|

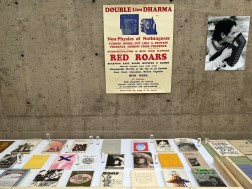

| McClure retrospective

display arranged by City Lights Books, 18 Sept. 2021 |

I

was fortunate to have Michael McClure as one of my first poetry teachers. David

Meltzer’s zestful book of interviews, The San Francisco Poets (1971) was

a helpful guide for when I signed up for poetry workshops at Naropa, as I

quickly checked Michael’s name on the list of offerings.

My

first impression of this “prince

of the San Francisco scene” was his jousting verbally with Lawrence

Ferlinghetti at the opening ceremony of the 25th anniversary On The Road conference

at Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. It was affectionately

dubbed by its participants “Camp Kerouac.”

Allen

Ginsberg was at the podium, making introductions and setting the tone for the

week ahead. “If you brought drugs or psychedelics, take them,” he urged us.

The

message was: even in 1982, with Reagan President, we weren’t going to let it tie

our spirits down or keep us from dreaming.

From

the audience, Ferlinghetti touted the need for the artist to be engagé with the issues of their day,

prompting McClure to counter that without a foregrounding of the environment,

that human life, and politics, were doomed.

“Hundreds

of known species became extinct in the last year, and thousands more will

follow if we don’t act to protect the environment. Biology will have the last

word; if we fail today, we may be gone tomorrow” was the gist of it (my notes are

in my head).

Many

are the times I subsequently encountered Michael. In the winter following Camp

Kerouac, he gave a reading at the University of Chicago.

Spotting

my Naropa t-shirt, he recalled the joys of that conference, and at a student

after-party invited me to join his workshop the next day at the Art Institute

of Chicago.

When

I told him of my plan to move that summer to San Francisco, he encouraged me to

contact him via City Lights. His reply to my arrival missive was an invitation

to his reading at the Palace of Fine Arts in support of Nicaragua (with

Ferlinghetti, Alice Walker, Ernesto Cardenal, and others) in opposition to

Reagan’s U.S.-backed Contra insurgency.

“None

of my poems is about Nicaragua,” he admitted, but on this day he stood against neo-colonial

interventions in Central America.

My

first San Francisco apartment was in the lower Haight; Michael lived on Downey

St., not far from Haight-Ashbury, up the hill from me. I visited him there once,

and he came to my apt tempted by the lure of books, which I have always

surrounded myself with in abundance.

On

an early weekend in January 1984, we tooled around the City in his car,

careening over the Twin Peaks with the manuscript of his new play Vktms that he was ready to post to his

agent. He did not trust the post office in the Haight which was rumored to be

staffed by ’60s burnouts.

Besides

seeing him at readings, we had a number of pleasant chance encounters over

the years. At the Clarion Café on Mission St., I happened upon a joined a

small group at his table as he shared his critiques of two then-popular theater

personalities: Spaulding Gray (the monologist, whose minimal staging centered

on the performer seated at a desk) and George Coates (whose multimedia shows

were visually arresting, flashing light-enhanced spectacles).

Both

were drawing appreciative audiences. After seeing a couple of Coates’ shows, I

shared Michael’s view that they were a triumph of strobing form over substance.

Soon

after I began work in the UC Berkeley Library, Michael sought my help obtaining

early books on Custer. When he returned them, I saw, and gently chided him for

leaving his light pencil marks annotating passages of interest. I wondered if

he was going to give the Boy General a memorable stage treatment akin to his

notorious play The Beard featuring Billy the Kid and Jean Harlow in

Hell, but if that seed germinated, I have not yet read it.

Michael’s

second book of poems was For Artaud (1959). In this regard, he connected

me with an avant garde performance documentarian named Kush, who I recalled

seeing on the streets of Boulder during Camp Kerouac. With much spit flying, Kush

acted out the death of Edgar Allan Poe.

According

to Michael, Kush possessed a recording of Antonin Artaud’s suppressed radio

performance To Have Done With The Judgment of God, which I was eager to

listen to. I found Kush at a large anarchist commune called the Farm, and he agreeably

shared this recording.

One

of my Library colleagues, Richard Ogar, had the blessed good fortune to meet

the love of his life, Leah, at one of Michael’s poetry readings in Berkeley,

and their courtship was attended at various gatherings in Michael’s

performative company.

