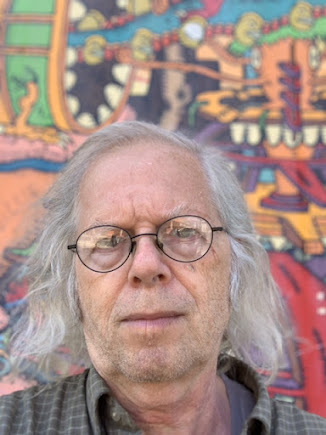

A Busy 2021: Poet Ken Norris Delivers a Major Collection and Two Significant Chapbooks

An active poet who has published over 30 collections since 1973, Ken Norris continues to expand his poetic explorations with three new works released in 2021, including a major collection he calls an autobiography. In this conversation with Jim Mele, a long-time friend and collaborator on the Canadian/US literary magazine CrossCountry, Norris talks about memory, aging, travel, poets wrestling with death, and plans for his next projects.

Jim Mele: You are by any standard a pretty prolific poet.

How many books at this point have you published?

Ken Norris: I don't know. More than 30 books of poetry.

JM: Even by those standards, 2021 has been a real banner year for you. You had three collections come out-- the two chapbooks Hawaiian Sunrise and The Stray Dog Café, and a major collection with South China Sea. What was going on? Is that just the way they made it to print or was it a sudden burst of energy?

KN: Maybe a little bit of both. Unlike the chapbooks, I actually finished writing South China Sea 10 years ago. I was sort of in the later days of teaching, so that kind of slowed that book up. And then the publisher pushed it back some. So usually there's a three to five year lag these days, but it became a decade. I signed the contract on that book in 2017, but it didn't get published until 2021. That was just the publisher's scheduling.

JM: Let's talk about that one first. It's a major collection in your publishing history. How many years does that work span?

KN: I started writing it when I was 57, and I stopped writing it when I was 60, so it's three or four years.

JM: You call this one an autobiography. Almost all your poetry is intensely personal. So why is this one labeled an autobiography?

KN: In a way, it's a bit of a marketing ploy. At a certain point I was thinking it's just the latest collection. But there are things about it that makes this book different. I started writing it when I was 57. My grandmother had early onset dementia, which started happening for her when she was 56, 57, so I got a little twitchy when I was 57 and kind of thought I don't know how long my memory is going to hold up. Maybe I should start doing all of my remembering now rather than waiting till I'm 70, when maybe I won't have any memory. So that's really what prompted the book. And I thought of it very much as a memory book. I was going to go back and try to retrieve things that I had never written about before.

And the other thing was I was having conversations with both Endré [Farkas] and Tom [Konyves] about what my life was like before they ever met me, because they met me when I was 24 years old. But, you know, I met you when I was 17. So there was college life and there was rock band life and stuff like that. And I never really addressed any of that. So, in a way, I started writing about that stuff to explain to them who I was before they ever met me.

JM: I wouldn't say it's all retrospective, but everything's mostly in the past tense. Do you see it as a summation of your life, or is it more an attempt to reconcile with your life's contradictions?

KN: Yeah. Given the 10-year lag, right. I finished writing the book when I was 60, but it didn't get published till I was 70. When I was proofreading it, I wanted to rewrite just about all of it, because ten years have gone by and I just wouldn't write those poems the same way now. But I had to respect who I had been when I was 57, 58, 59. So I just had to go, yeah, OK, I'm not going to rewrite that. I'm just going to let it stand. So, in a way, it's sort of life's summation at the age of 60. Also, it's everything significant that I could remember at the age of 60, being somewhat paranoid that by 65 I wouldn't be able to remember anything.

JM: When you get to the actual South China Sea section of the book, it's about travel, and there's a real change there. It moves into the present tense again. Want to talk about that present tense and travel?

