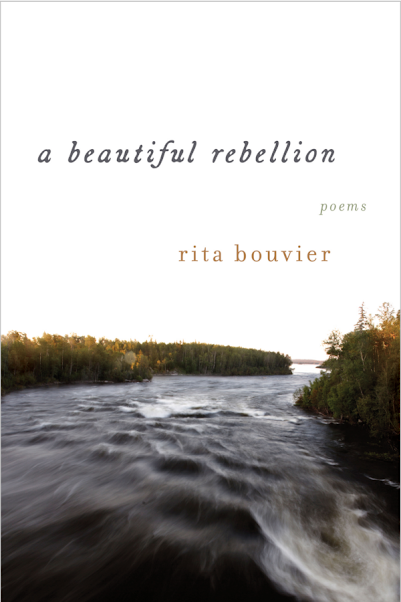

A Beautiful Rebellion, Rita Bouvier

Thistledown Press, 2023

Rita Bouvier likes being surprised. The beautiful rebellion she mentions in her title is that of reality against expectations and attempts at controlling it. It is found in children, in wasps, in history, in bodies – all surprising, and all skirting expectations.

The round dance, specifically, with the joy, beauty, and togetherness it creates, and its ability to literally feed people by drawing on traditional practices, stands as the illustration of rebellion. Bouvier presents her understanding of rebellion as deeply Métis. It does not focus on the armed resistance of the past: Louis Riel becomes important not for his political or military actions, but instead for refusing to be typecast as insane and have his actions erased. Bouvier also finds rebellion in the Anishinaabe performance artist Rebecca Belmore’s artwork; “blood on the snow” is mentioned, and “Facing the Monumental” inspires and is present in two poems (and “blook on the snow” was important enough that she brought a photograph of the installation to a poetry workshop I attended for others to draw upon).

This rebellion opposes the harm done to children and the wider massacres, erasures, injuries, and thefts committed against Indigenous peoples are non-human peoples, but also those she witnesses around the world. She expresses “a desire to know what makes us human / as if knowing might save me” (86). She also shares the opposite, in an act of seeking balance: “it is up to you it is up to you / to take back your humanity and selfhood” (52). These breaths within lines recall the speech of someone who knows thoughts are coming and knows to take the time to let them arrive. Humanity is an opening to what it is not: in “facing the monumental,” the monumental is everything that comes before humanity in the order of things; its monumentality is the extra-ordinary, the immense – the ability to turn to what is not ourselves, to create respectful relationships, to better human life, to nurture.

Bouvier does not only witness rebellion, she also engages in it. Her poems are full of words and sentences in Mitchif and nêhiyawewin. She ensures the languages are noticed, seen, heard, and known to be alive and well. She wants her readers to know she is Métis, to find strength in the strength she can share. Her presence in the poems is vital to their movement. The speaker is the poet; the poet never forgets that she is speaking. The words seem full of simplicity, but in fact are only direct, shaping the reading so that interpretation is not the matter. Interpretation is too risky where peoples have difficulty speaking to one another and treating one another as human; instead Bouvier entrusts us with a key and shows us the way in.

Perhaps I tend to see political philosophy in more places than is warranted – yet even by that standard, Bouvier’s are strong political and philosophical poems. She creates “an awkward moment” by recounting the harms of colonization and adding marginal comments to add. She names, and she does not enter the metaphorical register so that after all the colonial stratagems and structures are named, there remains the full force of language:

as if you

could exempt yourself

from the ethos of

the land

its aliveness its wildness (it will haunt you)

But she does use allegory, as in “one late autumn day” (45), where a story about herself, as a child, stealing hazelnuts from a squirrel and being punished for it, opens the way for those with good intentions to reflect on the difficulties of reconciliation. This poem shows the allure and wonder of what is encountered for the first time, the urge to take it, and the harm it brings:

stored deep in the cool dark earth

I discovered

the hazelnut had

lost its sting

with no regard for

my sister squirrel

I stripped her

nest and took it all

Bouvier often summons memories, and welcomes the additional memories she encounters as she moves through them (see for instance “a winter’s day in Île Bouleaux”). This movement of welcoming extends to the joy she sees while watching others (“daylight thief at Amigo’s Café”), the excitement of feeling and watching a storm approach (“dark skies over South Bay”), the feeling of togetherness that arises when being close to human and nonhuman animals, and even trees (“ode to the jack pine”). The philosophical impulse – and presence to all life – is also present in more meditative poems, like “listening to stone” (40-41), where the speaker is stone that is sculpted, where the words allow us to feel the life that rests within stone.

As these titles and others indicate, Bouvier’s poems are firmly set in place, between Île-à-la-Crosse and Saskatoon, among the relatives she names and whose memory she recalls, in the close braiding of words, animate and inanimate life, and emotions. The collection offers repeated occasions for meditating along with Bouvier, following her gaze to what will then grab our own.

Jérôme Melançon writes and teaches and writes and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His third chapbook, Bridges Under the Water, is forthcoming with above/ground press. It follows Tomorrow’s Going to Be Bright (2022) and Coup (2020), as well as his most recent poetry collection, En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He has also published two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016), as well as one book of philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018). He has edited books and journal issues, and keeps publishing academic articles that have nothing to do with any of this. He’s on Twitter mostly, and sometimes on Instagram, both at @lethejerome.