning along the way, changing always. I have made my peace, and so

seemingly have my favourite editors, with the fact that I am not, nor will I

ever be “a sensitive man.” I don’t have it in me to “write poems about flowers.”

But I’ll stay at the bar with you for the telling of stories that blend into

both each other and the night, until

;)

AE:

Joy is fleeting in the book, and when it appears, it is often associated with

the speaker's memories of queer experiences, such as “Obsessive traits.” There

is also joy in the play of language and the metaphors you use, the incantatory

lists. What, if anything, brought you joy when you were writing these poems?

How do you reconcile joy with the bleakness inherent in the collection? I loved

the bleak imagery here. I felt it painted a reality that I understand, that you

have not glossed over the direness of the 21st century. Do you think this is a pessimistic

book? Where do you see hope if you do?

AJD: I see a lot of

joy in these poems, but it is often the joy of expressing myself, and of

standing up, for myself and others. Tears are important. Tears can help you

process, can get you ready. But, to stand up and speak is to be filled with the

joy that you can, that you are, that you know you have to. That you have been

given the opportunity, and you are ready to give it to others. I am not joyful

that we continue to shut people down. But I feel the enormous joy of gratitude

that I can say “Look. We are continuing to shut people down. And it is time to

listen to them instead.”

AE: The poems in

response to Jon Crispin’s photographs of the abandoned suitcases at Willard

Asylum for the Chronic Insane fit really well in this collection. Can you talk

about how you found out about Crispin’s series and why it resonated with you?

AJD: Jon is one of the

few artists whose work moved me to reach out directly to them. I forget how I

came across his online gallery, but I recall he had a fair number of suitcases

and other baggage shot already, though he has done hundreds more since, I

believe.

The

Willard Asylum, which is a real place in upstate New York, eventually became a

hospital before ultimately shutting down in the latter half of the 1900s. It’s

a terrifying place, visually, geographically, and conceptually. The luggage Jon

shoots was all found in a long-closed-off wing in the attic while developers

were considering options for the property. From a shoe shiner’s work kit, to

prosthetic limbs, embroidery tools, photos and love letters, pretty shoes and

ribbons, the bags contained all the objects that were taken from new residents

and never returned. Many of the patients, or inmates, lived out their lives,

short or long, at Willard and were buried in its cemetery.

These

were the days, from the turn of the to mid-20th century, when you dealt with

someone who was problematic (your queer cousin, the wife you wanted to leave

for another woman but couldn’t divorce for religious or other reasons, the son

who came back from the war “changed,” your husband who wouldn’t get out of bed

anymore, your sister who heard voices, your white neighbour who wanted to marry

a Black woman, your girlfriend who tried to kill herself, and anyone else who

was too much or too bothersome for you to handle) by sending them “away.” And

Willard was far away, indeed.

For

me, the place, and Jon’s striking photos of the last, lingering intimate

details and priorities of these people, many of whom were intended to be

forgotten, resonated deeply with me. Here was my worst case scenario, and also

the very case against it, made manifest. To be diminished, discounted,

discredited, deemed valueless and made into nothing but an absence, someone

else’s regret. What Jon shows is in his photos is proof of life, however. Proof

of value and individuality, of creativity and connection and everything that

makes us human. That makes us worthwhile for the sheer fact that each of us

exists. No matter our state or how we present to the world.

AE: Can we start a

playlist for Crazy/Mad? I'd like to open with Lorde’s “Writer in the

Dark.” What would you include?

AJD: Absolutely! I

love books that come with playlists. I first saw it in queer romance (I chaired

a Bi Book Awards Romance jury for a number of years), and am thrilled to see

the idea spreading. Art always influences art. And music has been very

important to me my whole life. I’ve put this one together. Honestly, I find

Lorde a bit dodgy, politically/ethically, though I have included “Writer in the

Dark” here, because it is, regardless, a good song: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/0k8jRw6K9DapwhnJnbwQZO?si=48de2af31c3b4489

Most

are what you might expect, but “Het Kleine Café” (the little cafe) is a song my

dad would listen to over and over again when I was growing up. It’s mournful,

on the one hand, but is also a beautiful lovesong to a little, broken down pub,

and the sense of community you get from going somewhere where you feel everyone

is equal and content. Het Kleine Cafe is not fancy (“the only food you can get

there is a hard-boiled egg”), but, as the song says, “It is a very good Cafe.”

Amanda Earl (she/her) is a

queer writer, visual poet, editor, and publisher who lives on Algonquin

Anishinaabeg traditional territory, colonially known as Ottawa, Ontario. Earl

is managing editor of Bywords.ca, and editor of Judith: Women Making Visual

Poetry (Timglaset Editions, Sweden, 2021). Her books include Beast Body

Epic (AngelHousePress, 2023), Genesis, (Timglaset Editions, 2023), Trouble

(Hem Press, 2022), and Kiki (Chaudiere Books, 2014; Invisible

Publishing, 2019); A World of Yes (Devil House, 2014) and Coming

Together Presents Amanda Earl (Coming Together, 2014).

Her

latest chapbook is The Seasons, an excerpt from Welcome to Upper

Zygonia (Full House Literary, 2024). More information is available at

AmandaEarl.com and https://linktr.ee/amandaearl.

You can also subscribe to her newsletter, Amanda Thru the Looking Glass

for sporadic updates on publishing activities, chronic health issues and joy in

difficult times.