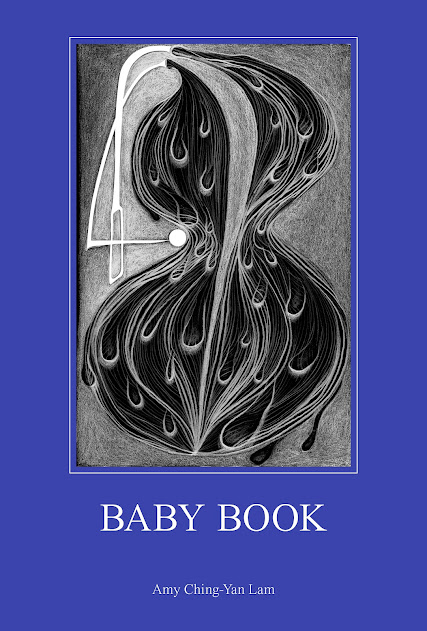

Baby Book, Amy Ching-Yan Lam

Brick Books, 2023

The latest from Tkaronto/Toronto-based artist and writer Amy Ching-Yan Lam, author of the speculative fiction Looty Goes to Heaven (Birmingham UK: Eastside Projects, 2022) is the full-length poetry debut Baby Book (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2023). Ching-Yan Lam utilizes a compelling meditative structure to her stretched out narratives, where the point of each poem is suggested to be in one direction, if any, instead sneaking up from another. Offering poems that open large questions around story and storytelling, she speaks of stories told, poured and passed down in their tellings and retellings. Is a story retold and remade a matter of regeneration or one of loss? She writes of family, including elements of continuity, displacement and origins, and how language can be mangled, misunderstood and manipulated. Her stories appear to meander, until one realizes that every step, every sentence and phrase, was highly deliberate, and provided the only logical journey towards a remarkably clear, precise and complex portrait. “In the beginning, the ground was the milk of beans,” she writes, to open the poem “LAND MADE OF FOOD,” “until it was boiled and squeezed into tofu. // Then hot sauce shot up from below and filled up the seas. // Rocks appeared—peanuts. // Then trees / with leaves and roasted nori / and trucks of nougat. // When it rains, it rains perogies.”

She writes of belief, and how such beliefs, such as with any other story, can be turned, confused and reworked, whether deliberately or across time, as well as how such stories can shift beyond the borders between cultures. “This week I am learning about the truth of expression.” she writes, as part of the sequence “ENGLISH ACCENT,” “My teacher says that if you smile, even when you are feeling sad, / you can still receive some of the benefits of being happy. / Even if you are simply smiling while sad. / He says that shame is similarly a physiological reaction. / It exists in your body and you can get rid of it with a physical / action.”

I hesitate to call these pieces prose poems, although they are poems structured in a form of narrative prose; her extended sequences exist from the bones and flesh of the narrative sentence, many of which collude to form prose blocks, but not always, and not necessarily. It is through the order she places her sentences that provide her narratives their power. As the six-page extended piece “ENGLISH ACCENT,” a poem that moves through navigating a series of narratives foreign to one’s own, ends:

Decades of no apologies or fake ones.

Decades of art about war.

Art that is fluent, rhetorically successful.

A beautiful carved wooden box.

That which blocks the truth is physical.

It’s a hot, stuck feeling in the body.

It’s a heavy heat. It’s a heavy box.

The physical remains physical.

The physical can be moved.

The physical can be destroyed.

When destroyed, it doesn’t disappear.

But it can be moved.

There is something curious as to how this book-length exploration on the connections and disconnections of family and family stories echo further other titles that Brick has produced since the publisher/editorial shift a few years back, a particular thread of titles that would include Andrea Actis’ Grey All Over (2021), David Bradford’s Griffin Prize-shortlisted Dream of No One but Myself (2021) and Nanci Lee’s Hsin (2022). Each of these, in their own way, as well, offer book-length explorations through new and unusual structures, allowing the shapes of the poems to provide startlingly fresh perspectives on the otherwise-familiar complications of family, cultural collisions and the disappearance of stories. Offering a tale of her grandmother and the slow release of family stories through “WE PRAY BEFORE DINNER,” Ching-Yan Lam writes:

I know why you’re

asking me so many questions.

Why?! I said.

She said, Because

you want to make a movie of my life!

Oh, I said.

Other facts have

been told to me in the same way.

The other day in

Chinatown:

A woman with white

hair, in soft flowered pants, let out a big

loud sigh.

She leaned herself

against a fire hydrant.

She lowered her

plastic shopping bags to the ground.

She said, Aiya, so

painful!

I went over and

asked if she needed help.

She said, No, it’s

OK, I’d rather walk.

She said, Do you

know what the doctor told me?

The doctor said the only option is to chop the leg right off. Yes,

that’s what the

Western doctor said. And my daughter told me,

If you chop it off

I’m not going to push your wheelchair for you.

I said, Oh my god.

Your daughter said

that?! I asked.

She said, Yes.

this is the way human life is.

Then our conversation

ended.

Born in Ottawa, Canada’s glorious capital city, rob mclennan currently lives in Ottawa, where he is home full-time with the two wee girls he shares with Christine McNair. The author of more than thirty trade books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, he won the John Newlove Poetry Award in 2010, the Council for the Arts in Ottawa Mid-Career Award in 2014, and was longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize in 2012 and 2017. In March, 2016, he was inducted into the VERSe Ottawa Hall of Honour. His most recent titles include the poetry collections the book of smaller (University of Calgary Press, 2022) and World’s End, (ARP Books, 2023), and a suite of pandemic essays, essays in the face of uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022). He spent the 2007-8 academic year in Edmonton as writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta, and regularly posts reviews, essays, interviews and other notices at robmclennan.blogspot.com