When I began research on Judith: Women Making

Visual Poetry, I had only a vague notion of the women visual poets and

artists who had gone before, but I had heard a lot about the men. I knew of Ian

Hamilton Finlay and Bob Cobbing from the UK, bpNichol from Canada, and the Noigandres

Group in Brazil. Emmett Williams’ An Anthology of Concrete Poetry,

published by Something Else Press in 1967, is considered to be a foundational

anthology, is freely available as a pdf on UbuWeb, and has been reprinted in

the 21st century in different versions, including one in Braille, but

it includes only two women. In fact, other key anthologies from that era range

from between 0 and 6% women. Anthologies publishing the work of visual poets in

the 21st century have a representation of between 12 and 21%. We’ve

come a long way, baby. Yeah right.

I’ve seen Cobbing, Finlay, Nichol and the Noigandres

Group written about and mentioned all the time, but I hadn’t seen or heard much

about women concrete poets of that era.

I started making visual poetry in the mid aughts and was

told by numerous male visual poets, editors, and publishers that few women made

visual poetry. I didn’t know of the rich and empowering history of women practitioners,

whether they were called concrete or visual poets or artists. There have been

many. It would have galvanized my practice at the time. This is one of the

reasons I believe Judith is a necessary book.

I see connections between the work of earlier women

makers of visual poetry and contemporary practitioners. It is my hope that

women today and tomorrow will be inspired to create and explore the rich

history of women making visual poetry. That this visibility will lead to

creating and opening spaces for women, knowing that they are not alone and that

the work they are doing is valid.

The publication of Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959-1979 by Primary Information in 2020 features fifty women creators and is a

welcome and long overdue book. Many of these women began working with concrete

poetry in the sixties or earlier but few were included in the anthologies of

that era.

So overshadowed are historical women visual poets and

artists working with language elements that many people don’t have any idea of

their achievements and work. Doris Cross is considered to have been the originator or an early practitioner of

erasure poetry. Beginning with the dictionary in 1965, she used techniques such

as overpainting and collage to erase sections of text. Today, there are

numerous women and non-binary artists continuing this tradition. Erase the Patriarchy, An Anthology

of Erasure Poems edited by Isobel O’Hare was

published by University of Hell Press in 2020. Yasmine Seale, a writer and translator from

Arabic and French is currently working on a new translation of The Thousand and

One Nights, using erasure. Sarah J. Sloat’s great book, Hotel Almighty

published by Sarabande Books erases Stephen King’s Misery. The Spanish

artist, Mar Arza cuts text out of book pages to

create stunning hanging sculptures.

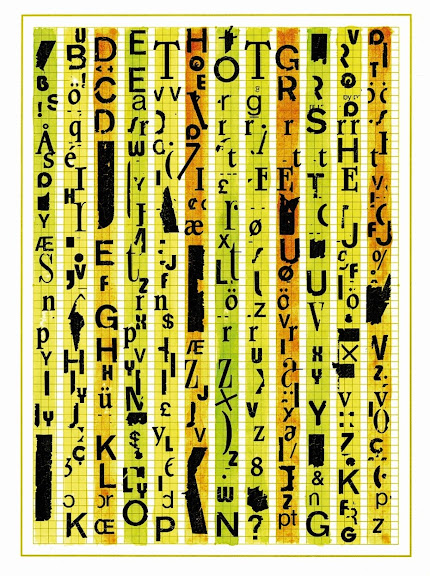

Judith’s contributor,

Ines Seidel of Germany has used similar techniques in her work, cutting out

sections of newspapers, so that collective stories take on the shape of the

news and making them tactile and wearable, showing a relationship between the

body and the news. From our list of over 1100 women making visual poetry,

published in Judith, we have identified at least forty-four women using

erasure techniques, and I’m sure there are much more.

Flora F.F. Stacey is credited or rather rarely credited

as the first creator of typewriter art in 1898 with her typewritten illustration of a

butterfly. I never heard of her until I read Typewriter Art

published in 2014 by Lawrence King Publishing and edited by Barrie Tullett. It turns out that there were many women who

worked with the typewriter, Letraset, rubber stamps, letterpress, carbon paper,

the mimeograph machines, photocopying and other early technologies.

In her essay, Handle with Care: A study in (poetic) fragility, first published in Jacket 2, and republished in Judith, Kate

Siklosi refers to “Jewish wartime refugee Mira Schendel’s “carefully layered panes of rice paper covered in dry transfer

collage, where the letters appear pristinely englassed, trapped in amber, are

exemplary of the limitations and liberations of the medium.” Annalisa Alloatti,

one of the women featured in WiCP, used a Braille machine to create “thick

columns of dots that troubled the concepts of verbal and pictorial meaning.”

Contributors to Judith, such as Johanna

Drucker, Kate Siklosi, Petra Schulze-Wollgast and Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, who also

appears in Women in Concrete Poetry, have made use of obsolete or older technologies

in their work as has Dani Spinosa with OO: typewriter poems; however,

even in contemporary articles about such, not one woman is mentioned.

In her foreword to Judith, Drucker talks about

working in a male-dominated print shop in the seventies in California, an

environment that wasn’t particularly welcoming of women.

