AJ Dolman’s (they/she) debut poetry book is Crazy / Mad (Gordon Hill Press, spring 2024). A professional editor, Dolman is also the author of Lost Enough: A collection of short stories, and three poetry chapbooks, and co-edited Motherhood in Precarious Times (Demeter Press, 2018). Their poetry, fiction and essays have appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, recently including Canthius, Arc Poetry Magazine, QT Literary Magazine, and The Quarantine Review. They are a bi/pan+ rights advocate living on unceded Anishinabe Algonquin territory.

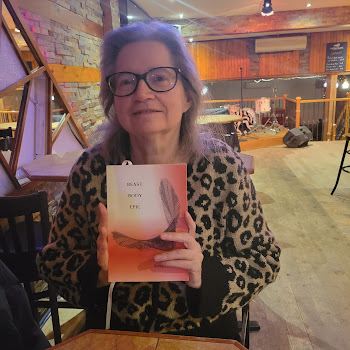

AJ Dolman reads in Ottawa on Sunday, March 24, 2024 as part of VERSeFest 2024.

Amanda Earl: Crazy/Mad is full of puns, and language play: alliteration, assonance, nouns turned into verbs, unique collectives such as “a sorrow of stones.” You have a poem for John Lavery, who was an ingenious word worker. Can you talk about your love of sound and word play? Was your first language Dutch? How does the knowledge of other languages affect your English play with words and sound? Would you like to say more about Lavery?

AJ Dolman: John Lavery was indeed a genius at language and I miss him, and the thrill of reading new writing by him, terribly. We didn’t always agree, but we respected each other, and he never let me off the hook, always prompting me with “So, what are you working on now?” He was able to blend French and English colloquial language into a joyous whirlwind of syllables that sounded perfectly right in its wrongness, boldly direct in its meaningful meaninglessness. He was one of those writers who could simultaneously do the thing (such as writing what was ostensibly cop fiction) while utterly subverting the thing, playing both ends to the middle, as it were. I learned a lot from him, but mostly that we are all allowed to play with these toys of trope, language, genre, sound, meaning.

And yes, my first language was Dutch, my parents and two sisters having immigrated to Canada 14 years before I was born. I was a shy kid, and starting school in a language I barely spoke didn't help that. But the Swiss immigrant kid in our class (Fabienne, still one of my best friends) and I became friends, and she and I muddled along in a sort of made-up Swiss-German/Dutch/English hybrid of language and gestures until we could fully make sense of ourselves and others fully in English.

My Mam was my way into a passion for language, for how intensely its rhythms could be played. There’s always been a sense in my family that my mother could have been a great writer if her circumstances in life had been different. She told the best (also worst) bedtime stories, because she would fully embody the characters, so every witch or wolf scared the life out of me. She was also an alcoholic, as was my Dad. Years later (she got sober when I was a teen, and stayed that way the rest of her life), my mother easily admitted she’d been terrible at parenting. But she certainly was a great language and drama teacher to me.

AE: You dedicate the book, not to one specific person but “to the worried, the lost, the uncertain and the afraid.” Throughout the book, you address issues of social justice through the lens of mental health issues. Those who deal with mental health issues are more often than not erased, harmed by a system that wishes they didn't exist and marginalized. You write about the issues of labour, poverty, sexual orientation, gender, racism and colonialization. At some point in my inculcation into the writing of literary work, I got the idea that one wasn't supposed to write overtly about such issues. Did you also have that impression and how did you override it in order to write and share poems, such as "Delusions of grandeur?"

AJD: The Canadian poetry (and fiction, for that matter) that I first encountered, and that was esteemed by those guarding the CanLit towers when I arrived at its gardens definitely had a silencing effect. It was those quiet examples of “this is what we write about here,” which an emerging writer can easily interpret as “nothing else will be accepted.”

There were exceptions, of course (one of my favourite older books of Canadian poetry is 1978's The Ghosts Call You Poor by Andrew Suknaski, a mad prairie poet I didn't discover until my 30s). But most examples I saw came from the States—Ginsberg, Clifton, poets who were queer and/or Black and/or stemming from poverty, and who were angry out loud.

