South China Sea, A Poet's Autobiography, Ken Norris

Guernica Editions,

2021

If

Ken Norris's South China Sea (2021)

reminds me of any book, it is Leonard Cohen's Book of Longing (2006); both are books of poetry written when their

authors were older, accomplished, and respected poets. While Cohen's book reflects

on various aspects of his past from the perspective of his present life, it is not

deliberately autobiographical; it is a collection of poems, drawings, and song

lyrics. Norris's South China Sea is

his autobiography; in one poem he wonders if Wordsworth's idea of

"abundant recompense" applies to his life experiences; however, "the

still, sad music of humanity" most accurately describes Norris's poems.

All of Ken Norris's poems in South China Sea are written in direct

and unadorned English; this is an achievement, it is more difficult than most

people realize. Sometimes these poems are nostalgic, sometimes these poems are self-deprecating,

sometimes they are self-aware and insightful; and sometimes Norris presents a

dark vision of life. All of Norris's poems in this book are authentic expressions

of psyche which is part of the beauty and accomplishment of the book; it is

this aspect of South China Sea that I

will concentrate on.

South

China Sea is autobiographical in the way that C.G. Jung's Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1962) is autobiographical,

both are "partially autobiographical". Norris's poems recount events of his life and some of these

events may seem minor but all assume significance when put in a poem. This is

not a traditional autobiography, it is not a travel diary, it is not anecdotes

of well-known poets Norris has met or known; there is some mention of a few significant

family members, and friends, and acquaintances that were a part of his life; but

the depth of the book is found in the layers of inner experiences that reveal

the man who has lived this journey. Just as "Tintern Abbey" is

Wordsworth's autobiography, at least in a spiritual sense, this is Norris's impressionistic

and subjective autobiography, an autobiography of the soul and the perceptions

and experiences of the soul; they are poems about his journey in life. Norris

writes,

I hear the

roosters

beyond the city

limits

and know that

dawn has arrived.

A faint light

peeking through the curtains.

Sleepless, awake

since five,

I can't make any

sense of my life.

The train wreck

of dreams behind me. (92)

All poets want to communicate. Writing

poems is to create a bond with the reader, it may even seem to end the poet's exile

or feelings of alienation. What keeps poets writing is the need, sometimes obsessive

and always relentless, to get what they have to say perfectly and exactly expressed.

Most poets have only a few things to say, only a few themes, but they keep returning

to these few things, in book after book, over a lifetime; this is what Ken

Norris has done. And if this succeeds then it should communicate to the reader,

it might achieve communion between the poet and the reader and, coincidentally,

it creates a communion, an understanding, for the poet and his unresolved inner

self.

When anything is done in apparent excess there must be something more going on than what appears on the surface. William Blake famously wrote, "The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom." Norris's travels to different, often exotic, countries are not ten day all-included vacation packages, they are more adventurous and long term than that; Norris is no average tourist, it is also inner journey that he is on; he writes,

Sometimes I went:

off to Asia, down to the Keyes

and Caribbean, over to Europe

for the pleasure of a song.

Anything to get out of

dumb, anesthetized America

where the ether had taken hold,

and everyone was a patient without insurance.

(59)

There is an ironic aspect to this, travel can be both an escape from the self and a discovery of the self; in either event, the self one wanted to escape is usually waiting at the airport to welcome you home. Exile is imposed on some poets, for instance Dante's exile, but there is also exile from one's inner self, one's substantial self. Think of the meaning and context of the artist's exile as it is discussed in Colin Wilson's The Outsider (1956); the title gives something of Wilson's idea of the artists' position in relation to society; he or she may be in society but not of society. Norris writes, "I was always the wanderer/ the exile, sad Ishmael." (37) Robin Skelton writes, "We are all exiles seeking our unknown origins." Robin Blaser described Louis Dudek as a "walking loneliness", someone who was isolated in his own consciousness, someone not at ease with the common discourse of most people. For health reasons D.H. Lawrence escaped Britain's inclement weather but he also wanted to escape "the bitch goddess success" and the British class system, and much of his life was spent in travelling, in exile, moving from place to place;

Norris writes, "I was an exile/ from America, desperately trying/ to find a home." (33)

Romantic relationships recounted in Norris's other books need to be mentioned, they are a consistent presence in this book. For some, romance can be an escape from one's self, from feeling alienated or in exile. Some of the time these relationships may be genuine communion with another person and sometimes they are an obsessive repetition of choosing the wrong person.

Now, let's consider a Dantesque

experience of seeing an expression of the feminine, a Muse figure, in a young

woman who happened to cross Norris's path, and how this transformed the young

Norris into a poet; although he couldn't have known it at the time, it was a life

changing experience, it was when he crossed the threshold into adulthood; Norris

writes,

Fifteen years

old.

Reading James

Bond novels

and listening to Revolver.

I saw her

walking down the

street

barefoot

and that was it

for me.

Introduction to

the muse.

I started writing

love poems

in a blue-lined

composition

notebook.

The poems were

awful,

and being

love-struck

and tongue-tied

like that

was even

worse.

(168)

In this Norris has his own teenage

experience of the positive feminine; it is also his introduction to writing poetry.

After this, everything else follows: travel, exile, romantic relationships, poet

friends, and writing poetry. Like all good travellers, Norris has reduced his

life to essentials; the three pillars of Norris's autobiography might be travel, the

feminine, and writing poetry. Discovering the feminine is both his

awakening and his downfall; it is the leaving behind of childhood consciousness

and the birth of being a separate person with desires and needs that may or may

not be satisfied; he writes,

There's no doubt

that I ran

that I was

constantly running away.