In the biographies in WiCP, you can read about the

roles of the women in various artistic movements and groups, as participants or

founders, such as Lettrism, the Noigandres Group, Spatialism and more. One of

these is Sonja Åkesson, a Swedish poet who the book refers to as “a leading

figure in the New Simplicity Movement.” Pris, her collage book used readymades

and cut outs from advertising catalogues to represent the everyday. In Judith,

Ankie Van Dijk, Hiromi Suzuki, Cinzia Farina, Erica Baum and Mado Reznik continue

the tradition of using collage techniques in their work, salvaging materials, combining

photography and vintage magazines, engaging with play, materiality, and minimalism.

Bianca Menna, used the pseudonym Tomaso Binga to

parody male privilege and made concrete poems written in an invented language

that resisted patriarchal norms. Her Alphabeta murale turned positions of the body of a woman into an invented alphabet.

Looking at her work now, I think of how I would have longed to know about it.

Ana Hatherly played with the illegibility of writing through her

drawings . Invented languages, alphabets, and dream symbols

are the stuff of asemic writing, a form with numerous women practitioners

today. In her essay in Judith, “A World of Signs: Women of Asemic

Writing,” Natalie Ferris writes that asemic writing gives women the chance to

challenge the “patriarchy’s monopoly on meaning.” In Judith, asemic

writing is a major thread in several contributors’ work. Dona Mayoora and Rosaire Appel explore connections between

light and line. Ferris also discusses

the reclaiming of a traditionally male-dominated art, Arabic calligraphy and word painting by

women, such as Firyal Al-Adhamy, whose work appears in her essay.

Maybe we can trace the use of computers for visual

poetry to artists such as Gay Beste, who worked at the University of

Minnesota’s computer lab and photocopied hand-drawn letters and plotted them on a ColComp plotter. Her work evokes my own visual poetry made using Adobe Photoshop and

Illustrator, or the work of contributors to Judith: Kimberly Campanello, Iris Colomb, and Judith Copithorne.

In her essay in Judith, “Light and Code: Digital

Ecologies of Poetic Form,” Fiona Becket presents the virtual reality work of

Australian artist Mez Breeze and the extended poetry of Stephanie Strickland, discussing how

such work responds to and augments the human sensorium and expands the work of

electronic literature. Other future trends in visual poetry might include work

with environmentally friendly materials such as bio-resin. For example, Astra Papachristodoulou’s poem objects

made with bio-resin are featured in Judith.

In my statement in Judith, I name Copithorne as

an influence on my own work. She began in the sixties by making hand-drawn work

and has used a range of techniques and media. In her most recent work, she

works with Adobe Illustrator to create colourful combinations of words and

geometries. Judith includes colourful, vibrant work by Mara P. Hernandez and Satu Kaikkonen.

American artist, Amelia Etlinger appears in WiCP. She

was not well known in North America in her lifetime. She made everything from

four-foot high tapestries to two inch bundles of poem-like packets that

combined fabric, beads, Japanese paper and found materials. She has only two

pieces in WiCP and they don’t represent the range of her work, which can better

be studied on the University at Buffalo’s digital collection, the Amelia Etlinger Collection. Judith explores the thread between craft and language in a

round table interview with women who use needlework, textiles, and elements of

language in their art. Part of the interview is published in the book and the

entire interview will be published on Timglaset Editions.com.

Mirella Bentivoglio was an Italian artist, performer, concrete poet and writer who, if I’m

understanding what I’ve learned, became a curator when she discovered the poor

representation of women in the Italian art community. She went on to curate

twenty-seven international exhibits of women artists and concrete poets and

established a network of women. Poesia Visiva: la donazione di Mirella

Bentivoglio al Mart was published in 2011 by Silvana and contains over 300

works by women visual poets and artists. It’s a revelation! Bentivolgio is the

model and inspiration for my curatorial work with Judith and other

initiatives to learn about and amplify the voices of women, 2SLGBTQ, BIPOC and

D/deaf and disabled writers and artists. It’s an ongoing labour of love.

Please go to our IndieGoGo Crowd Funding Campaign to support the publication of Judith:

Women Making Visual Poetry: A 21st Century Anthology,

forthcoming from Timglaset Editions, May 2021.

Amanda Earl (she/her) is a

queer, polyamorous, pansexual feminist who writes and publishes from her 19th

floor apartment in downtown Ottawa, Canada. Earl is managing editor of

Bywords.ca and fallen angel of AngelHousePress, and the editor of Judith,

Woman Making Visual Poetry, forthcoming from Timglaset Editions in 2021.

Her poetry book, Kiki (Chaudiere Books, 2014) is now available with

Invisible Publishing. She’s the author of over 30 chapbooks. Her most recent

chapbook is a field guide to fanciful bugs, a visual poetry book of

whimsy published by above/ground press. Visit https://linktr.ee/amandaearl for

more info or connect with Amanda on Twitter @KikiFolle.

Accompanying image: Ines Seidel – Wearing the News II,

2020. Also published in Judith, Women Making Visual Poetry, A 21st Century

Anthology, Timglaset Editions, 2021.