The 'process notes' pieces were originally solicited by Maw Shein Win as addendum to her teaching particular poems and poetry collections for various workshops and classes. These poems and process note by James Cagney was part of her curriculum for her Poetry Workshop at University of San Francisco in their MFA Program for Spring semester of 2023. https://www.usfca.edu/arts-sciences/programs/graduate/writing-mfa

One of the people whose presence is strongly felt in my second poetry collection, MARTIAN: The Saint Of Loneliness, is my friend, Sekou. His is the longest friendship I’ve had, and he died early during the pandemic from Sickle Cell, not COVID. The worst thought I’ve ever entertained is a kind of gratitude that he did not have to endure any emergency hospital visits behind Sickle Cell crises during the mandatory stay-at-home order. Much of our friendship, and in turn, a great part of his life was spent shuttling back and forth to hospitals and being under care. So common were his episodes, I learned that if we hadn’t talked on the phone in a while, I should just go directly to the hospital after work and ask if he was checked in as a patient. And no exaggeration: 8 times out of 10 he’d be there, and surprised to see me walk through the door.

For several years, I worked as an in-home care provider to my mother who was dying of an asbestos-related lung disease. I was an awful maid who gave good injections. A nurse who mopped floors and did laundry. I couldn’t drive. But I could do whatever she needed when she couldn’t do anything. I held great empathy (and exhaustion) for people victimized by their own bodies, by things beyond their control.

Sekou and I met via poetry open mics in Oakland. He was the older brother to another performer I also knew and loved. He was a poet who would often improvise stories as a way of negotiating continuous body pain. Sometimes he would attend an open mic and go straight to the hospital afterwards. Over the years, his diligence often introduced me to poetry and storytelling series that I didn’t know existed.

His life, in many ways, was lonelier than my own. If I felt trapped due to loyalty and love to my dying mother, he was trapped by his own body and its random choices. If I could sit in a crowded room of poets and feel hollow and lonely, much of his time was spent in hospital rooms assuaged by his Walkman or Smartphone or his brother or father visiting to read to him. I would visit and monologue about whatever adventures I’d been having, or listen to him talk about the stories he’d been thinking or lucid dreaming. Storytelling was a numbing agent and distraction for whatever was broiling beneath his skin.

Usually, he would be sent to what we called Pill Hill in Oakland, and the major hospital on its highest hilltop. Over my life, every relative I have had entered its sliding door and was never heard from again. I didn’t enjoy the aroma of hospitals nor visiting them any more than anyone else. I knew what it felt being there for an extended period. The noises, the temperature, the food, the smell. All of it, queasy and discomforting and lonely, lonely, lonely.

One weekend, I attended an outdoor poetry reading at Mosswood Park, next door to the hospital. It was a good event with many solid readers. After it adjourned, I walked up the hill to the hospital, unannounced. I found him as usual in a single room, bedridden beneath a huge bay window. His bed trafficked in devices and cords: phones, headsets, Game Boys. Between himself and his brother, I was a mysterious third son in their family. I knew his mother’s cheery voice in the background and knew of his legendary father, whom I’m not sure I was ever in the same room with more than twice. I came in and Sekou immediately wanted to go for a walk. Grabbing his IV pole and monitor, he slowly poured from the bed, and we did a lap around the hospital floor. I’d sit through nurse visits. I’d sit through his meals, and no matter how many hospital visits I’d make or to whom, all the food smelled the same. No wonder my father wanted to kill the ‘man’ whom he described as the Soup Making S.O.B. downstairs. I’ve sat through a couple of doctor visits and would leave after he received meds that quickly led to sleep.

When we got back to his room, he asked me to read some poems, then he would share whatever new story he’d been developing. I’d stay a couple of hours and as the sun dipped, so would I.

That visit after the poetry reading in the park was one of the last I ever made. As I got to the door, he asked me for a hug. Truth be told, I don’t remember that happening a lot. We'd leave with a handshake, a pound. Or maybe we hugged often, and I’ve lost that detail. Perhaps the last time stands out because it was the last time. I let the door go and went back to him, as he negotiated off the bed.

I have been complimented for my hugs and assume my arms safe, grounded, and healing—because for the most part that’s how I feel when hugging someone. I’ve often been asked for a second hug. I’ve often lingered in a person’s arms not wanting to be the first to let go. It’s such a simple thing, hugging. And so important. An event I like being asked for. But I’ve never been present minded enough to write about it. What does one say about hugging? What would E.E. Cummings say? Or Langston Hughes?

That night in bed he appeared ridiculously tiny, the child version of himself or as if I were seeing him from a full block away. With us embracing, I became fully present in his hospital room. It appeared sterile and metallic, glaring white with steel bars framing the bed, the window, the TV monitor, the dinner tray, the hospital machinery. He was the sole color and main object in the room, and I thought of those gorgeous and singular beta fish with their multicolored fins, like long, flowing ribbons. The water they floated in could be isopropyl alcohol for all I knew.

HUG

Both visiting days he asked for this

his prophetic eyes, body

a Catherine wheel going nova:

first, vaulting off the parallel bars of his walker

next, holy ghost dismounting the bed

a 10-point landing on the terrace

of my chest.

