In my life as a reader, Rat Jelly really stands out. I was twenty-four when I first read it, newly-minted as a poet, and newly-arrived in Canada. It was part of the welcoming committee. Welcome to Canada, Ken, and welcome to Canadian Literature.

In memory, I read both Rat Jelly and Coming Through Slaughter in the same year (1975-76). Rat Jelly introduced me to what we would call these days postmodern Canadian poetry,and Coming Through Slaughter introduced me to postmodern Canadian fiction.

I’ve told the tale of how I became a Coach House author in other places. In this essay, I want to mostly talk about what it meant to read Rat Jelly in 1975, and what it means to be rereading it in 2022, on the verge of the fiftieth anniversary of its publication.

In many ways, as a reader, Rat Jelly woke me up. Perhaps I’d been sleepwalking through texts. It was news, and it was new. I’d never encountered a poetry book like it before.

So the real goal of this essay is to “revisit” Rat Jelly. What I want to explore: How does it stand up, and how do I read it now? What is it still offering and giving a reader? To what extent is it still fun to be a pilgrim wandering through this text?

When he was my editor at Coach House, bpNichol taught me that Coach House Press books start at their cover and end at their back cover. Covers don’t have to be mere packaging. Title pages don’t necessarily have to be purely informational. Section dividers don’t necessarily only have to be dividing sections. Everything that a reader encounters in a book can be utilized towards the book’s total effect, and should be.

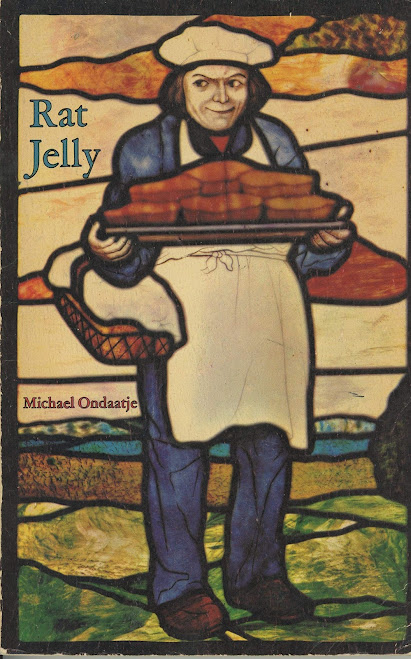

So the first point that I want to make is that, in that era, Coach House Press books were always different from other Canadian commercial and small press books. And, in 1973, Rat Jelly was a Coach House Press book. It was produced with love and attention. Every detail of the book was delved into. And a reader’s engagement with Rat Jelly begins with the cover. That amazing cover.

The pie man. I still adore the stained glass window cover with the pie man. And though he has a tray heaped high with (rat?) jelly tarts, I have always thought of him as “the pie man.” You can tell that he bakes with a real sense of commitment to the mission.

Was this cover my somewhat harsh introduction to The Age of Irony? Undoubtedly. I was a trusting soul. Maybe Ondaatje was telling me not to trust so much. Maybe he was telling me to always pay attention to the eyes of others in all of the various life transactions that would ensue. And maybe he was telling my twenty-four year old consciousness that life wasn’t always or really on the level. Nor was he.

Or maybe he was just having fun. The title of the book, Rat Jelly, is sort of a fun title, but not really. When it all comes down to it, it is an insidious title more than it is a joking title. And the cover image certainly deepens the darkness.

One opens the Coach House Press Rat Jelly to a blue inside cover and a matching blue endpaper. Nice. Blue is for boys, and I love blue. A somewhat different blue will be picked up for the book’s section dividers. But I am getting ahead of myself.

A half title page, and then a title page. The title page states the publishers as “The Coach House Press.” As in “the original” and as in “the one and only.” And we are not getting away from the title (Rat Jelly) anytime soon.

The Contents page divides the book up into three sections: “Families”, “Live Bait”, and “White Dwarfs”. In 2022, we know a lot more about all of these designations or “themes” in Ondaatje’s life’s work. He was thirty when Rat Jelly was published. Now he is almost eighty. At the time I first read the book (1975), I was struck by how the book was divided up into named sections, as opposed to just numbering them (he does this as well later on in Secular Love).