I was taught to be quiet. Children were to be seen and not heard, and me having first an accent, then secrets of gender and orientation, I doubled down on being quiet. When I was ready to not be as quiet anymore, as an adult, a student, a writer, I was told “We don’t publish political poetry” and “Your message is too overt; stick to metaphor.” Don’t get me wrong, I love a juicy metaphor. But if not right now, in every way we can, then when and how is the best way to declare what we have seen, and to demand better for ourselves and others?

I didn’t trust my own voice for a long time, and repeatedly being told by editors turning down my work that my writing conveyed “a strong voice” felt like being punched in the gut with a silk glove, a surface nicety that did nothing to mask the jab. Yet, audiences and readers seemed to appreciate what I was doing. And I saw more and more people, often from far harsher backgrounds and with more intersecting identities than me, being brave. So, what right, then, do I have to not try to be louder, to be braver, if I can? For myself, but also for others.

AE: While there are glimpses of joy in parental-child relationships, such as in “Inversion,” where you show a child’s humour and intelligence, your poems are unflinchingly candid on the physical and emotional trauma of giving birth and of being a mother, such as in “Perinatal panic disorder” where you write “children a choice you can’t undo,/like suicide.” Or in “Female rage,” where you write about Clytemnestra: “death in masses/of children,/stopping up/a rampant womb that’s yielded/crops of babies.”

You include a poem about Andrea Yates, who drowned her five children. What made you want to openly depict the struggles of motherhood?

AJD: No one in my poems rages against their children themselves. What they rage against is lack of agency. And, I don't, in any way, mean to speak for any other parents or their experiences.

I adore my kid. He’s a teen now, and I have loved being part of his life and his learning and growth. But, everything about pregnancy, birth, and especially the first several years of his life, was immensely traumatic for me. Part of that, in retrospect, had to do with gender dysphoria, though I didn’t realize what it was at the time. Part of it was going into the decision to have a child while mentally ill, which for me came with decisions about medication, with guilt in advance about the poor parent I thought I might be, with concerns around heredity, etc.

As for Yates, I watched documentaries and read numerous articles about Andrea Yates after the she was found to have killed her children, all of whom were still little, one only six months. Yates was ultimately diagnosed afterwards with severe postpartum depression, schizophrenia and postpartum psychosis. What happened was horrific. Yet, what, in the aftermath, makes it still harder to wrap our minds around is the questions around her intent, let alone her capacity for rational thought. People in her life swear Yates never hated her kids. It seems she loved them deeply, and what happened was a horrific confluence of severe mental illness, her having been victimized her entire life, and her religious beliefs leading her to decide she could protect her children from some greater harm awaiting them in their futures by killing them and, thereby, sending them safely to her god to lovingly care for instead.

I used to think my fascination with the story was from seeing it as a worst case scenario for mental illness and parenting. But I realized at some point that what I was most consumed with was that, even in extreme madness, she behaved like so many other people, by responding to her own lack of agency by taking away agency from others. It's not what she consciously decided (she was found insane on retrial, and thus not criminally responsible for her actions), but it was the end result of what she did. And we see that same behaviour, in people technically sane (technically, because, for example, I cannot imagine anyone "sane" believing they can and should own another human being), time and again throughout history.

AE: You deal with mental health issues in this book in a way I rarely read in contemporary poetry. Can you talk about how the collection came together and how you decided to center it around this theme?AJD: I write what I am passionate about, and this is a thread that has run through my life, through generations of my family, among friends and colleagues. And now, especially since the start of the COVID pandemic and general acknowledgement of the climate crisis, anxiety and depression, in particular, seem to be running rampant. Of course they are. Look at what is happening. I am honestly amazed we aren't all just breaking down in the streets daily. Yet, Madness was one of my most fundamental fears for as long as I can remember. Not the being Mad itself, but to be considered crazy, to be sent away, institutionalized, diagnosed. Voicelessness, again.

