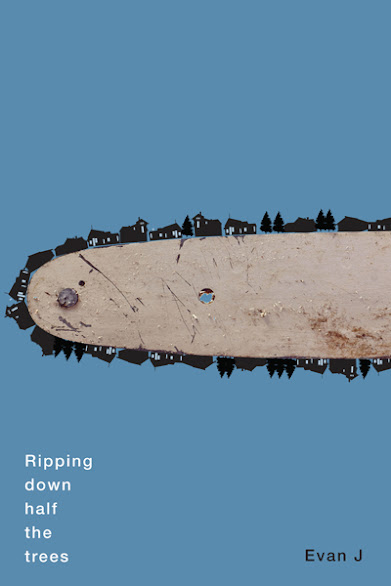

Ripping down half the trees, Evan J.

McGill-Queens Press, 2021

Evan J’s debut collection, Ripping down half the trees, is one that travels from Southern Ontario, to Manitoba, and then even further north to Thunder Bay and Sioux Lookout, where the poet now lives and works in the field of adult education. In the very first poem in the book, “Bloor-Yonge,” Evan writes of Toronto, of “the blank passive everyones” who are “maddened to escalator” while the “full-timer subway hustlers” consistently and plaintively ask passersby for help. Later, in poems like “If Homelessness if a Sandwich, Our Culture of Silence is the Bread” and “Note to the People Using Old Needles Stolen from a Public Bathroom,” the poet is acting as a witness to the life that teems around him, pointing out the racial and social inequality that continues to exist across Canada.

Evan situates himself as a white cis-man, settler, and teacher by being sure that his readers are clearly aware that he very much knows what it is that he carries with him to these new places in which he lives and writes. In “Beyond Ear But Open,” he writes, honestly: “I am boy, your jeering tongue dubbing me/Evan Almighty because I appear weekly/with all the whitest toys for learning.” In the brilliant poem, “Colonialism for Dummies,” Evan speaks to other settlers who might make excuses for their ancestors’ historic colonization of this country: “You can call your ancestor’s passage an invasion, I mean/an exodus, a historic flight from poverty or famine or/communist murder.” He continues to write “…be sure to vocalize your distance from the violent and oppressive acts” until it is easy enough to justify shooting “a Cree man in the head, I mean murder, and go/unpunished.” What the poet is doing, throughout so many of the poems gathered in Ripping down half the trees, is drawing attention to the settler tendency to explain away systemic racism that has been rooted in Canadian history for hundreds of years. He holds a mirror up so that the reader needs to look inwards to their own sense of privilege, as well as outwards towards the poetry.

Structurally, there is a powerful series of “How to” poems that are woven throughout the collection. In “How to Clean Walleye,” Evan begins with his tongue in cheek: “Use soap. Just kidding. Use a boulder waist-high as a/butcher table. Lay the fish sidelong, backbone across your/belly.” In “How to Stay Alive on the Streets of Sioux Lookout,” Evan’s tone shifts as he writes: “Keep a distance from most white folx./Finish dirty jokes in Oji-Cree./Keep your feet moving when the OPP patrol./The Kenora Jail is worse than cold or hunger.” Further on in the book, in “How to Fly Home,” the poet writes of a homeless man in Northwestern Ontario whose name is Mike and who “is a survivor, and if lucky/around midnight he will sleep rough and alive beneath a/totem of capital failures, a hungry homeless head on cement/just inches from banknote pillars, the pillows of green queens.” As a reader, you simply cannot turn away. In some cases, you may only be able to bear reading one or two poems at one time, just because the pain can feel that palpable and tangible—something which speaks to Evan J’s skill at recording very difficult things in his poems.

If you’re from the north, or you’re familiar with small northern towns, you’ll know that they aren’t simple things. They have histories that stretch back in time, and usually revolve around resource extraction. Some of these places are the mining and mill towns, and the tiny places marked on folded CAA paper maps that used to live in the glove boxes of family cars. When you read Ripping down half the trees, if you’re a northerner, you’ll feel the harsh truth of it all, recognizing the stories of people who you’ve likely seen on your own hometown’s streets—knowing that colonialism, social inequality, and systemic racism haven’t disappeared, but have only rooted down more stubbornly into the earth. Through Evan J’s poems, these social injustices are highlighted, opening spaces where important conversations need to be taking place.

Kim Fahner lives and writes in Sudbury, Ontario. She was poet laureate in Sudbury from 2016-18, and was the first woman appointed to the role. Kim's latest book of poems is These Wings (Pedlar Press, 2019). She's a member of the League of Canadian Poets, the Ontario representative of The Writers' Union of Canada (2020-22), and a supporting member of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. Kim can be reached via her author website at www.kimfahner.com