Looking back over the Ondaatje’s career, is there a theme or concern that looms larger in Ondaatje’s work than families? Probably not. It’s there in all the fiction, from Coming Through Slaughter right on down to Warlight. And it’s there is all of the poetry, from The Dainty Monsters through to Handwriting. And let’s not forget Running In The Family.

Then there’s “Live Bait.” Again, in what Ondaatje novel do we not see a character being offered as some version of live bait?

Finally, there’s “White Dwarfs”:

this is for those people

that hover and hover

and die in the ether peripheries

Buddy Bolden. Patrick Lewis. Almasy the English patient. Caravaggio. Etc.

Looking back, one can see Rat Jelly (and its Contents page) as being an encyclopedia of Ondaatje’s writerly concerns.

*

The blue divider of the first section in Rat Jelly, “Families,” features an epigraph from Richard Starks’ The Sour Lemon Store, in which a woman chastises a man (Parker) who is reticent to speak. Her command is ‘Talk to me, Parker, goddammit.’

The first poem in the first section of the book is “War Machine.” Rat Jelly hails from the Vietnam era. I also can’t help but think that Ondaatje has been reading Leonard Cohen’s The Energy of Slaves (1971). The last line, “just listen to the loathing,” proves an odd introduction to Rat Jelly. Is that what we are going to do with this book: listen to the loathing? Happily, the answer is No.

Again, the title of this first section is “Families,’ and we get poems about wife, children, father. A handful of these poems have been persistently anthologized: “Billboards,” Notes for the Legend of Salad Woman,” “Dates,” and of course “Letters & Other Worlds.”

These poems have been repeatedly anthologized because they are among the stronger poems in Rat Jelly and because they embody much of the quirkiness of Ondaatje’s style and subject matter in this book.

“Billboards” is one of those great Ondaatje “conundrum” poems:

My

wife’s problems with husbands, houses,

her

children that I meet

at

stations in Kingston, in Toronto, in London Ontario

--they

come down the grey steps

bright

as actors after their drugged four hour ride

of

spilled orange juice and comics

(when

will they produce a gun and shoot me

at Union

Station by Gate 4?)

Reunions

for Easter egg hunts

kite

flying, Christmases.

They

descend on my shoulders every holiday.

All

this, I was about to say,

disturbs, invades my virgin past.

When I was nineteen, I dated a woman who was twenty-one and who had a four year old daughter. It kind of felt like this.

“With her came the locusts of history—.” Yes, indeed.

Nowadays I somehow get the feeling

I’m in a

complex situation,

one of

several billboard posters

blending

in the rain.

Are the billboard posters husbands? Probably.

The wife dominates his reality in seen and unseen ways.

I am

writing this with a pen my wife has used

to write

a letter to her first husband.

On it is

the smell of her hair.

She must

have placed it down between sentences

and

thought, and driven her fingers round her skull

gathered

the slightest smell of her head

and

brought it back to the pen.

Another quirky wife poem is “Notes for the legend of Salad Woman.” Images of green and gardens predominate. Here is the last stanza:

On our

last day in Eden as we walked out

she

nibbled the leaves at her breast and crotch.

But

there’s none to touch

none to

equal

the

Chlorophyll Kiss

When I was younger I was bowled over by this poem (and by women who loved salads). I still quite like it.

“Dates” is a poem I have taught many times. I still don’t quite have a handle on it. I hear the echoes of Auden’s “In Memory of W.B. Yeats.” And the poem is sort of a fiesta of poetry, invoking Wallace Stevens and his poem “The Well Dressed Man with a Beard” in its second stanza. The third stanza brings together Ondaatje’s mother being pregnant with him and Wallace Stevens engaged in the process of writing a poem, perhaps “The Well Dressed Man with a Beard.” Creation and fecundity. It’s a nice poem to trot out in a Creative Writing class.

“Griffin of the Night” is a small poem, but extremely effective.

I’m

holding my son in my arms

sweating

after nightmares

small me

fingers

in his mouth

small me

sweating after nightmares

The last poem in the “Families” section is “Letters & Other Worlds,” and is probably the most famous Ondaatje poem after “The Cinnamon Peeler.” It’s the first time that readers get to hear about Mervyn Ondaatje, Ondaatje’s father (there will be a lot more about his father in Running in the Family).

The poem is a tour de force of both style and subject matter. It is both intimate and panoramic, which is a hard combination to arrive at. The last stanza of the poem is deservedly famous.

There

speeches, head dreams, apologies,

the

gentle letters were composed.