So, that thread ran through many of my poems, too. And I’ve talked before about the impact Jon Crispin’s photographs of the confiscated luggage of patients of the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane in Upstate New York had on my view of madness as a viable subject. Being invited by guest editor (and absolutely brilliant poet) Roxanna Bennett to contribute fiction to a Matrix issue on Madness also helped me feel this was a topic I could make work for an entire book. As for the actual structuring, some great fellow poets and editors, including Deanna Young and Stuart Ross, looked at previous versions of the collection, and provided great guidance that helped me make both the poems and the book's structure more cohesive. But, it wasn’t until Shane Nielson at Gordon Hill Press pushed me to make the book more what it already almost was by then that I fully embraced it. I am delighted by the end result in a way I ‘think I could have anticipated.

AE: Your portraits of the prairies and the suburbs is full of Gothic landscapes and scenes of horror. Can you talk about influences? Where does your sense of the Gothic and of horror come from?

AJD: Between the ages of two and 15, I grew up on a hog farm in Alice Munro country, Wingham, a foundry town in Huron county, southwestern Ontario. In the early 80s, the bottom dropped out of the hog market and desperation ran through the communities like a rush of Crown Royal. It suddenly cost more to raise a hog than you would ever make on it per pound. But who would buy your farm? Eventually, the banks refused to even foreclose on any more properties. They were holding too many absolutely unsellable farms already. So you couldn’t even claim bankruptcy. You could just go deeper and deeper into debt, with no hope for you or your family or the dreams you brought with you. Or you could go to jail for insurance fraud after burning your buildings down. Or you could hang yourself from the rafters and make it all someone else’s problem.

Our own, brick farmhouse, its yellow paint repeatedly peeling in the summer humidity, was from the 1800s. Hanging in our bykeuken (uninsulated, room that acts as both a mudroom, often a laundry room, and the informal kitchen where the working wood stove is, where meats are hung and dried, and where the farmhands eat their lunch) was a damp-eaten, ornately wood-framed, black and white photo, maybe even a lithograph, come to think of it, of the stern looking couple who had founded our farm. They would stare down at the farmhands or family as we ate lunch.

My first real job was picking rocks in the neighbour's fields so their dairy cows wouldn't break their legs. In our own fields, my dad had me stoppering up groundhog holes with more rocks, as part of his plan to protect the cattle we grazed temporarily pre-slaughter from the same. My dad would then run water into the remaining open holes to try to drown all the groundhogs and their babies. I doubt it worked, since I doubt I found every exit. But you get the vibe here. Two alcoholic immigrant parents in a rural gothic dystopia.

Then, later, I married a horror writer.

AE: Your poems often end with endings cut off, which feels like a disruption of status quo poems where there's an epiphany or full circle ending. Can you talk more about ending poems with conjunctions and other unusual endings? Any pushback from editor?

AJD: The majority of pushback I’ve received from editors over the years has been when I try to wrap my poems up with an inauthentic, pretty bow, to round them out and make them neat and tidy and "finished". But that is not the nature of my content, or my writing style, or my mind. How can I end an exploration of the mess (glorious at times, but absolutely a mess) that we humans are, by coming to a single, poignant, epiphanic conclusion? And, what thought is truly complete? What is the end of a journey? At best, we are forever in some sort of motion, learning along the way, changing always. I have made my peace, and so seemingly have my favourite editors, with the fact that I am not, nor will I ever be “a sensitive man.” I don’t have it in me to “write poems about flowers.” But I’ll stay at the bar with you for the telling of stories that blend into both each other and the night, until

;)

AE: Joy is fleeting in the book, and when it appears, it is often associated with the speaker's memories of queer experiences, such as “Obsessive traits.” There is also joy in the play of language and the metaphors you use, the incantatory lists. What, if anything, brought you joy when you were writing these poems? How do you reconcile joy with the bleakness inherent in the collection? I loved the bleak imagery here. I felt it painted a reality that I understand, that you have not glossed over the direness of the 21st century. Do you think this is a pessimistic book? Where do you see hope if you do?

AJD: I see a lot of joy in these poems, but it is often the joy of expressing myself, and of standing up, for myself and others. Tears are important. Tears can help you process, can get you ready. But, to stand up and speak is to be filled with the joy that you can, that you are, that you know you have to. That you have been given the opportunity, and you are ready to give it to others. I am not joyful that we continue to shut people down. But I feel the enormous joy of gratitude that I can say “Look. We are continuing to shut people down. And it is time to listen to them instead.”

