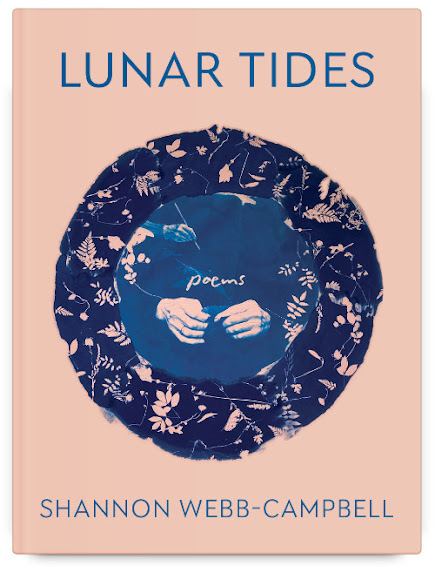

Lunar Tides, Shannon Webb-Campbell

Book*hug Press, 2022

Show me someone who is a poet who hasn’t written a poem or two about the moon. We poets are transfixed by it, and it perhaps presents symbolically as being much stronger (as a force) for those of us who are women. After all, we are governed by its tides on a monthly basis, aware of its push and pull on us through cycles and over time. Too, this moon that we watch move through its cycles each month—up high in the sky above us—is one that has been there since the beginning of time. The moon is a fertile symbol, in so many ways, for poets, and Shannon Webb-Campbell delves into this symbolism in her newest collection, Lunar Tides.

She does this is a unique way, not falling prey to the cliché that sometimes arrives when we write of the moon’s significance, tying its phases to the loss of her mother. Her moon is one that has been present in the sky for eons, has watched the passage of time and of human lives coming and going on the planet, but also one that marks the grief of a mother’s departure. It’s a powerful moon, the one Webb-Campbell conjures in her work.

Grief might be one of the last stigmas to fall in the western world. We have a society that tends to rush us, to want to rush through it all so that it’s over, as if that will make our mortality less certain. The collection begins with the haunting question “What phase was the moon when she left?/ How high or low were the tides?” If we can fix a time of departure, the poem suggests, perhaps we will better understand how to deal with the great loss that comes with a physical death.

In “Postscripts & Moon Tea,” the poet reflects on the process of “sorting through boxes of letters and photographs/old pockets of intimacy and memories,” as she finds her “grandmother’s handwriting/on the back of a bank statement.” There is an ache upon this discovery, a frisson of grief that ripples with memory. In “Grief: Q&A 1,” there is a dialogue between interviewer and speaker. The interviewer asks, “How do you cope?” to which the speaker answers, “I can’t find her, keep asking strangers—have you seen my mother?” Whether these are two separate people (or voices), or whether this is just a sample of the internal dialogue that one engages in after a deep loss, really doesn’t matter. The essence of that hollow ache is clearly conveyed.

In “Grief: Q&A II,” there is mention made of the five stages of grief. The conversation continues: “Q: Do you think there are more stages?//A: Yes.//Q. Like what?//A: Ask the displaced moon.” Grief displaces the moon, something that has been constant for a person’s lifetime, but which seem at sea, or upended in surreal fashion, after a daughter loses a mother. There is no anchor left when a mother goes away, and the daughter is left stranded.

In “Moonstruck,” Webb writes: “I’m like the wind/made of grandmothers and moonstone,” alluding to the strength of matrilineal inheritances through culture and family. When someone goes, though, sometimes it seems that the only thing that still connects one to the other—alongside memories—is the moon. In the impermanence of the moon’s phases (but in the permanence of its having been part of the human landscape for millennia), the poet seems to suggest that we might be able to find some modicum of comfort in our grieving.

There are beautiful love poems in Lunar Tides, too, as Webb reminds her readers that, even though we suffer great loss and grief, love remains as a hopeful note or addendum. In “Lemon Came in the Night,” and “Not Knowing the Book of Myths,” she writes of the aliveness that comes with being in our human bodies, full of desire and physicality. In “Slow Dancing in a Bachelor Apartment to Joni Mitchell,” two lovers dance, “pulling each other close/never wanting to be blue again.” Later, in “I’ve Been Taken By Colette,” on a “maiden voyage into Conception Bay,” the lovers dangled their toes over the surface of the ocean and “blew kisses to sea beings.”

The landscape of Newfoundland weaves itself in the final portion of the book. In “Final View of Bell Island,” the poet writes of how her mother “never wanted to be buried,” and how she “scattered her ashes off flat rock/tossed orange roses into grey ocean/down the Irish shore.” Later in the same poem, Webb writes: “Mom asked me to put her ashes/under her saltbox/but I was told/no one wants your mother’s/remains under their house.” As a reader, I chuckled. I am also a daughter who has lost a mother and recall the conversations about what to do she wanted me to do with her remains. These are the things mothers and daughters converse about near the ends of mothers’ lives, it seems.

What rises above everything else in this collection of poems is the deep love that is woven into all of the poems. How does a daughter remember and mark her mother’s life? Webb does this beautifully in Lunar Tides, not flinching or avoiding death or loss. In many ways, the moon in Webb’s collection reminds me of the sea in Agnes Walsh’s Oderin. If you’ve read both, you’ll know what I mean. If you haven’t read both, I’d highly recommend them.

Kim Fahner lives and writes in Sudbury, Ontario. Her latest book of poems is Emptying the Ocean (Frontenac House, 2022). She is the Ontario Representative for The Writers' Union of Canada (2020-24), a member of the League of Canadian Poets, and a supporting member of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. Kim's first novel, The Donoghue Girl, will be published by Latitude 46 Publishing in Spring 2024. She may be reached via her author website at www.kimfahner.com