With the

clarity of architects

he would

write of the row of blue flowers

his new

wife had planted,

the

plans for electricity in the house,

how my

half-sister fell near a snake

and it

had awakened and not touched her.

Letters

in a clear hand of the most complete empathy

his

heart widening and widening and widening

to all

manner of change in his children and friends

while he

himself edged

into the

terrible acute hatred

of his

own privacy

till he

balanced and fell

the

length of his body

the

blood screaming in

the

empty reservoir of bones

the

blood searching in his head without metaphor

After so much off-beat humour about families, the poems about Ondaatje’s son Griffin and his father Mervyn are compelling and astonishing.

*

The second section of Rat Jelly is “Live Bait.” What surprises me, reading the book again in 2022, is that the “Live Bait” section is something of a soft middle in relation to the first and third sections. I don’t remember feeling that way back in 1975. There aren’t really any “anthology pieces” in this section.

The section opens with the poem “Rat Jelly,” which throws down some kind of gauntlet.

See the

rat in the jelly

steaming

dirty hair

frozen,

bring it out on a glass tray

split

the pie four ways and eat

I took

great care cooking this treat for you

and tho

it looks good to yuh

and tho

it smells of the Westinghouse still

and

tastes of exotic fish or

maybe

the expensive arse of a cow

I want

you to know it’s rat

steamy

dirty hair and still alive

(caught

him last sunday

thinking

of the fridge, thinking of you.

In part, the poem takes us back to the cover and to the insidious pie man. But if these are his thoughts. . .the poem remains something of a curiosity. Perhaps its provocation no longer provokes in 2022. Or perhaps I’m an old man reading this now, as opposed to an edgy young man.

This section of the book is certainly pushing against something. Its epigraph is taken from Howard O’Hagan’s Tay John, and concerns itself with words, speaking, lying and the ramifications of utterance.

They found the skull, fallen to the ground

and caught in the black twisted roots of a tree.

The

stone was still between its jaws. Yaada took a stick and pointed.

“See!” she said, “he was a great liar, and the word has choked him!”

For me, the three standout poems in the second section are the two dog poems—“Flirt and Wallace” and “Loop”—and the poem “King Kong.”

Dog poems are almost a sub-genre in Ondaatje’s writing. Dogs abound. “Flirt and Wallace” merits the whole poem being quoted:

The dog

almost

tore my

son’s left eye out

with

love, left a welt of passion

across

his cheek

The

other dog licks

the

armpits of my shirt

for the

salt

the

smell and taste

that

identifies me from others

With

teeth which carry broken birds

with wet

fur jaws that eat snow

suck the

juice from branches

swallowing them all down

leaving

their mouths tasteless, extroverted

they

graze our bodies with their love

The last line suggests what the deal between dogs and humans might be. Maybe this is why dogs accompany humans down through the ages.

The first line of the poem “Loop” promises that it will be “My last dog poem.” That Is a promise Ondaatje simply cannot keep.

I am not a dog person, but I love dogs when I read about them in Ondaatje’s writing. It needs to be said that one of my favourite poetry books of all time is Artie Gold’s some of the cat poems. Maybe poetry is one of the ways I have for interacting with cats and dogs.

Starting with The Dainty Monsters, Ondaatje proves interested in animals and in the animal world.

The poem “Loop” is a celebration of a dog and of the world that dogs inhabit. This dog has lost an eye, but still does all of the things that dogs do.

He

survives the porcupine, cars, poison,

fences

with their spasms of electricity.

Vomits

up bones, bathes at night

in

Holiday Inn swimming pools.

Of Loop, Ondaatje further says that “He is the one you see at Drive-Ins / tearing silent Into garbage / while societies unfold in his sky.”

The poem “King Kong” almost serves as a preamble to the more famous Ondaatje poem “King Kong meets Wallace Stevens,” which is in the third section of Rat Jelly.

In the

yellow dust

of the

light of the National Guard

he

perishes magnanimous

tearing

the world apart.

He

pitches his balls accidentally

through

a 14th storey window

gets a

blow job

from the

vacuum left by jets.

Ondaatje’s poem “King Kong” is a weird retelling of the movie, the movie that I watched eleven times one week as a child on Million Dollar Movie. I really “get” this poem, and its oddball perspective. And its ending makes perfect sense to me.

So we

renew him

capable

in the zoo of night.

