It was late at night the first time I arrived in Cuba. It was January, 2003, and my wife had signed up for an educational tour. I decided to tag along. The flight out of Montreal had been delayed and it was 1 a.m. when we deplaned. But the hotel bus was still waiting for us. We loaded our luggage and drove off into a night full of potholes. Sugarcane fires burned in the fields, but there was little lighting on the roads.

And then, a lot of light. A police barricade, with flashing lights, police cars, and in the shadows, a military vehicle. Not a jeep, but more like a troop carrier. And in the ditches, some young men running. I remember one of them had a red bandana on his head. Someone was yelling. We waited, but after a short conversation with the driver, we were waved on through. Tourists.

We were there for ten days. My wife had a salutary schedule of schools, medical facilities, cooperative farms and a residence for children rescued from Chernobyl. I poked along the long beaches east of Havana, avoiding dead jellyfish and resting at the many little open-air mojito bars. Both of us loved it, albeit for different reasons, and we returned several times.

Well, that relationship failed, and so did my enchantment with Cuba. Although I returned on my own and, later on, with my new family, it was never quite the same. The seeds of disillusion are there, in the poems of cuba A book: the spalling concrete, the dengue fever, the classic cars held together with wire, and mostly, the young soldiers with machine-pistols on many of the corners. I had befriended a couple of young musicians, and knew some people at the natural history museum, but it began to feel that my presence brought police attention in its wake. I haven’t gone back now for almost a decade.

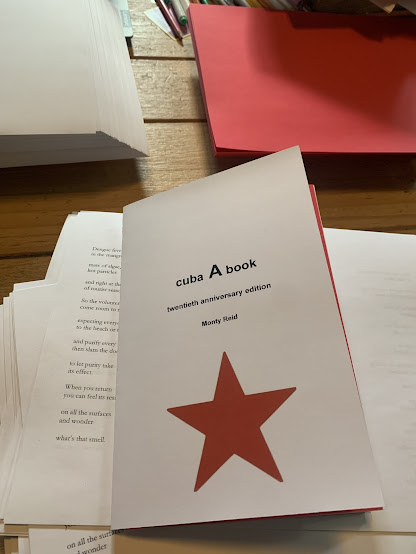

But Cuba did get me writing again, after an extended quiet period. The poems in cuba A book got revised and expanded in Disappointment Island (Chaudiere Books, 2006) and also led me to the work in El Big Zoo, a hybrid project with artist Suzanne Hill. A mistranslation of Nicolas Guillen’s, El gran Zoo, one of my favorite books of Cuban poetry, it remains unpublished in book form, but has shown up in several galleries and various literary magazines and still gets regularly updated. So this little chapbook, which rob coaxed out of me 20 years ago (really??) was important for me. The only thing I didn’t like about it was the star on the cover. It was supposed to be like the star on Che’s famous beret; we fixed it this time.

As I write this, deep in a Canadian winter, Cuba has lost power. The grid has failed and even Havana, usually the last to go, has gone black. The Soviet-built electrical infrastructure is aging and difficult to maintain. It runs on oil, but the main suppliers, Venezuela and Russia, are otherwise occupied, and have reduced shipments. There have been periodic blackouts in the countryside for many years but when Havana, the capital, goes black, you know there’s a serious problem. I hope it’s not beyond fixing.

Monty Reid

2025

Monty Reid was born in Saskatchewan, and currently lives in Ottawa. He is the author of the full-length collections Karst Means Stone (NeWest Press, 1979), The Life of Ryley (Thistledown Press, 1981), The Dream of Snowy Owls (Longspoon Press, 1983), The Alternate Guide (Red Deer College Press, 1985), These Lawns (Red Deer College Press, 1990), Dog Sleeps: Irritated Texts (NeWest Press, 1993), Crawlspace: New and Selected Poems (House of Anansi Press, 1993), Flat Side (Red Deer College Press, 1998), Disappointment Island (Chaudiere Books, 2006), Luskville Reductions (Brick Books, 2008), Garden (Chaudiere Books, 2014) and Meditatio Placentae (Brick Books, 2016). The former Managing Editor of Arc Poetry Magazine, he was the Artistic Director of VERSeFest: Ottawa’s International Poetry Festival for more than a decade.

.jpg)