HENRY MILLER (Three Visits)

It isn’t far from the Pacific Coast Highway to LA’s Brentwood, the upscale neighborhood where Henry Miller moved in the 60s, after decades living in a cabin in Big Sur. I have the address, and I find the street. My father, Lafe Young, used to supply Henry with books when he needed them. They’d met in 1940, and stayed in touch as friends. After the Tropic Of Cancer got busted for obscenity, and after the sensational trial in the fifties, fate had made Henry a rich man in his early seventies.

A handsome two-story house on a curved street, 444 Ocampo Drive even has a swimming pool. I am twenty years old. I knock on the door. In a month I will take a student ship to England, then spend four months in France as a student followed by five months hitching from Madrid to Istanbul, from Zagreb to Copenhagen, from Florence to Brindisi, from Geneva in a snowstorm to Paris, among other improvisatory escapades, including Tangiers.

It is suppertime and soon Henry puts a gin & tonic in front of me, followed by a pork-chop. He urges me to read Jean Giono, Blaise Cendrars, and Camus (but not Sartre). He isn’t too busy to praise his peers, or ask a question. Brushes and colors and paper for watercolors cover the desk in his office, and on one bare wall he has scribbled all manner of quotes from his reading, in pencil and marker and crayon. Boho chic! We sip, we eat, we talk, I listen. After supper, as he smokes a cigarette, I thank him for dinner and the visit, and depart.

Two years later, it’s the spring of 1966, and there is an important show of works by Henri Matisse at UCLA. I’m a student in Santa Barbara where Hugh Kenner smokes two Salem cigarettes per lecture on Jonathan Swift or Beckett or Pound. And my folks are in San Diego. We agree to meet at the gallery on the UCLA campus at noon. It is the first chance for any of us to see “The Red Studio,” among other works. The show’s a knock out and we’re all reeling. Then we get in our cars and I lead them to 444 Ocampo Drive. My father raps his knuckles on the door. I don’t think the visit has been planned. Henry opens the door wide and steps out, an unfiltered Chesterfield cigarette wet in his lips. He looks at my father and mother, stands back a step, notices me slightly behind, then with a big smile on his face, gives my old man a big kiss on the forehead. We are ushered inside.

He tells my parents that he’s been married to a Japanese woman half his age, but that she recently moved out. Henry shows us around. Office, kitchen, living room. We don’t go upstairs. Now there is a ping pong table out by the pool. Don’t think my father and Henry have seen each other in twenty years. Much talk, easy camaraderie. Henry’s Brooklyn roots still evident in his measured sound, a gutteral vocalese punctuates things he says.

Then a year or two go by, and my father says, “Why not stop at Henry’s on your way through LA and ask him to sign the watercolor we’ve had in the house for years?” We grew up with this watercolor, an imaginary laurel-crowned self-portrait, with a gnarly blue homunculus animating one side of the work. Henry hasn’t signed the work. Probably a gift given to my folks in the forties.

It’s noon. I knock on 444. A tall black man wearing a white jersey answers the door. I state the reason I’ve come, and the man says, “Wait a minute.” He takes the watercolor to Henry. Pretty soon I hear Henry say, “Ah, I almost remember doing this one.” Henry is in bed, suffering from a late-life bout of shingles, seeing no one. He’s a few rooms away. I can hear, but not see him. A few minutes later he has signed the work in the lower right corner. The man hands it to me. I raise my voice a few notches and project, “Thank you, Henry. Feel better!”

And as the man ushers me out, I thank him as well, for all he’s doing.

MIKE BLOOMFIELD & JANIS JOPLIN

The only chance I had to hear Mike Bloomfield live was at the Earl Warren Showgrounds in Santa Barbara in 1967 when he and ex-Wilson Pickett drummer Buddy Miles lead the band called Electric Flag at a three-band concert featuring Sweetwater and San Francisco’s own Big Brother & the Holding Company. Stepping out onto the stage, Buddy sat behind the tubs and Bloomfield, still in an overcoat, grabbed the mike and said, “We’re gonna start this set with “UPTIGHT,” cuz I am!”

Seconds later, Buddy Miles’ downbeat was a blast of drum-sticks on taut skin, then Bloomfield, amped to the max, started sawing on his ax and “Uptight” was in the air, as antidote or necessary evil or nervous launchpad or ice-breaker complete, who knows. The Flag’s show had begun.

It had only been a short while since Bloomfield had gained notice with Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and, more important for this account, Bob Dylan’s mid-sixties transition from folk to rock.

Decades go by and somehow I’ll hear a Dylan song from that short-lived period

in 1965 when Bloomfield was his lead guitarist and I feel it all over again, the brash confidence and raw emotion of the Bloomfield guitar lifting the Dylan book into the rock and roll music he loved as a teen. Who can forget the playing on “Maggie’s Farm” at the Newport Folk Festival that year? You Tube hasn’t. Maybe you gotta be my age to remember it? To care about it?

For a short spell—how many months?—Bloomfield and Dylan were close, their recorded versions elevating the songs to new heights, and their live concerts insane. Later, as careers moved on, I followed Bloomfield at a considerable remove. There were bands and gigs and travels and disappointments about which I know very little. But a few years later, in Rolling Stone, I read that Bloomfield had died in the Bay Area of a drug overdose.