As a child, probably the first tragic tears I ever wept were for Kong, shot by the planes and toppled from the Empire State Building. I lived in New York, and Kong died in my city.

*

The third and final section of Rat Jelly is “White Dwarfs.” Among other poems, it contains six of Ondaatje’s most powerful and recognized poems.

The very first poem in the “White Dwarfs” section is the exquisite “We’re at the graveyard.”

Stuart

Sally Kim and I

watching

still stars

or now

and then sliding stars

like

hawk spit to the trees.

Up there

the clear charts,

the

systems’ intricate branches

which

change with hours and solstices,

the bone

geometry of moving from there, to there.

And down

here—friends

whose

minds and bodies

shift

like acrobats to each other.

When we

leave, they move

to an

altitude of silence.

So our

minds shape

and lock

the transient,

parallel

these bats

who

organize the air

with

thick blinks of travel.

Sally is

like grey snow in the grass.

Sally of

the beautiful bones

pregnant

below stars.

Canadian poetry doesn’t get much better than this.

*

If I ever had any doubts about the poems in “White Dwarfs,” they are completely eliminated by the fact of the section’s epigraph being taken from Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man, possibly my favourite novel. Here’s the epigraph:

So

saying, the merchant rose, and making his adieux, left the table with the air

of one

mortified at having been tempted by his own honest goodness, accidentally

stimulated into making mad disclosures—to himself as to another---of the

queer,

unaccountable caprices of his natural heart.

This is great stuff, and enhances the atmosphere of Ondaatje’s own “mad disclosures,” which take the form of poems in this last and final section of Rat Jelly.

“Burning Hills” is a poem that hooked me during my first reading of Rat Jelly back in 1975. It is very much a poet’s poem. I taught it on and off (mostly on) to Creative Writing students for thirty-three years.

So he

came to write again

in the

burnt hill region

north of

Kingston. A cabin

with

mildew spreading down walls.

Bullfrogs on either side of him.

The poem is cinematic, influenced by movies. And it reminds me that movies have always done a lousy job of showing the writer at work. In part, they do a lousy job because they try to present an exterior view of an internal process. Back in the age of smoking there were a lot of stubbed-out cigarettes in the ashtray. And the pounding of typewriter keys. And the crumpling of paper.

I love the particulars of getting organized that Ondaatje presents.

Hanging

his lantern of Shell Vapona Strip

on a

hook in the centre of the room

he

waited a long time. Opened

the

Hilroy writing pad, yellow Bic pen.

Yes, that sounds like the work we prepare to do. For me, it’s a notebook and a different kind of Bic pen, clear and see through. I always get stuck on “a long time,” since my own process doesn’t work like that. But I am quite sympathetic to Ondaatje’s process, and the whole idea of waiting for inspiration.

After this enumeration of process, the poem takes an unusual turn.

Every summer

he believed would be his last.

This

schizophrenic season change, June to September,

when he

deviously thought out plots

across

the character of his friends.

Creative people have a lot of crazy thoughts rattling around in their heads. I don’t know why he believed every summer would be his last, but I believe him. And the idea of writing in the summer, when school is out, and one is no longer on campus and functioning as a professor—I know that one.

For me, the poem gains a lot of its power from the use of the third person. It’s ‘he” not “I”. Though the poet is clearly the narrator.

Embedded in the routine of writing, there’s the fear of writer’s block.

One year

maybe he would come and sit

for 4

months and not write a word down

would

sit and investigate colours, the

insects

in the room with him.

At the age of twenty-four I valued Ondaatje’s admission of the fear that goes hand in hand with writing. And at the age of seventy-one I value it as well. He is revealing his process, and he isn’t concealing anything.

Writers are a superstitious people, like baseball players. They value their routine, and they honour what works. Ondaatje tells us more more about what he brings with him, and how he enhances his environment.

What he

brought: a typewriter

tins of

ginger ale, cigarettes. A copy of StrangeLove,

of The

Intervals, a postcard of Rousseau’s The Dream.

Tools of the trade, refreshment, and those ubiquitous cigarettes. Two books of poetry written by friends for inspiration, and a work of visual art to help with the envisioning.

Having mapped out the preliminaries, Ondaatje dedicates the second half of the poem to an exploration of the actual writing process. This is the part of the poem I have always found invaluable as a writer. It also was an excellent way to introduce creative writing students to what it actually means to write poetry and to be a poet.