AE: The poems in response to Jon Crispin’s photographs of the abandoned suitcases at Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane fit really well in this collection. Can you talk about how you found out about Crispin’s series and why it resonated with you?

AJD: Jon is one of the few artists whose work moved me to reach out directly to them. I forget how I came across his online gallery, but I recall he had a fair number of suitcases and other baggage shot already, though he has done hundreds more since, I believe.

The Willard Asylum, which is a real place in upstate New York, eventually became a hospital before ultimately shutting down in the latter half of the 1900s. It’s a terrifying place, visually, geographically, and conceptually. The luggage Jon shoots was all found in a long-closed-off wing in the attic while developers were considering options for the property. From a shoe shiner’s work kit, to prosthetic limbs, embroidery tools, photos and love letters, pretty shoes and ribbons, the bags contained all the objects that were taken from new residents and never returned. Many of the patients, or inmates, lived out their lives, short or long, at Willard and were buried in its cemetery.

These were the days, from the turn of the to mid-20th century, when you dealt with someone who was problematic (your queer cousin, the wife you wanted to leave for another woman but couldn’t divorce for religious or other reasons, the son who came back from the war “changed,” your husband who wouldn’t get out of bed anymore, your sister who heard voices, your white neighbour who wanted to marry a Black woman, your girlfriend who tried to kill herself, and anyone else who was too much or too bothersome for you to handle) by sending them “away.” And Willard was far away, indeed.

For me, the place, and Jon’s striking photos of the last, lingering intimate details and priorities of these people, many of whom were intended to be forgotten, resonated deeply with me. Here was my worst case scenario, and also the very case against it, made manifest. To be diminished, discounted, discredited, deemed valueless and made into nothing but an absence, someone else’s regret. What Jon shows is in his photos is proof of life, however. Proof of value and individuality, of creativity and connection and everything that makes us human. That makes us worthwhile for the sheer fact that each of us exists. No matter our state or how we present to the world.

AE: Can we start a playlist for Crazy/Mad? I'd like to open with Lorde’s “Writer in the Dark.” What would you include?

AJD: Absolutely! I love books that come with playlists. I first saw it in queer romance (I chaired a Bi Book Awards Romance jury for a number of years), and am thrilled to see the idea spreading. Art always influences art. And music has been very important to me my whole life. I’ve put this one together. Honestly, I find Lorde a bit dodgy, politically/ethically, though I have included “Writer in the Dark” here, because it is, regardless, a good song: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/0k8jRw6K9DapwhnJnbwQZO?si=48de2af31c3b4489

Most are what you might expect, but “Het Kleine Café” (the little cafe) is a song my dad would listen to over and over again when I was growing up. It’s mournful, on the one hand, but is also a beautiful lovesong to a little, broken down pub, and the sense of community you get from going somewhere where you feel everyone is equal and content. Het Kleine Cafe is not fancy (“the only food you can get there is a hard-boiled egg”), but, as the song says, “It is a very good Cafe.”

Amanda Earl (she/her) is a queer writer, visual poet, editor, and publisher who lives on Algonquin Anishinaabeg traditional territory, colonially known as Ottawa, Ontario. Earl is managing editor of Bywords.ca, and editor of Judith: Women Making Visual Poetry (Timglaset Editions, Sweden, 2021). Her books include Beast Body Epic (AngelHousePress, 2023), Genesis, (Timglaset Editions, 2023), Trouble (Hem Press, 2022), and Kiki (Chaudiere Books, 2014; Invisible Publishing, 2019); A World of Yes (Devil House, 2014) and Coming Together Presents Amanda Earl (Coming Together, 2014).

Her latest chapbook is The Seasons, an excerpt from Welcome to Upper Zygonia (Full House Literary, 2024). More information is available at AmandaEarl.com and https://linktr.ee/amandaearl. You can also subscribe to her newsletter, Amanda Thru the Looking Glass for sporadic updates on publishing activities, chronic health issues and joy in difficult times.