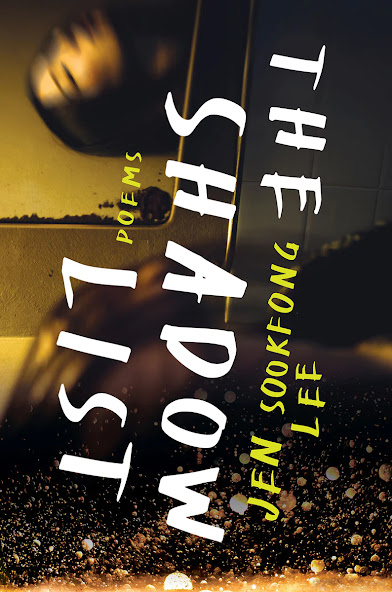

The Shadow List, Jen Sookfong Lee

Buckrider

Books, 2021

The poem “Anatomy," from the collection The Shadow List, feels like an exhilarating sprint away from certain death, past scenes that might draw you in and hold you in the thick glue of memory. None of that happens in the poem, mind you – the poem deals with how a woman relates to her bruised body. Jen Sookfong Lee ends the reader's dash through “Anatomy” with a still image, a surprising calm moment of dream-like lack of breathlessness, and punctuates the biting calmness of this ending with a simple line: “You may as well have no skin at all.” (72)

That line, its clear indication that there is skin, its implicit portrayal of brokenness and violence, its blurring of you as speaker speaking to themself, of you as unnamed addressee of the speaker, of speaker and author, of you as reader; it casual harshness, its sadness – that line has come to represent Lee’s collection The Shadow List to me, as I move through it out of order now.

I came to this collection late – even Wolsak and Wynn thought so. I had listened to Lee talk about writing it on Can’t Lit, the fantastic podcast she co-hosts with Dina Del Bucchia, and then talk about the collection on a very special episode of the podcast. I kept meaning to get the collection, request it, read it, and even when I finally received it I let it sit and even when I picked it up I was not ready for it. I had read some of Lee’s novels – I couldn’t help but see her in the lines “You are used to writing novels, / to placing a human in the middle / of a slowly unwinding nighttime dilemma, / darkness hiding her indecisive, rock-heavy feet” (33) – so I was expecting a darkness. But I hadn’t anticipated the confusion in relation between self and self and other that the collection brought about. By confusion, I mean that the poem titled “Third Person Intimate,” where the above lines appear, is about a novelist’s protagonist, written in the second person, about a writer that feels like Lee but, the podcast episode tells me clearly (that is, if I recall it correctly), is another character, one who feels so completely alive and real. Are there different speakers in these poems then, each a different character? Does Lee herself speak? How do they all feel so alive, how do they carry so much sadness and hurt?

These questions are easily reversed into answers: the poems may be an exploration of sadness and hurt, drawing on lived experiences but transformed into other people’s. But I remain awed by the craft, stuck with the question how does she do it? How does Lee give me the sense that there are many real people in all these poems, to the point where I have to force myself to not read her into each character, knowing that would be entirely wrong and missing the point? While the speakers and the addressees feel entirely real, the second person writing annuls any sense of confession, and the fragmentary insight leave out any omniscience. We’re left to observe, and wait.

Looking into moments of anguish in these character-speakers' lives, we’re left with a sense of darkness. While there’s much sadness, loneliness, and aftermaths of violence in the text, these poems respond in kind, bringing into play alternative experiences, active and willful ones, of sadness and loneliness; a violence, a rage, a fury that might end violence by bringing another reality into being: "This violence, this volume / is how you will try to change what seems like fate." (16)

Further, on this darkness: I may never have read a book that takes place so completely at night. Everything is bathed in a worrisome yellow, reminded me of streetlights from before LED bulbs, or bedside lamps before cell phones. The film noir book cover certainly does its part. Silence, loneliness again, the many directions shadows can occupy at once. And through all this fear, the attempt to see: to really focus on what isn't coming to light, to stare so hard the light might direct itself toward it:

"The broken lamp beside the garage buzzing, a raccoon

walking upside

down, claws tapping and tapping

on the gutter it

clings to. You squint, the continued

watch in the

night. The black hurts your eyes.

Do you know what

you're watching for?" (41)

Lee places the tumult inside, even as it is projected outside: "The wind is in your mouth now anyway, a cyclone." (42) The shadow list is one that accompanies the expected, imposed list of wishes – a list of desires, not forbidden or hidden, but rather desires that are as ordinary as the shinier, movie-inflected ones we expect to find in other people; desires, however, that are simply not supposed to be spoken even if they are already shared by others.

This shadow list is also a matter of diction: among children, dogs, bunnies, and raccoons (more than one and more than once!), Lee places words that slice: sliver, cracking, pyrite, scythe, chrysanthemums; slip/scream placed near each other; "fractures thin as threads"; "secrets, indecent and jagged"; "the skinniest shadows"; "the knife edges of paper"; "the edges of your longwear lipstick like scalpels" – and as with "edge," a careful repetition of words here and there in the collection, visible threads that hold the assemblage together.

One poem spells out a task, perhaps inherited as fate: "The lights are what people want to remember. [...] Only you will remember." (43) Only you, however you, as in a fate or mission of sorts; Only you, you alone, as in the loneliness and withdrawal within oneself that creeps through the collection. I could keep quoting from this immense poem, “Tornado,” that stands in the middle, at the top, of this collection. Others reach further into various pasts, some slow down to describe the bodies of men, the softness and vulnerability around their hardness. Some, only a few, indicate the possibility of futures by lingering on the obliviousness of children to their present.

The future isn't within the scope of this book, which is solidly set in the present and what we make of the past. The Shadow List is very much what it has to be: its length gives us a sense of plenty, but no bounty, only satisfaction. There’s pain, but no exposure, no room to stand as a voyeur. And the more I read these poems, the more riveting they become – what a feat it is to make non-narrative poems so riveting, so revealing of what we keep to ourselves.

Jérôme Melançon writes and teaches and writes and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His most recent chapbook is with above/ground press, Tomorrow’s Going to Be Bright (2022, after 2020’s Coup), and his most recent poetry collection is En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He has also published two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016), as well as one book of philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018). He has edited books and journal issues, and keeps publishing academic articles that have nothing to do with any of this. He’s on Twitter mostly, and sometimes on Instagram, both at @lethejerome.