Eventually the room was a time machine for him.

He

closed the rotting door, sat down

thought

of pieces of history. The first girl

who in a

park near his school

put a

warm hand into his trousers

unbuttoning and finally catching the spill

across

her wrist, he in the maze of her skirt.

She

later played the piano

when he

had tea with the parents.

He

remembered that surprised—

he had

forgotten for so long.

Under

raincoats in the park on hot days.

Stepping into the time machine, what does the writer, in his aloneness, discover and remember? Moments of sexual intimacy. Using his hands to write, he remembers acts that the hands have performed. He surprises himself, and he surprises the reader too with this.

Everyone knows and understands that writing is a solitary profession. For the first half of the poem we only encounter one individual: this representation of Ondaatje the poet, Ondaatje the writer.

Now, as he begins to write, other people start to appear.

The

summers were layers of civilization in his memory

they

were old photographs he didn’t look at anymore

for

girls in them were chubby not as perfect as in his mind

and his

ungovernable hair was shaved to the edge of skin.

His

friends leaned on bicycles

were 16

and tried to look 21

the

cigarettes too big for their faces.

He could

read those characters easily

undisguised as wedding pictures.

As he’s writing, and smoking cigarettes, he is carried back to the past and the friends smoking cigarettes that are “too big for their faces.”

He could

hardly remember their names

though

they had talked all day, exchanged styles

and like

dogs on a lawn hung around the houses of girls

waiting

for night and the devious sex-games with their simple plots.

Sex a

game of targets, of throwing firecrackers

at a

couple in a field locked in hand-made orgasms,

singing

dramatically in someone’s ear along with the record

‘How

do you think I feel / You know our love’s not real

The one you’re mad about / Is just a

gad-about

How do you think I feel’

He saw all that

complex tension the way his children would.

In his solitude, in his time travel, he is now linked to other people. Male friends, girlfriends, his own children and their dispositions. With distance, he is exploring adolescent sexual intimacy. He’s an adult, looking back at a previous self—Michael Ondaatje at the age of 16, concerned with friends, personal style and yes, “hand-made orgasms.” He recognizes adolescence as a time when human beings are preparing to have sex and are going through the initial explorations, which are often both beautiful and awkward.

The past is contained in photographs, or in images that present themselves as photographs. Is he looking at actual pictures as he writes? Yes, I think so.

There is

one picture that fuses the 5 summers.

Eight of

them are leaning against a wall

arms

around each other

looking

into the camera and the sun

trying

to smile at the unseen adult photographer

trying

against the glare to look 21 and confident.

The

summer and friendship will last forever.

Except

one who was eating an apple. That was him

oblivious to the significance of the moment.

Now he

hungers to have that arm around the next shoulder.

The

wretched apple is fresh and white.

“The wretched apple” is what separates him from his friends and makes him “other.” Apple resonates with knowledge, Garden of Eden. After all of this discussion about adolescent sexuality, this photograph is about friendship, camaraderie, being linked with others and integrated into the group. But, of course, “he” is the writer, the solitary, the isolato, the one who stands alone oblivious to the moment, but, in later years, now is reenacting it, valuing it, hungering for it.

For me, the last stanza encapsulates the whole writing process, as it is meant to.

Since he

began burning hills

the

Shell strip has taken effect.

A wasp

is crawling on the floor

tumbling

over, its motor fanatic.

He has

smoked 5 cigarettes.

He has

written slowly and carefully

with

great love and great coldness.

When he

finishes he will go back

hunting

for the lies that are obvious.

As a young writer, this poem totally instructed me in what was necessary. “Great love and great coldness” nails down the writer’s predicament and the writer’s orientation. The state that the poet needs to achieve. The novelist and short story writer as well.

The last line resonates and echoes. “He” isn’t just hunting for the lies. He is “hunting for the lies that are obvious.” The subtle lies he will let pass. Or so I think that that is what the poem says.

*

For me, “King Kong meets Wallace Stevens” is amusing. It reminds me of Grade Z Japanese horror flicks like King Kong Versus Godzilla and Mothra Versus Godzilla (not so sure the second one exists, but you get my point). In certain light, King Kong looks a little bit like Wallace Stevens, and maybe that is a bit at play in the poem.

It’s another photograph poem:

Take two

photographs—

Wallace

Stevens and King Kong

(Is it

significant that I eat bananas as I write this?)