KN: Sure, sure. This is the way the book is an autobiography, and it isn't an autobiography. On a certain level, it's just my latest book of poetry. It starts off as this memory project, but while I'm writing the book, I'm also starting to travel in China, and I'm finding the traveling quite compelling. So rather than talking about the past, I want to start talking about what's happening to me in the present. So, yeah, I would say the first half of the book is retrospective. And then suddenly it kind of shifts gears into: Here we are in China. Ok, let's go to Shanghai. Ok, let's go to Xining out in western China. And the past fades and the present becomes the foreground. So it's kind of kooky in that way: the first half of the book is retrospective and then the second half of the book is mostly about here and now. Or a lot of second half.

JM: But then you get to the Tao section and it comes back to memory again. How is it different from the first half?

KN: Well, I think one of the things I did at a certain point in time is I just did a poem count. You know, like in the first four sections of the book, there are between 10 and 20 memory poems in each section. When you get to the second half of the book, there are three or four. So it's just structured differently.

JM: The chapbook Hawaiian Sunrise is clearly a 2021 book. We're in the pandemic age with that book, right?

KN: Yeah, there's a Canadian poet named Justin Million who's actually writing a review of what he calls the Ken Norris Pandemic Trilogy. And Hawaiian Sunrise is the first one of the three. It was written in Hawaii in December 2020 and January 2021. And it's definitely pandemic influenced.

JM: You and I have both had a lifelong fascination with Melville and, in particular, "The Confidence Man". In this book, you conflate Melville's take on fraud and the tropics. Is there a connection for you between the Hawaiian environment and fraud or fakes?

KN: Oh, sure. Hawaii's the end of America, right? I mean, you go there and there are people pretending to be people they're not. And there are street people. You can't escape the homeless, even in Honolulu. But Melville, you know, is like us. Melville was a New York City guy. When he got some money, he moved to the Berkshires, but when he ran out of money, he went back to New York. So he's a New York City guy who wandered around the tropics, and I'm in New York City guy who wandered around the tropics too. So I feel a very strong connection with him there. And “The Confidence Man”-- I've been trying to write something about “The Confidence Man” for 30 years. And then finally, I wrote the poem "Catfishing in America". And one of the reasons I wrote it was because the pub date of "South China Sea" was supposed to be my birthday, April 3rd, and instead they moved it to April 1st. April 1st was the pub date for "The Confidence Man". And it's also a book that takes place on April Fools’ Day.

JM: I didn't know that. That was always a book that intrigued me, probably because I was never quite sure where Melville was going with it. And I think that was his whole purpose.

KN: Yeah, on a certain level, he's kind of presenting the idea that all of existence is a confidence trick and maybe God is the ultimate confidence man. You know, requiring our faith. And maybe shafting us in the process,

JM: Taking us for suckers for being faithful, right?

The Stray Dog Cafe is quite different than the other books. You're echoing Akhmatova -- you took the title from her. But you're also echoing Nazim Hikmet and Yeats as well. What was going on here?

KN: That's a really good question. Stray Dog Cafe is a chapbook that kind of fell out of a full-length manuscript. I was working on a manuscript called "Living in the Masterpiece", and I was working to a deadline, because now Canadian publishers have reading periods. This publisher--the last date to submit was the 30th of the month, and it was the 25th, and I was still typing, trying to get this manuscript done. So I had to cut corners, and what was left behind in my notebooks was what became “Stray Dog Café”. It was like 30 poems that didn't make this full-length manuscript. That being said, a lot of the poems in there seem to be about poets and poetry. The Stray Dog Cafe was an actual cafe that Akhmatova and Mandelstam and Pasternak used to hang out in in St Petersburg around 1912 to 1915. Louis Dudek had a poem about stray cats. I think it's called “The Stray Cats”, but it's really about poets. The Russians considered poets to be stray dogs, and Dudek was considering poets to be stray cats. So I just picked up on the whole idea of strays. With these stray poems that I had.

JM: I see a strong theme running through all three of those poets. Akhmatova, Hikmet, Yeats all struggled with coming to terms with personal death in very different ways. Akhmatova was pretty much just resigned to it. It was part of what was going to happen to her. With Hikmet, you echo his "Things I Didn't Know I Loved." He wrote about what it is to be alive. And Yeats struggles with what comes after, what can I look forward to. Was that a conscious theme on your part? Trying to come to terms with what the end of life is?

