Mushrooms Yearly Planner, Jen Tynes

above/ground

press, 2021

What a pleasant surprise to open Tynes’ poetry chapbook and not be barraged by the usual over-wrought, bitterly sensitive, deeply personal, highly emotional, deathly serious, self-righteous fare, chock full of the habitual platitudes, philosophical clichés, stock phrases, tired images and…but wait, enough about me, and my own rather pathetic poetic shortcomings, I wanted to talk about the flip side of what a poem can be; wherein an innocent reader might meander gently (somewhat freely) through a landscape that is both recognizable and remarkable, as well as be allowed to engage (or not) with the process, even be confounded, at times, lost, without the constant pressure of the all-knowing poet yammering in their ear so as not to miss the intended destination.

Now, I’m the type who tends to zip through a first reading of a collection of poems and let whatever happens happen. If I’m positively disposed and/or entertained in some fashion, I read to the end, if not, I chuck the fetish object unfinished into the recycle bin or put it into a box destined for the local used book store. Flaubert said: Anything becomes interesting if you look at it long enough. Sorry, Gustave, I tend to disagree. Life is way too short.

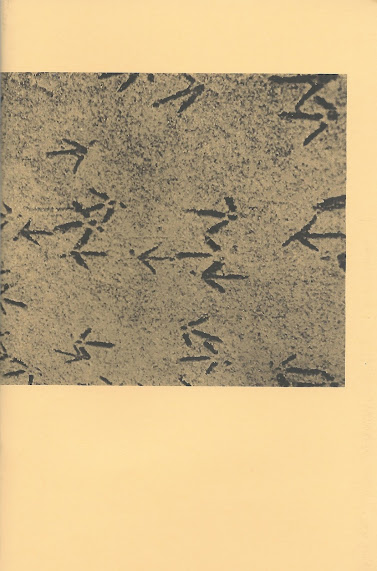

What struck me fairly quickly? The general avoidance of similes — “a bird that comes down all too easily” sd Charles Olson — and the reliance on common objects and situations placed in odd juxtaposition in order to create an almost surreal narrative landscape: “Sex takes a little while // to get interesting, polishing its fenders and leaving pets to howl / in the brown grass.” To carry this notion of “common” or “commonality” even further, Tynes essentially blurs the distinction between flora and fauna, animate and inanimate, human and object (“I have lost / my sharp markings, their articulation”). In fact, these classifications are in constant flux and transformation: “… the man at the visitor’s / information kiosk flowers just once // a century,” and: “A mattress that crystallized. / Birds bursting into pea gravel.” In this way, Tynes manufactures a universe where each entity is given equal weight and importance: fully alive, implicated and impactful, one thing acting continuously/contiguously wham! upon another.

Having reached the end of the chapbook, it (by some unknown means) occurred to me that I wasn’t sure if I’d experienced one long poem or several shorter poems. It appeared that the texts were limited to one per page (there was one page filled top-to-bottom by a text and it seemed to bleed over easily into the following text, which could have been coincidence, or)…so possibly individual poems, yet there were no titles to further indicate that this was the case. I referred to the back credits’ page where it said that some of these “poems” had originally been published in magazines, ergo, a collection of poems, not one long poem, yes? I wondered: did it matter to me one way or the other? Did it alter my reading of the book? My interpretation? But, what interpretation? I had simply enjoyed the poems for their formal intrinsic value and — while I had picked up on certain thematic elements — I wasn’t at all positive that I’d walked away with anything definitive in terms of a specific subject matter. It was then that I recalled the title: “Mushrooms Yearly Planner.” What goddamn mushrooms? I asked myself. I don’t remember reading anything about mushrooms in the book, never mind a Mushrooms Yearly Planner, for that matter. Nothing. Nada. I went back to the beginning to see if I could discover any clues.

In the second line of the opening poem, Tynes writes: “This is a forensic poem.” The word “forensic” having to do with scientific tests or techniques used in connection with the detection of crime. Hm, intriguing. And, sure enough (reading further), the text contains many examples surrounding these procedures: “A deer is captured chewing / on a human bone,” and: “Blue flowers the size of fingernail clippings / have names.” Tynes asks: “What is a discovery / even doing in this neighbourhood?” A question often asked by citizens when crimes are committed in their quiet boroughs. They can hardly believe, yet, crime, even violent crime, respects no boundaries. “We power wash // spider mites and get talked to / by the police. Longest day // of the year and the gun / still in its holster.”

We get hints, though nothing specific, as to the exact nature of the crime. Beyond this, there still remains no mention of the word “mushrooms” to be discovered anywhere in the text(s). Then I realize, I also have absolutely no idea what a Mushrooms Daily Planner is, or if such an animal exists. I Google and find that it’s a sort of calendar which is “perfect for jotting down your wonderful ideas or aspirations, tracking down your fitness program, keeping your good recipes, and documenting other accomplishments.” Makes sense, as Tynes seems more interested in the physical accumulation of data in its myriad guises and in its presentation to an audience for them to mull over and decipher, to “crack the case” as it were: “I record better on days / I have pockets.” Yes, because pockets provide a tangible location where she can stash notes and found materials to take home and have available in order to construct her poems. And what splendid turns of phrases here: “I check the slides // for feces before the kids show up. / I examine beautiful names // for things that are ordinary.” The “slides” (at first glance) can be regarded as glass plates containing fecal evidence to be put under a microscope for examination, but then effortlessly transforms into something more chillingly real: children’s playground slides which may be contaminated by feces — what? how? by whom? for what no-good purpose? No explanation is offered. And feces? A beautiful name, yes or no? Well, sure, why not? Beauty being in the eye of the beholder, and so on and so forth, “For things that are ordinary.”

Meanwhile, I don’t miss the fact that mushrooms are grown in shit (nutrient-rich compost) and also have beautiful names: bisporus brunnescens, matsutake, chanterelle… Or that the chapbook itself is the Mushrooms Daily Planner, with its display of raw materials, gathered, recorded and arranged in a particular order by the poet.

The final poem begins: “So ritual dagger and turning gold back / to straw.” The endless process/cycle/ritual of death and renewal. The completion of one yearly planner and the beginning of the next. Digging through the shit to uncover the beautiful.

Of course, I could be totally wrong in my interpretation, and that’s fine with me, pleased to be permitted to wallow in the text without benefit of a defining road-map, the journey being every bit — more! — as interesting as the arrival. And as for Flaubert, I will concede that anything already interesting become more interesting if you look at it long enough. And, it’s true, Tynes’ chapbook continues to fascinate with multiple readings. To pick up and run with a quote from Tynes: “I tie the knots. Nothing blows away.”

Stan Rogal lives in the The Big Smoke, not to be confused with the recently opened cannabis outlet at the corner of Dovercourt and Bloor, which he frequents for research purposes only. The author of several impossible-to-locate books; published in various magazines and anthologies scattered like wacky-tabacky ash across the country. A Spinozian pantheist and former porn star.