“Uptight” cleared the air that night, then the Flag’s set-list took us to blues joints with broken hearts and other soul theme-parks. There was no dearth of big drum beats from Buddy, and no end of scorching solos from Bloomfield. If people were dancing in back I didn’t see them. We were in chairs, seated somewhere in the front five rows, digesting the brownie we’d eaten during Sweetwater’s set, following every wind-blown ripple in the waving flag.

And up next? Embarrassment of riches? Janis Joplin and Big Brother. With that great name, the Holding Company was huge already. Janis was the reason. The audience was clearly up for it, but song after song, nothing happened, the evening didn’t catch fire. Either the band was dragging, and she couldn’t feel it, or she was bored with yet another repeat performance of the material.

But then, somehow, how? a few songs later, something clicked. Janis wanted more and the musicians dug in and found it. Now she responded with passionate versions of her big hits. She’d shimmy and shake with the feeling as she pushed it and the song built. I’d never seen anyone inhabit a song so desperately, so driven to be the quivering sensitive edge of it. She was sweating, she was moving, she was a heart in tatters. Music was a vehicle, not of transference (to what?) but of ecstasy. Feeling oozed from the center of her body, radiating outward like after-shocks from an earthquake. Finally, she was free. Finally, Janis, the band, and the audience were one.

DUNCAN HANNAH

It was in Soho, at

Barry Blinderman’s gallery, Semaphore, that I first saw Duncan's work. Don’t remember who urged me up those steps to

a second floor space on West Broadway near Prince, but it must have been the

mid-80s.

Among other

paintings, Semaphore was showing Duncan’s portrait of the great tenor

saxophonist, Lester Young, upright in a small room. Was Lester sporting his porkpie hat? I haven’t seen the picture since. “Prez” had died in 1959, a jazz legend. I asked the price of the picture—it seemed

fair—but I couldn’t afford it.

Then somehow, how?

In 1989 Duncan sent me a copy of Duncan Hannah 85, which he described as

“an old chestnut.” I looked closely at every picture in this catalog. It gathered his recent paintings and

drawings, and provided a smart essay by Carter Ratcliffe.

From then on I saw

his shows as they happened in New York.

Once I opened a gallery in Great Barrington, MA in 1992, I would include

Duncan in many a group show over the next twenty-seven years.

In 1996, Duncan

made sixteen drawings for Arts & Letters, the name of his

collaborative book with Michael Friedman’s prose poems, published by The

Figures. That chapbook remains a great

juxtaposition of like-minded sensibilities.

Terrific to look at, charming to read, and right at the level of

feeling. I showed all sixteen drawings

at the gallery in the fall of 1996 where they were bought by the collector A.

G. Rosen.

Always good to

visit Duncan on W. 71st. Just

inside the entry-way there was usually a stack of completed works leaning

against the wall, as well as a work in progress on the easel. One of a number of cats over the years would

be there, sometimes as a drawing on an easel, most often asleep on a sofa. When my cat Eartha had six kittens in 2013,

Duncan and Megan took the dashing young eight week old Tarzan off my hands, to

be paired with their Jane.

Duncan worked and

read every day. He always said yes when

I invited him to be in a show. He chose his subjects carefully. His passionate interest in certain periods of

the recent past set him apart. Sober and

thoughtful, his paintings told sympathetic stories that ranged from childhood

nostalgia to youthful beauty to the precarity of a Hopperesque loneliness. Tradition mattered, just as flesh did; old

movie stars—or Italian models--back when they were young, were made eternally

so, under his brush.

It was a pleasure

to see the variety of works in his collection, as well—some English, most

American—together with art books on table tops and shelves. Studious but not pedantic, his memory was

legendary. An impeccable dresser, Duncan’s pleasure in draping himself

tastefully, as if imported from an earlier time, was nonetheless invariably

compelling. None of us yet knew that his diaristic memoir, Twentieth Century

Boy, would show up to great acclaim in 2018, making the phrase “riotous

youth” so attractive.

In a handwritten

note dated Oct. 17th, 1989, after I’d sent him a letter defending

his work, he wrote, “Sometimes it feels just like the pool is full of sharks,

their irony meters running, and I’m found wanting. I certainly never set out to

be an anachronism. I paint for a

fictitious audience in my head and hope they’ll understand. Hope they’ll exist! You do. Thanks.”

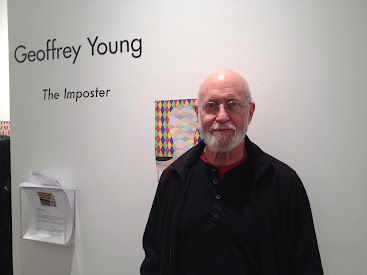

Geoffrey Young was born in Los Angeles in 1944, and grew up in San Diego. He has lived in Great Barrington, MA, for the last 40 years. His small press, The Figures (1975-2005), published more than 135 books of poetry, art writing, and fiction. Recent books include Monk’s Mood (2023), DATES (2022), and Pivot (2021). After twenty-seven years, he closed his contemporary art gallery in 2018.