The poem is a compare and contrast.

Stevens

is portly, benign, a white brush cut

striped

tie. Businessman but

for the

dark thick hands, the naked brain

the

thought in him.

Kong is

staggering

lost in

New York streets again

a spawn

of annoyed cars at his toes.

The mind

is nowhere.

Fingers

are plastic, electric under the skin.

He’s at

the call of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Kong is an imaginary being. Stevens is a poet engaged with the imagination.

Meanwhile W.S. in his suit

is

thinking chaos is thinking fences.

In his

head the seeds of fresh pain

his

exorcising,

the

bellow of locked blood.

The line “is thinking chaos is thinking fences” is quintessential Ondaatje. His imagining of the poet’s consciousness illustrates his own. But the comparison in the poem remains that between Kong and Stevens. A poet and a sympathetic monster from the realms of horror.

The meaning contained in the last two lines eluded me in 1975, and it continues to elude me now.

The

hands drain from his jacket,

pose in

the murderer’s shadow.

Why do I suddenly think of Peter Lorre and Mad Love/The Hands of Orlac? Is he talking about Wallace Stevens, and the hands of Wallace Stevens? Who is the murderer? I wind up with a mind full of questions.

*

‘The gate in his head’ has often been presented as an illustration of Ondaatje’s postmodern poetics. It is dedicated to Victor Coleman, the original Coach House editor (circa 1965-1975).

Victor,

the shy mind

revealing the faint scars

colored

strata of the brain

not

clarity but the sense of shift

I have always found the poem interesting but elusive. For me, as reader, it stays somewhat in realms of abstraction. I can’t quite get a handle on “the shy mind.” I’ll concede that “not clarity but the sense of shift” begins to sound like postmodernism. As does what comes next: “a few lines, the tracks of thought.” The poem continues:

Landscape of busted trees

the

melted tires in the sun

Stan’s

fishbowl

with a

book inside

turning

its pages

like

some sea animal

camouflaging itself

the

typeface clarity

going

slow blonde in the sun full water

There used to be a fishbowl with a book in it at the upstairs offices of Coach House Press. That’s “Stan’s fishbowl,” presumably constructed by Coach House’s owner, Stan Bevington. Early Coach House books used to have a “Printed at Coach House Press by mindless acid freaks” notice on its business page. There isn’t such a notice on the business page of Rat Jelly, but there could have been. The book is postmodern, alternative, drug-influenced, psychedelic.

The next stanza lays some claim to being an expression of Ondaatje’s poetics.

My mind

is pouring chaos

in nets

onto the page.

A blind

lover, don’t know

what I

love until I write it out.

And then

from Gibson’s your letter

with a

blurred photograph of a gull.

Caught

vision. The stunning white bird

an

unclear stir.

“Caught vision” is a good two word definition of a postmodern poem. And here is another photograph, and another poem in Rat Jelly that is built upon a photograph. Why Coleman sends Ondaatje this photograph. . .we don’t quite know. Except that it is “Caught vision.” So maybe that is the reason it is sent. “My mind is pouring chaos / in nets onto the page” is again, perhaps, a definition of poetic process.

The poem concludes

And that

is all this writing should be then.

The

beautiful formed things caught at the wrong moment

so they

are shapeless, awkward

moving

to the clear.

“The beautiful formed things caught at the wrong moment”—it bears repeating.

The poem lays claim to a process and to an aesthetic even, though perhaps it’s as slippery as mercury. And perhaps it is only the aesthetic for this poem, not the entire collection. For this poem, it works.

*

The poem “Spider Blues” is either a strange success or a beautiful failure. It reminds me a lot of Herman Melville, who wasn’t afraid to try something elaborate. It’s a poem with large scope and intriguing moves.

The poem dives into compelling territory right from the outset.

My wife

has a smell that spiders go for.

At night

they descend saliva roads

down to

her dreaming body.

They are

magnetized by her breath’s rhythm,

leave

their own constructions

for

succulent travel across her face and shoulder.

My own

devious nightmares

are

struck to death by her shrieks.

What is going on here? The proposition of the poem, as set out in the first line, is engaging, somewhat appalling, somewhat fascinating. The poem proceeds in an atmosphere of horror film. A woman, attracting spiders to her by scent, a sleeping woman, a sleeping partner, and an atmosphere shattered by “her shrieks.” Hitchcock yes, but maybe more William Castle.

