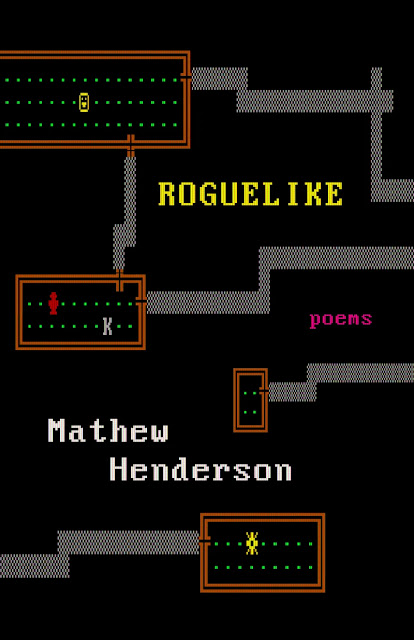

Roguelike, Mathew Henderson

Anansi, 2020.

Roguelike is a collection that draws upon the conventions and structure of online gaming culture, but the poems are richly and diversely textured—with references not only to game mythology and fantasy, but also to the ways in which families and addiction are often intertwined. You needn’t worry that you won’t understand Henderson’s work if you aren’t a ‘gamer.’ You will. His is a poetry that is full of sharply turned lines that will sit in your mind for a while after you’ve read the book. Henderson finds fragments of story, weaving them into a net of meaning, and lifting up the process of how we can make meaning of our lives through writing.

In “After the Arctic, April, 1993,” he writes that “an ocean poured into glasses remains a single thing.” Something large, voluminous, like human emotion—or the ocean—can become something that is also distilled, made even more potent. In “Leaving Woolfe’s Corner,” there is the sense of being trapped within a house. Henderson writes, so adeptly here: “You knew already how a house could pile/upon your chest, could pin you sure as a railway spike.” Not every house is a safe place, and not every house is a home. Here are massive things artfully conveyed in tiny, meticulous details.

In “Liminal,” the poet writes about how it feels like to leave a workplace at the end of a long day, to “find my way/free of the usual currents, get caught in another eddy and wind up/outside of it all.” He speaks to how we, as humans, move between our various worlds and memories—and of how we sometimes find ourselves more free in those ‘in-between’ places that can’t always be defined. We live transient and temporary lives, even though we try to fasten them down with meaning and permanency. In “XVII” of the poetic sequence, “Crono,” Henderson writes of “the thinnest places I’ve been, the only places I’ve/been where I can imagine finding a seam, I think, or an edge.” He looks for the conjunctions in a life. “There are so many endings for us, Mary,/but it always starts the same. The sudden light, the sleepy gulls.” And so, Roguelike asks its readers to step inside, to journey within the collection, and to search out their own meanings.

My favourite section of the collection is the final one, “End/Game.” For me, it calls to mind Samuel Beckett’s play of the same name, but I am aware that it has an alternate meaning for gamers. For them, ‘endgame’ means that they are transitioning to a higher level of skill, that they have learned as much as they can from the level they have just played through—whether alone or in collaboration with other players. It’s a fine metaphor for how we live our lives as humans, and how we learn and grow, encountering challenges and celebrating our small triumphs when they arrive.

In “Streetcar Heatmap,” the poet writes of how he has traveled through a neighbourhood “where I’d spent/several years in love, and I began to see myself on the street.” It’s reminiscent of how we are haunted by memories, and how—the older we get—we gather more and more images and memories of the lives we’ve lived within this one. In “Randomizer,” the first line pulls you in: “In this one, I go to school in Alberta and you work at the hospital as an ultrasound tech.” You want to read on. It feels like a moment in time that is private, but still not off limits, at the very same time. The result is a bit of poetic seduction for a reader. “I know/the artist must have believed what I believed, in the stars beneath/our skin, the secret, the glitch, and they learned what I am learning,/that there is no secret to life.” You want to be present, and you want to be invited into the memory and the meaning making.

What drew me into Mathew Henderson’s Roguelike was the sense of a poet trying to create a narrative, a writer trying to gather fragments of memory and family history, of a person weaving stories of love and loss, and of structuring a narrative frame that would offer a sense of being grounded. If you’re grounded, I kept thinking as I read, then maybe it will be less terrifying as you move forward in life. If you can find your feet under you, if you can know that your past influences the present but doesn’t automatically define your future, then there is a sense of freedom and creativity in that notion. Roguelike is thought provoking and deserves more than a few quiet readings—over a period of time—and with close attention to Henderson’s skillful work as a poet.

Kim Fahner lives and writes in Sudbury, Ontario. She was poet laureate in Sudbury from 2016-18, and was the first woman appointed to the role. Kim's latest book of poems is These Wings (Pedlar Press, 2019). She's a member of the League of Canadian Poets, the Ontario representative of The Writers' Union of Canada (2020-22), and a supporting member of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. Kim blogs fairly regularly at kimfahner.wordpress.com and can be reached via her author website at www.kimfahner.com