In the agreed upon silence of my arms

he felt fractional.

His spine floated, over-cooked

beneath his skin.

We whispered

as

if healing

were a current

directed by harmonized wavelets

of breath.

Anyone watching might’ve expected

us to kiss

since we appeared to eclipse something.

Pulling open the door,

I turned.

How quiet and humble he looked.

Hollow,

drowsy as a toddler.

The room glittered,

a stainless steel fish-tank.

He, a betta crown-tailed by illness.

Seeing him centered

floating

gulping air

like that.

***

I seemed to remember he’d had major surgery on his hip. I can’t write confidently that he’d already had it (I think so) because I can’t justify describing someone getting out of a hospital bed without use of a hip. Is that possible? What I will say is it was a hug I remembered because within my arms, his body felt weird. Gelatinous and fractured within like he was a dropped toy. I held him but not as tightly as I usually would. And during my long walk to the elevator, then the bus stop, that hug remained within and haunted me until I wrote it out in words.

I wrote of him again in another poem in

my book, MARTIAN: The Saint of Loneliness,

in a poem called “During The Parade.” I committed myself to converting all my

dreams into poems, but that isn’t always appropriate. The dream was vivid. The

colors of the confetti, the texture of the ground. The emotion I felt. I don’t

remember dreaming of him very much over the years, before or after. But that

dream, I felt, deserved to be captured. Its quiet imagery wouldn’t leave me

alone.

DURING

THE PARADE

It was startling to see you

staring out from a touchpad

on the ground.

Your mouth’s silent cloud.

You blinked bewildered

a patient newscaster.

You appeared engaged

even as people stepped over

you, and confetti misted.

I wept, picking up the screen.

How'd you get here, I asked.

My mom dropped me off, you said.

You smiled. You wore a 1950s

fedora. You looked nice.

I scanned the crowd for your mother

but it blurred with strangers. I

wondered

if she was somewhere drunk and

relieved.

I held you like an empty plate.

I couldn't look in your face.

I wanted to position you

up high somewhere

so you could see everything.

But you only asked me

to hold you

****

The process of writing poems or

assembling a book all seems the same. It's creatively listening, intuitively

listening to one’s self, and how that self operates within the world. What that

self sees, feels, experiences—and sharing that report in the barest more

beautiful language available. I don’t know how to instruct one to pay attention

to the voices, the impulses. Some voices can be negative, some impulses

self-destructive. But the main thing is to pay attention. I could have shrugged

off the dream, or dismissed hugging my friend as ‘an everyday thing’ and moved

on. But everyday things often hold tremendous weight depending upon how you

engage them. That’s the purpose and value of poetry, right? Acknowledging the

weight of everyday things. I never expected my friend to appear so distinctly

within a poem, much less my book- a book published the year after his passing.

I felt self-conscious about sharing those poems with him and his family, but eventually I did. I felt self-conscious because they’re so personal, so close. It's him and I hugging, dreaming together and me dropping a microphone between our chests so you can listen to the conversation beating between our hearts. Where and who are you in all this?

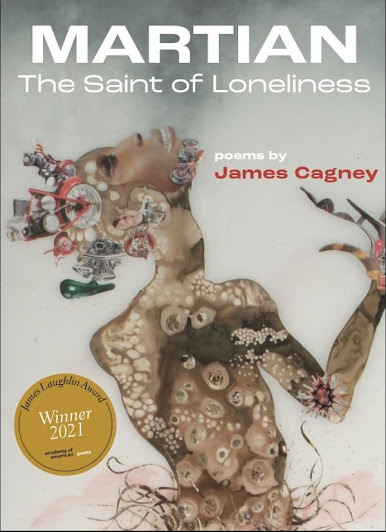

James Cagney’s second poetry collection, Martian: The Saint of Loneliness is the winner of the 2021 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. His first, Black Steel Magnolias In The Hour Of Chaos Theory won the PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award in 2018. Both titles are available from Nomadic Press. For more information, please visit JamesCagneypoet.com

Maw Shein Win's recent poetry book is Storage Unit for the Spirit House (Omnidawn), which was nominated for the Northern California Book Award in Poetry, longlisted for the PEN America Open Book Award, and shortlisted for the California Independent Booksellers Alliance's Golden Poppy Award for Poetry. D.A. Powell wrote of it, "Poetry has long been a vessel, a container of history, emotion, perceptions, keepsakes. This piercing, gorgeous collection stands both inside and outside of containment: the porcelain vase of stargazer lilies is considered alongside the galley convicts, the children sleeping on the cement floors of detention cells, the nats inside their spirit houses; the spirit houses inside their storage units.…These poems are portals to other worlds and to our own, a space in which one sees and one is seen. A marvelous, timely, and resilient book." Win's previous collections include Invisible Gifts (Manic D Press); her chapbooks include Ruins of a glittering palace (SPA) and Score and Bone (Nomadic Press). Win’s Process Note Series on periodicities : a journal of poetry and poetics features poets and their process. She is the inaugural poet laureate of El Cerrito and often collaborates with visual artists, musicians, and other writers. mawsheinwin.com