Ondaatje now dives into the spiders, who they are and what they mean.

About

the spiders.

Having

once tried to play piano

and

unable to keep both hands

segregated in their intent

I admire

the spider, his control classic

his

eight legs finicky,

making

lines out of juice in his abdomen.

The reader notes that the spider is a “he,” and that the poet speaking “admires” the way that the spider creates “lines” (like the poet) which are strands of the spider web (poem?).

A kind

of writer I suppose.

He

thinks a path and travels

the

emptiness that was there

leaves

his bridge behind

looking

back saying Jeez

did I do

that?

and uses

his ending

to

swivel to new regions

where

the raw of feelings exist.

Is Ondaatje talking about writers or spiders, or both?

Spiders

like poets are obsessed with power.

They

write their murderous art which sleeps

like

stars in the corner of rooms,

a mouth

to catch audiences

weak broken sick

Spiders—spider webs—flies.

Poets—poems—audience.

And

spider comes to fly, says

Love me

I can kill you, love me

my

intelligence has run rings about you

love me,

I kill you for the clarity that

comes

when roads I make are being made

love me,

antisocial, lovely.

Spiders kill flies for food. This spider sounds more like a poet.

And fly

says, O no

no your

analogies are slipping

no I

choose who I die with

you

spider poets are all the same

At the time of the poem’s writing, the insignia of House of Anansi Press was Anansi, the spider. And Ondaatje was a “spider poet,” having published The Collected Works of Billy the Kid with House of Anansi.

you in

your close vanity of making,

you

minor drag, your saliva stars always

soaking

up the liquid from our atmosphere.

And the

spider in his loathing

crucifies his victim in his spit

making

them the art he cannot be.

In Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, F. tells I. not to be a magician, but to be magic. There is maybe an echo of that in this (Ondaatje wrote a critical monograph about Cohen and his work). I can’t decide if the poem is trying too hard at this juncture, or whether Ondaatje manages to nail down his point. I note that the word “loathing” from the poem “War Machine” is making a reappearance here.

Does the dead fly become the art the spider “cannot be”? That is left for every individual reader to decide. In a way the poem hits a wall here, needs to shift gears in order to proceed any further. And does.

So. The

ending we must arrive at.

ok folks.

Nightmare for my wife and me.

Why must the poem end in nightmare? Isn’t that a choice the poet is making? Is it the inevitable choice? Is it what the poem demands? Is it what the reader demands? That’s the reader in me, raising questions. The writer in me knows that, of course, the poem needs to end in nightmare.

It was a

large white room

and the

spiders had thrown

their

scaffolds off the floor

onto four walls and the ceiling.

They had

surpassed themselves this time

and with

the white roads

their

eight legs built with speed

they

carried her up—her whole body

into the

dreaming air so gently

she did

not wake or scream.

The strands of web are now “roads,” and the spiders do their work in relative silence, carrying up Ondaatje’s sleeping, undisturbed wife.

What a

scene. So many trails

the room

was a shattered pane of glass.

Everybody clapped, all the flies.

The flies are applauding the artistry of the spiders. In this instance, it does not involve them. The spiders are inflicting their artistry upon the human.

They

came and gasped, all

everybody cried at the beauty

ALL

except

the working black architects

and the

lady locked in their dream their

theme

The poem has to end, and this is how it ends. Is it too compact or tidy? Maybe. Every reader needs to decide. The reader is left with work to do.

*

The last poem in Rat Jelly is “White Dwarfs,” and it is well-covered territory. The perspective of the poem has given birth to key works of Ondaatje’s fiction: Coming Through Slaughter, In the Skin of a Lion, The English Patient. It isn’t that the poem is dated or uninteresting. It has merely been eclipsed by the fiction. It’s been expanded upon, at length.

*

As a reader, Rat Jelly blew me away when I read it in 1975. In 2022 (and 2023), it still possesses a compelling power. And it’s fun. Long may it run.

Toronto

June—August 2022

Ken Norris was born in New York City in 1951. He came to Canada in the early 1970s, to escape Nixon-era America and to pursue his graduate education. He completed an M.A. at Concordia University and a Ph.D. in Canadian Literature at McGill University. He became a Canadian citizen in 1985. For thirty-three years he taught Canadian Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Maine. He currently resides in Toronto.