KN: Yeah, I think it's more coming to terms, right? At certain point, you realize you're talking about something. When we were younger, back at Stony Brook, you were really into Williams and I was really into Yeats. And even at the age of 20, I was interested in how Yeats was trying to process old age. And he's really kind of interesting -- he's kind of weirdly interesting with Byzantium and stuff like that. Yeats was operating on all cylinders as an old poet, which isn't necessarily what happens with all old poets. So South China Sea I finished when I was 60; "Living in the Masterpiece" I probably finished writing that when I was about 67. I was getting older, and I was thinking about aging and being an older poet and what that's all about really. But rather than working it as a theme, it was just what I was thinking about.

JM: Well, what did you take from Hikmet, who's always been one of my favorite poets but who doesn't really get read much in English?

KN: I haven't read a lot of him, but I my understanding of "Things I Didn't Know I Loved" is he wrote it when he was in prison. He had this time to reflect upon all the things in life he experienced when he had freedom now that he was unfree.

JM: And for him the way to be alive is to defy death.

KN: One of the things you can do when you get older is take inventory.

JM: So the next manuscript you're working on, is it going to continue this taking inventory?

KN: I'm not working on anything now, but I completed two manuscripts that are out at out publishers. One of them is "Living in the Masterpiece". And what's the other one? Oh, "Three Winters."

Yeah, "Three Winters" is a manuscript that really interests me. It's three winters that I set out to spend in Asia. The first winter I wrote a section that I also turned it into a chapbook called Hong Kong Blues. I was in Hong Kong, and it was before the pandemic and before the Chinese government came down hard on the democracy movement in Hong Kong. So I was just in Hong Kong taking inventory. The second winter is when everything went tits up in Hong Kong. And students were demonstrating, and the Chinese government decided to crack down hard on Hong Kong. It was like OK, forget this allowing you to have certain freedoms until 2047. That ends today. And then the third winter is the pandemic. One section is called "Hawaiian Sunrise" and another section is called "Cultural Marginalia". I just wanted to spend three winters in Asia away from the Canadian winter, and all sorts of shit kept breaking loose. So it's three awfully interesting winters.

“Living in the Masterpiece” was written before “Three Winters”. It was written in calmer times. When I was editing it, I was worried that the quieter times were going to maybe disqualify it, but I think it turned out pretty well. It's off with a publisher now.

I would say it's more meditative than “Three Winters”. “Three Winters” keeps having to adjust to "current events." “Living in the Masterpiece” is just trying to get comfortable inside existence, as the title kind of indicates. Why struggle so much when we are, in fact, living in the masterpiece?

JM: So those two are finished. What comes next?

KN: Right now, I don't know if there are going to be any books after “Living in the Masterpiece” and “Three Winters”. I didn't write any new poems for almost all of 2021. My hero Phyllis Webb said that poetry "abandoned her" when she was around 60. I'm 70 now and wondering if poetry is in the process of abandoning me now.

I have a secret project planned for when I'm 80. So there will be more work published, even if I don't write any more poetry. I think the jury's out on that one right now.

Ken Norris was born in New York City in 1951. He came to Canada in the early 1970s, to escape Nixon-era America and to pursue his graduate education. He completed an M.A. at Concordia University and a Ph.D. in Canadian Literature at McGill University. He became a Canadian citizen in 1985. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of Maine, where he taught Canadian Literature and Creative Writing for thirty-three years. He currently resides in Toronto.

Jim Mele is a journalist and writer living in Connecticut. He was co-editor of CrossCountry, a Canadian/US literary magazine and publisher, and also served as general manager of the New York State Small Press Assn., a non-profit created to distribute literary and artistic publications. He has traveled broadly both as a journalist and as a curious private citizen. His journalism has been recognized with numerous awards including three Neal Awards for op-ed commentary, and has published four collections of poetry and a critical study of Isaac Asimov’s science fiction. He holds a BA in English from Stony Brook University and an MA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York.