In

October 2014, I hosted a Litquake/Bancroft Library event marking 30 years from

the approximate death of Richard Brautigan by his own hand in Bolinas. McClure

was a close friend of Brautigan, and was joined in this discussion by daughter

Ianthe, Joanne Kyger, David Meltzer, Robert Hass, Ishmael Reed, Herbert Gold,

V. Vale, and others.

When

someone leaves before their time—and for poets, musicians, and storytellers,

it’s almost always too soon—those who remain have to fill in the gaps.

My

first meeting with Amy was an evening that Michael took her and some of his

students to a show at one of Berkeley’s fine theatres, either Berkeley Rep or

the Aurora Theatre, in the early ots (00-s).

After

Bancroft Library acquired Michael’s literary archive, the Library commissioned

Amy to make a homuncular sculpture of Menches the village scribe or komogrammateus.

This

ca. 119 BCE figure greets visitors to the suite of offices for the Center For

Tebtunis Papyri where Egyptian text fragments are studied by scholars from

around the world.

The

source of these papyri was in large measure mummified crocodiles, domestic

pets, and people—all revered enough by the living to be wrapped in these

lineaments of desire for eternity, which are now enjoying a text-centric

afterlife elucidated by scholars.

In

describing the vast and varied holdings of The Bancroft Library, its late

curator of Rare Books and Literary Manuscripts, Anthony Bliss, liked to remark

that it ranges from Pharaohs to Beat poets.

He

might almost have been talking about Amy’s and Michael’s works in plotting that

continuum.

|

Menches

Komogrammateus [village scribe] of Tebtunis, circa 119 BC, conceived

and sculpted by Amy Evans McClure, 2008 |

People who wear black are in mourning for themselves.

—Michael McClure (October 20, 1932 – May 4,

2020)

Michael

provided many quotable sayings (above his paraphrasing Chekhov) that were

repeated at the in-person memorial in September 2021. Even after three

bicoastal memorials over Zoom marking the anniversary of his passing in May

2020, Amy McClure recognized that Michael’s many friends would not be satisfied

until there was an in-person gathering.

A

strict proof of vaccination requirement, masking, social distancing at the

outdoor CalShakes Theatre in Orinda provided the relatively safe space for that

to happen. 250 or more people attended, and many stories, tears, songs, poems

and laughter were shared.

|

| Amy Evans McClure at

the CalShakes Theatre, 18 September 2021 |

One

story I’ll propagate came from Juvenal Acosta, who was Michael’s department

chair at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Michael had told him of an

early visit to Big Sur, in which he had visited Henry Miller around the time

described in Miller’s Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch (1957).

On

meeting Miller’s wife, Eve McClure (married to Miller 1953-1960), Michael

chatted her up over their shared McClure ancestry.

She

was 4 years older than Michael and 37 years younger than Henry. It wasn’t long

before Henry Miller was ready to boot out the dashing and beautiful upstart he

believed was making moves on his wife.

“You

are a supercilious young man,” he pointed an angry finger in the young poet’s

face.

Michael

was perplexed, having never before heard that word applied to him, and not

knowing exactly what it meant.

Ferlinghetti,

also present, and hosting McClure at his cabin just up the road, was quick to

reassure the elder bohemian that it was all a misunderstanding, and thus Michael

was saved from being thrown out into the night.

As

my literary perambulations recently took me south of Monterey/Carmel, my

research fixed upon a sound recording Allen Ginsberg made with Michael on one

of their later trips to Big Sur. This recording is in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s

papers, also at The Bancroft Library.

The

year was 1966. The three poets had taken acid, Michael played autoharp, with

Allen chanting ommmm in Ferlinghetti’s Bixby Canyon cabin.

The

sound quality is poor, but I manage to make out Michael’s quip: “sounds like anger,

wisdom, joy, nature. And nature was a one-line poem.” After an artful

pause, he adds: “It sure doesn’t lack

stature.”

They

all laugh. A child then approaches—it might have been Ferlinghetti’s or

McClure’s—the recording includes many sounds of family, the rituals of domestic

life, going on in the background.

In

this moment, captured for eternity: a

child offering enchiladas.

D.S. Black is an archives whisperer by day, and somnobiographer

of night. His first major collection of poems, Red Shift Blues, awaits a

publisher. He was born in Toronto, raised there and in Manitoba, and for much

of his adult life has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area of California.