To Canada, to

exotic islands

where the air breathed

spice,

to foreign cities

that contained

a thousand

unimagined mysteries.

Yes, I travelled,

while everyone

else

stayed home.

(60)

One of Ken Norris's biggest

supporters was Louis Dudek. Dudek always rejected autobiography; he felt that whatever

he was willing to say about his life was revealed in his poems, as Susan

Stromberg-Stein has written about in Louis

Dudek: A Biographical Introduction (1983). Dudek said

that fame is just a way for strangers to pester you, but fame is seductive and

our society is built on a foundation of desiring fame and fortune. As a social

conservative at a time when so many were "doing their own thing", or

what Matthew Arnold termed "doing as one likes", Dudek was critical

and felt apart from and critical of contemporary society, but compounding this

were the poems he was writing, poems that most critics didn't like; I refer to Continuation (1981, 1997). Exile and old

age can be lonely; in Dudek's old age he would ask if you were free to have

coffee with him, usually at the Alexis Nihon Plaza, within walking distance of his

home. I regret I ignored these invitations. What was Dudek's religion? Agreeing

with Matthew Arnold, Dudek said his religion is poetry; Arnold wrote, in "The

Study of Poetry", that "what passes with us for religion and philosophy

will be replaced by poetry." Dudek knew that a poet's redemption is in poetry, redemption

is in communion and poetry is the source of a poet's communion, but it is also the

integrating source of the poet's existence. Norris writes,

I live like a shadow.

I keep my essence

concealed.

No one knows the complete

me.

I have friends for all occasions,

but none of them can

calculate the complex angles.

In truth, I'm addicted to

anonymity.

I write my books from the

depths of my secret life

and hold them back till the

self that wrote them

has evaporated and changed

into someone else.

I'm

never happier than when I'm faceless and nameless

in an obscure hotel in a

country

no one's ever heard of,

in a place where no one I

know has ever been.

(90)

And then, a few pages later, Norris

writes,

Thoughts of Louis, his

Atlantis,

and where exactly do I find

Taishan?

I'll find out, consult a

map,

and go there.

If it still exists.

(93)

I am not a traveller, I prefer the comforts of home over

airports, foreign cities, and the loss of belief in my own existence I suffer after

a day of site-seeing; I can take only so much wandering around as a tourist

before I want to return home. This is some kind of purgatory Norris has visited

on us, "As if life were/ an hour in a bus station.// Waiting for the bus

to depart/ to that better destination." (129) But it's not an hour, it's a

lifetime of "waiting for Godot", and it is not mere site-seeing, it

is being driven by a need to travel. The journey is universal; it is

Gilgamesh's journey, it is Odysseus's journey. It is also an American archetype;

it is Whitman's open road, Kerouac's on the road, and others. But it isn't Henry

David Thoreau's way, he was no traveller and never went far from Concord; Thoreau

observed, "I have travelled a good deal in Concord; and everywhere, in shops,

and offices, and fields, the inhabitants have appeared to me to be doing

penance in a thousand remarkable ways." Thoreau's observation that

Americans, and others, live lives of "quiet desperation" still

describes contemporary life over 170 years since Walden was written. We are all seekers for truth, for meaning in

life, and for Thoreau staying in the same place was an opportunity for introspection

and simplifying one's life, but Norris finds the inner life in travel.

Where can we find communion with something

that ends our sense of isolation? Is it found in Atlantis, that mythical place

in Dudek's poetry? Or is redemption in Taishan which Norris mentions? When Norris mentions

Taishan he reminds us of Ezra Pound's Pisan Cantos; after World War II Pound

was incarcerated in Pisa, for treason, and associated a hill he could see on

the Pisan landscape with Mt. Taishan, a mountain which has spiritual importance

in China. This association gave Pound hope at the time of his deepest despair;

it also reminded him of the feminine and redemption by the feminine. Norris's allusion

to Pound's Pisan Cantos, one that would have been familiar to Louis Dudek who

was a friend of Ezra Pound, deepens our understanding of South China Sea and helps tie together three aspects of Norris's

writing: travel, the feminine, and writing poetry. Most of us will never be

travellers to the extent that Ken Norris has travelled but we are all on this

journey to find meaning and purpose in life. This is the inner journey, in

search of individuation, and it is the journey described in Ken Norris's South China Sea.

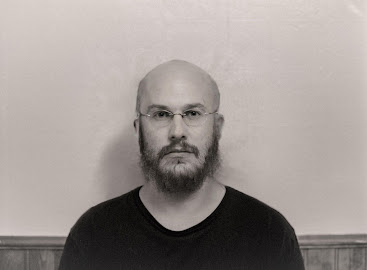

Montreal

born poet Stephen Morrissey is the author of twelve books, including

poetry and literary criticism. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree,

Honours in English with Distinction, from Sir George Williams University in

1973. In 1976 he graduated with a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from

McGill University. In the 1970s Morrissey was associated with the Vehicule

Poets. The Stephen Morrissey Fonds, 1963 - 2014, are housed at Rare Books and

Special Collections of the McLennan Library at McGill University. Stephen

Morrissey married poet Carolyn Zonailo in 1995. Visit the poet at

www.stephenmorrissey.ca